CHARLES JOHN NOKE FOR ROYAL DOULTON, DESPAIR 'The Old Woman' (formerly known as Despair), a very rare figure decorated in flambé and Sung glaze, c.1913Note: Very few examples known, similar figure noted on page 165 of 'The Royal Doulton Figures Book' by Eyles, Dennis and Irvine (Third Version)11cm high Overall, in good condition, with some small areas of age. In particular, there is a small area on the clasped hands which show slightly lighter in strong lighting, which can be seen in the first image. It is unclear whether this is a varation in the glaze, as it does not show any cracking or crazing.

We found 44718 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 44718 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

HERBERT THOMAS DICKSEE RE (BRITISH 1862 - 1942), ETCHING 'OH FOR THE TOUCH OF A VANISHED HAND' etching on paper, framed and behind glass, mounted with lighter wood to the frame, and adorned with a bone plaque stating 'OH FOR THE TOUCH OF A VANISHED HAND', relating to the forlorn expression of the Irish Wolfhound, clutching a much loved owner's glove50cm x 82cm Overall, good condition for the age of the lot. A good amount of surface dust etc to the frame and glass. Bone plaque in good conditon, and framing appears to be sound.

A group of clear glass items, to include a Vera Wang for Wedgwood cut glass spherical bowl, height 10.5cm, a cut glass footed bowl with etched glass cartouche, signed 'Wettiuger' and numbered 072/109 to the edges of the cartouche, height 18.7cm, a large oval glass bowl, handled drinking glasses, decanter stoppers, also a paperweight in the form of a teapot and a Colibri white glass table lighter.

A quantity of plated ware, to include teapots, cocktail shakers, a cruet set on stand, a toast rack, jugs, a ceramic cruet set on a plated stand, etc, also a table lighter in the form of a muzzle-loading pistol, two cased sets of compasses/drawing implements, a ceramic pillbox with 'L'Arc de Triomphe' to the lid, etc.

A traditional lighter with a leather pocket and added metal and brass elements, with embossed, debossed decorations and a central turquoise. In the lower area, there is a thick metal plate, in the shape of an axe with angled edges, designed to be rubbed with a stone or other metal to generate sparks. Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) or later. Size: 7 x 2.2 x 13.5 cmWeight: 164 g

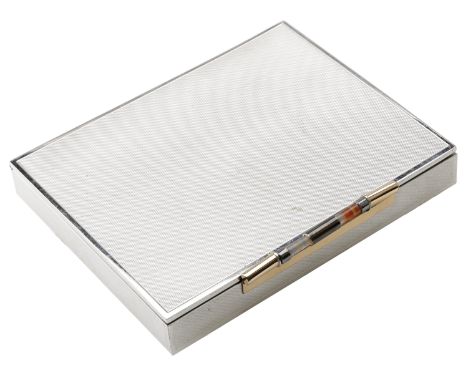

An Art Deco styptor and gold mounted minaudière by Van Cleef & Arpels, circa 1935, of rectangular form with engine-turned decoration throughout, and agate set sprung thumbpiece, the fitted interior with mirrored lid, and containing compartments for lipstick, powder, a lighter and an unassociated silver and gold inset square compact hallmarked for Birmingham 1948, signed ‘LA MINAUDIÈRE FOR VAN CLEEF & ARPELS’, and to the inner rim ‘SPECIALLY MADE FOR ASPREY’, stamped ‘STYPTOR’, with original Asprey black velvet and watered silk-lined slip case/handbag, dimensions 15.2 x 12.5cm. £500-£700 --- Condition Report Agate thumbpiece a replacement and solder evident - was likely originally diamond-set. Slight wear evident to the exterior. Comb present. Powder compact (unassociated) by Mappin and Webb.

A REGENCY ROSEWOOD AND UPHOLSTERED LIBRARY ARMCHAIR IN THE MANNER OF GILLOWS, CIRCA 1820 97cm high, 70cm wide, 67cm deep Condition Report: Overall there are some scratches, marks, chips, knocks and abrasions consistent with age and use.The upholstery is slightly lighter in reality that is suggested by the catalogue image. The upholstery is a slightly stiff tufted moquette/velvet, with later braiding and though intact it shows signs of wear and indented lines of the underlying frame. The frame under the upholstery and undercloth have not been inspected.A solid library armchair.Please see all the additional condition report photographs through the link on the condition report email as a visual reference of condition - they are a vital part of this report. Condition Report Disclaimer

A BEAUVAIS AMUSEMENTS CHAMPÊTRES TAPESTRY AFTER JEAN BAPTISTE OUDRY FRENCH, CIRCA 1780 Woven with Oudry's design 'La Main Chaude' ("Hot Cockles"), figures in a wooded landscape beside a stream and stone folly, an open landscape with chateau visible in the distance, a shepherdess and her flock on the opposite bank, within a scrolling bold acanthus frame border approximately 300cm high, 397cm wide The design for this tapestry panel belonged to a series of "amusements champêtres" devised by Oudry (1686-1755) with one stage of his composition preserved in a drawing in the Stockholm National Museum (No. 2890 / I863). The scene features a game of "hot cockles" where a blindfolded person bent over with his head in the lap of a woman. The other players slapped him on the hand that is tucked behind his back, and he had to guess who it is. When the person guesses correctly who slapped him, that person takes his place. The game is depicted in a contemporary painting (1767-1773) by Fragonard (National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1946.7.6). A version of this tapestry is held in the Harvard Art Museum (1953.114). Condition Report: With wear, marks, repairs and sun fading as per age, handling, use, and cleaning. The whole with a slightly brown tint but retaining some of the more fragile lighter colour tones. Numerous areas of stitch repairs- but with some fragility resulting in some open areas with backing visible. Backing fairly modern. May benefit from remedial conservation prior to installation in domestic setting. Please see additional images for visual references to condition which form part of this condition report. All lots are available for inspection and Condition Reports are available on request. However, all lots are of an age and type which means that they may not be in perfect condition and should be viewed by prospective bidders; please refer to Condition 6 of the Conditions of Business for Buyers. This is particularly true for garden related items. All lots are offered for sale "as viewed" and subject to the applicable Conditions of Business for Buyer's condition, which are set out in the sale catalogue and are available on request. Potential buyers should note that condition reports are matters of opinion only, they are non-exhaustive and based solely on what can be seen to the naked eye unless otherwise specified by the cataloguer. We must advise you that we are not professional restorers or conservators and we do not provide any guarantee or warranty as to a lot's condition. Accordingly, it is recommended that prospective buyers inspect lots or have their advisors do so and satisfy themselves as to condition and accuracy of description. If you have physically viewed an item for which you request a report, the condition report cannot be a reason for cancelling a sale. Buyers are reminded that liability for loss and damage transfers to the buyer from the fall of the hammer. Whilst the majority of lots will remain in their location until collected, we can accept no responsibility for any damage which may occur, even in the event of Dreweatts staff assisting carriers during collection.Condition Report Disclaimer

A PAIR OF ITALIAN BLUE AND WHITE PAINTED ARMCHAIRS VENETIAN, MID 18TH CENTURY Upholstered in ochre velvet minor difference in height, the tallest 101cm high, 73cm wide, 56cm deep Condition Report: Overall there are some scratches, marks, chips, cracks and abrasions consistent with age and use.Observations include: the colour slightly lighter somehow than the catalogue images suggest; later painted with a distressed finish; the upholstery with signs of age and wear; some loose joints and some repair to these areas, itis difficult to discern under the layers of paint the extent of any repairs and later wood etc; there is evidence of old worm; some later blocking to the corners of the seat rails.A decorative pair of appealing armchairs.Please see all the additional condition report photographs through the link on the condition report email as a visual reference of condition - they are a vital part of this report. Condition Report Disclaimer

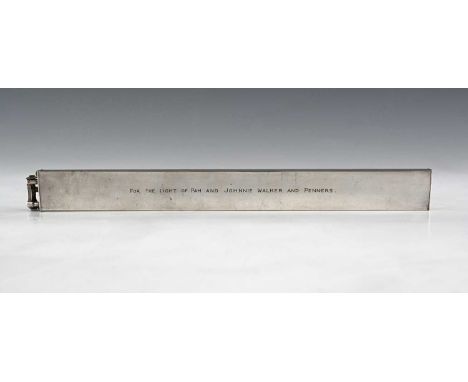

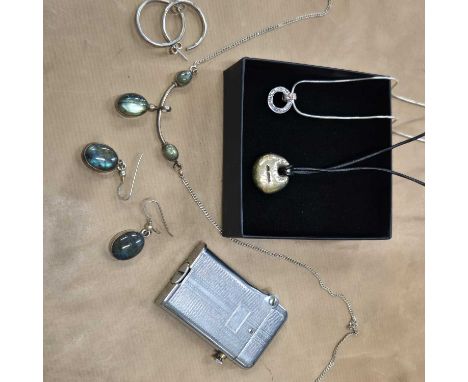

Social and Grand Tour Interest - an Art Deco Mappin purse clock, 17 jewel movement, leather case, 8cm wide fully extended; a Dunhill rolled gold and machined cigarette lighter, cased; a Victorian passport, Mary Elizabeth Twigg, dated 1887; an associated lady’s cigarette wallet, notebook, Japanese miniature musical box, etc (qty)

A near pair of 19th century Anglo Indian Padouk wood snap top occasional tables, each with carved edge and frieze, turned centre column and tri-form base raised on short bun feet. Height both 76 cm, darker table top width 52 cm, lighter table top 51 cm, size across the base varies slightly (see illustration).Both tables are structurally sound and in good order. They show signs of age-related wear but nothing untoward.

Dunhill Joseph Lucas table lighter, marked to top Dunhill and engraved to side "To JL from JL" and to underside "Plastic and styling by Joseph Lucas Ltd Birmingham England. Height 8.5 cm, width 10 cm (see illustration).The lighter appears to be all present. The flip wick exposer mechanism operates as it should and the flint wheel rotates as it should. The metalwork is all very dirty and has lost some of the surface finish. The plastic surround is free from any splits or cracks but does have numerous surface scratches as one would expect.

A George V four piece silver tea set. Thomas Bradbury & Sons, London and Sheffield, 1917. The set comprising a teapot, coffee pot, sugar bowl and milk jug, all of oval form and raised on rectangular bases, the coffee pot with ebonised wooden handle, the wooden teapot handle of a lighter colour, coffee pot 27cm high, teapot 18cm high (inc .handles), total weight approx. 53.6ozt (4)

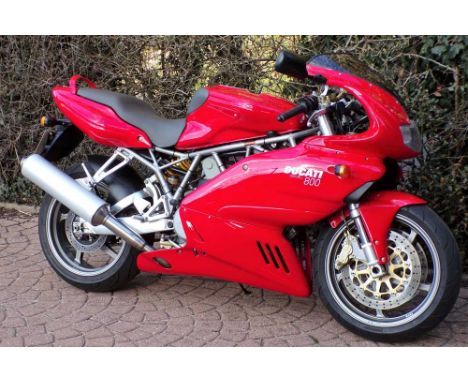

Registration No: P90 OSL Frame No: 023455 MOT: February 2026No.58 of the Mk5 limited edition Superlight 900Speedo shows a credible 6,231 miles from newSupplied with receipts, manual, 2 keys and a V5CDucati was established in 1926 by Antonnio Ducati and his sons, initially producing electrical components. After WW2 they moved into motorcycles with the Cucciola, essentially a pushbike with a clip-on engine. By the 60s they had become associated with performance bikes selling a range of sporty 250 and 350 singles. In response to the demand for larger capacity bikes, Ducati's chief engineer Fabio Taglioni designed the classic V-twin bevel drive engine first used in the 1971 GT750. An immediate success, helped considerably by Paul Smart’s win in the 1972 Imola 200 race, started a tradition of race-winning V-twins that have gone on to dominate World Superbike racing over the years. The SS range of air-cooled twins in various capacities offered a simpler alternative to Ducati's more expensive 8-valve Superbikes with the ultimate version being the 900 Superlight. This limited edition model had a dry weight of just 381lbs making it lighter than some 250s. This rare and collectible 900SL is a Mk5 model, the last of the Superlight range incorporating all the upgrades developed over the preceding years. The plaque on the top yoke shows it as being number 58 of the limited edition run of Mark 5 bikes manufactured in 1996. Presenting to an excellent standard in unrestored and original condition, the speedo shows just a credible 6,231 miles. Owned by the vendor for the last 10 years, he has kept it maintained and is currently MOT'd until February 2026 and it will come supplied with an owner's manual, various receipts and both keys together with current V5C. Very fittingly, the registration number could be perceived to be 'P 90O SL' and complements the bike perfectly. For more information, please contact: Ian Cunningham ian.cunningham@handh.co.uk 07415871189

Registration No: 435 UXL Frame No: TF24433 MOT: ExemptEarly post-war panel tank modelTele front forks, rigid rear suspensionFinished in classic Amaranth RedTriumph is one of the most iconic and revered names in the history of motorcycling. Established in Coventry in 1885, by the start of the 1900s the company had made their first motorcycle beginning a continuous run of production under various ownership until its eventual closure in 1983. In 1937 the Edward Turner designed Speed Twin was released launching a range of Triumph twins that went on to epitomise British motorcycles in the post-war years. The 500cc OHV twin was a major turning point for the British motorcycle industry being lighter than many contemporary singles with significantly more power and torque, prompting most other manufacturers to follow suit with similar models. The basic layout survived in various engine sizes up to 750cc until the eventual closure of the factory in the early 1970s. Triumph staged a remarkable comeback in the 1990s with a range of completely new machines based on the spirit of bikes like the original Speed Twin. This beautifully presented Speed Twin, finished in distinctive 'Amaranth Red', is an early post-war model with the gauges set in a panel in the fuel tank like the pre-war models but with telescopic front forks, fitted once Triumph resumed production after WW2 in 1947. Restored keeping a good degree of originality, including a period style tyre pump and the panel lamp that is usually missing, it was bought by the vendor about 20 years ago and has only been ridden sparingly since. It is offered with a current V5C and a parts manual. Dry stored in recent years, it will need recommissioning before use. For more information, please contact: Ian Cunningham ian.cunningham@handh.co.uk 07415 871189

Registration No: VBW 760 Frame No: DH16495W MOT: ExemptGood looking Cruiser 89 twin-cylinder 250Authentically restored in Green and CreamSupplied with its original RF60 and a V5CFrancis & Barnett Limited was an English motorcycle manufacturer founded in 1919 by Gordon Inglesby Francis and Arthur Barnett and based in Coventry. Early motorcycles were affectionately known as 'Franny Bs' and were produced for enthusiasts and as affordable bikes for use as general transport. The majority of the lighter motorcycles used Villiers two-stroke engines with the later bigger capacity models using Associated Motor Cycles engines. AMC took over Francis & Barnett Limited in 1947 merging with the James motorcycle company in 1957, remaining in business until 1966. This Francis Barnett Cruiser 89 twin, being offered at 'no reserve', is part of a deceased estate having been owned and ridden by its enthusiast owner over the last 15 years. As a lifelong motorcyclist, he maintained and rode all of his collection in VJMC events, runs and rallies. Francis Barnetts are a good introduction to classic motorcycling featuring a sturdy and simple to maintain chassis powered by tried and tested Villiers engines with a plentiful spares backup. Not run for a while due to ill health, it will require recommissioning and comes supplied with its original buff RF60 logbook together with a current V5C. A typography error on the V5C shows the frame number as 1649S instead of 16495 which is visibly stamped on the frame and recorded on the buff logbook. For more information, please contact: Ian Cunningham ian.cunningham@handh.co.uk 07415871189

Registration No: JBC 212V Frame No: 088794 MOT: ExemptA genuine family owned 900SS from newA mostly original Ducati that has been cared forAll original paintwork from newA current V5C on fileFollowing Paul Smart's success at the 1972 Imola 200 Formula 750 race aboard a brace of specially prepared desmodromic V-twin, there were demands from the public for a replica. Aside a limited run of homologation specials; fortunately, in 1975 Ducati introduced the 900SS, a machine that shared the same DNA whilst being built in greater numbers. It adopted the square case 860cc engine whilst retaining the 750SS cycle. The Silver and Blue livery worn by the first examples changed to a Black and Gold livery for 1978 which continued until 1980.This Ducati 900SS was purchased on 6th February 1980 from Apple Motorcycles in Hinckley, the original sales receipt is in the comprehensive document folder supplied with the bike. It has had only two owners and has been in the same family since new, ridden regularly during the early 1980s, including trips to the Isle of Man and to Grand Prix events in Germany and Holland. The GB sticker is still present on the original dual seat which will be included in the sale, the single seat was fitted in 2020. In the mid-1980s, the bike was put away in storage, however, it was kept clean and the engine turned over at various intervals. 2015 saw the bike sold to another family member who recommissioned the machine with full overhauls of the front and rear Brembo brakes, including new Hel Performance brake lines and the Dellorto carburettors which were also comprehensively rebuilt with many new internals, including floats and accelerator pump diaphragms purchased from Eurocarb Ltd. As part of the recommissioning process, the original-fit Speedline Gold magnesium wheels were replaced with stainless spoked wheels. The original magnesium wheels will be supplied with the bike along with the original plastic bellmouths and indicators. The clutch action has been improved by the addition of the longer clutch action arm, giving a much lighter easier pull at the clutch lever. The engine has never been apart, and the factory lead seal is still present on the front cylinder exhaust locking ring. The paint, decals and fairing/screen are all original with no respraying or replacements. The bike will be supplied with a comprehensive set of paperwork including the original purchase documentation, previous MOT certificates, a quantity of purchase receipts for service items, replacement parts including the spoked wheels etc and some related Ducati paperwork. Also included are the rare Ducati factory service books, the owner’s manual and original warranty documentation. The Ducati has been ridden regularly each summer (dry miles) since 2015 and was last ridden in the summer of 2024. For more information, please contact: Mike Davis mike.davis@handh.co.uk 07718 584217

Registration No: 657 BPX Frame No: BBC15495 MOT: ExemptGood looking Cruiser 80 single-cylinder 250Authentically restored in classic Arden GreenSupplied with a current V5CFrancis & Barnett Limited was an English motorcycle manufacturer founded in 1919 by Gordon Inglesby Francis and Arthur Barnett and based in Coventry. Early motorcycles were affectionately known as 'Franny Bs' and were produced for enthusiasts and as affordable bikes for use as general transport. The majority of the lighter motorcycles used Villiers two-stroke engines with the later bigger capacity models using Associated Motor Cycles engines. AMC took over Francis & Barnett Limited in 1947 merging with the James motorcycle company in 1957, and remained in business until 1966. This Francis Barnett Cruiser 80 single, being offered with 'no reserve', is part of a deceased estate having been part of the vendor's collection of mainly British bikes. As a lifelong motorcyclist, he maintained and rode all of his bikes in VJMC events, runs and rallies. Francis Barnetts are a good introduction to classic motorcycling featuring a sturdy and simple to maintain design with an easy to work on two-stroke engine. Not run for a while due to ill health, it will need recommissioning and comes supplied with a current V5C. Please note: The frame number listed has been taken from the V5C as it is not clearly visible under a thick layer of paint. There's also an engine number typography error on the V5C; it shows as 197CH instead of 19764 as stamped on the crankcases. For more information, please contact: Ian Cunningham ian.cunningham@handh.co.uk 07415871189

Registration No: S800 DCT Frame No: ZDMV500AA3B002387 MOT: August 2025Just one owner from newMeticulously maintained and looked afterNever been out in the rainAll paperwork from newCurrent V5C on offerDucati's Supersport featured premium components, including adjustable USD front and rear mono-shock suspension, the lighter and stronger alloy swing-arm from the 1000cc model and lightweight 5-spoke Marchesini wheels. The Supersport variant of the SS800 was discontinued in 2004, reportedly due to its price overlapping with the 1000cc model leaving only the SS800 Sport in the range. The SS800 always saw greater sales in the United States, where it became a popular choice for racing, achieving notable success in the Twins Cup series. On offer is a rare SS800 Supersport model in immaculate, original condition. With only one owner from new, it was first registered in 2008 after being unpacked from its original Ducati shipping crate. It has been meticulously maintained as a second bike, with full MOT and service records verifying its low mileage—just 15,112 miles. Also included, are original keys (including the red key), a toolkit and manuals in the under-seat pouch. The last service was completed in August 2024, with only 21 miles covered since. A private plate 'S800 DCT' is included. According to DVLA records, only ten SS800s (Sport and Supersport) remain on UK roads, making this Supersport version an exceptionally rare bike. Don’t miss this opportunity to own a true Ducati classic! For more information, please contact: Mike Davis mike.davis@handh.co.uk 07718 584217

Registration No: 522 UYW Frame No: 74135289 MOT: ExemptOlder restoration of a desirable IndianStill retaining its left-hand throttlePart of a collection of machinesUK registered with V5CThe Indian 741 was designed in 1939 to be used mainly for the US army and the armies of its allies. The 741 had a flathead V-twin based upon the civilian Thirty-Fifty model and was mainly used by couriers and scouts due to its lack of performance, but was very durable. A hand-change three-speed transmission with a foot-operated clutch was a typical practice for the day. The configuration is very similar to its bigger brother, the 750cc Military Scout (model 640B), however, the 500 was built lighter as regards to both frame and engine, there are also many differences in detail. The 741 production ran for about 6 years, until 1944, with about 35,000 machines being made. This wonderful 1942 Indian 741 was purchased by the current vendor for his collection of machines in 2020. The Indian was restored by a previous owner and its paintwork has mellowed very well. The 741 still retains its left-hand throttle, as per manufacturer specification. Since in the current ownership, it has been run occasionally however would benefit from the usual checks before putting it back on the road. This desirable Indian is offered with a current V5C on file. For more information, please contact: Mike Davis mike.davis@handh.co.uk 07718 584217

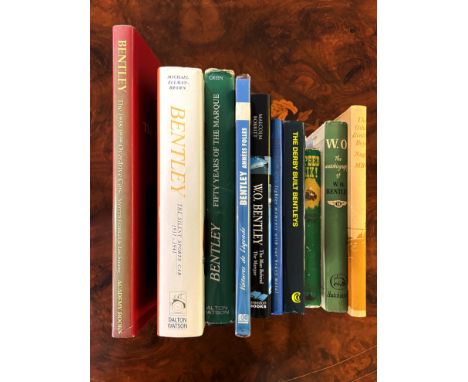

Green, Johnnie, Bentley, Fifty Years of the Marque,, pub. Dalton Watson, London, 1969, dust jacket; Malcolm Bobbitt, WO Bentley, The Man Behind the Marque, pub. Breedon Books Pub Co Ltd, 2003, dust jacket; Bernard L King, The Derby Built Bentleys, 2nd edition, complete classics 2012; Johnnie Winther, Bentley Lighter Moments with our Heavy Metal, pub. No 2 , 2001, WO Bentley Memorial Foundation; Elizabeth Nagle, The Other Bentley Boys Motoraces Book Club , pub. George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, London 1967, dust jacket; WO Bentley, WO An Autobiography, pub. Hutchinson, 1958, dust jacket; Bruce Carter, Speed Six, pub. Camelot Press, 1953, dust jacket; Richard Bird, Bentley Annees Folles, pub. Editions Atlas, 1992; Michael Ellman-Brown, Bentley- The Silent Sports Car 1931-1941, pub. Dalton Watson 1989, dust jacket; Mervyn Franklin & Ian Strang, Bentley The 1938/1939 Overdrive Cars, signed by the authors, pub. Academy Books 1994, dust jacket. (10)

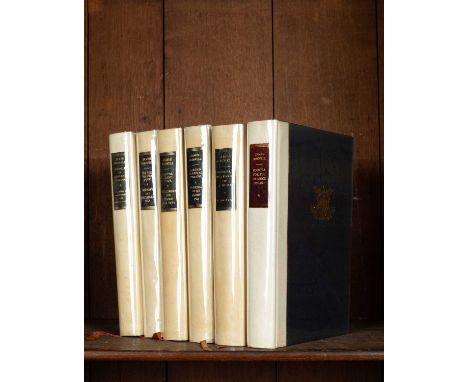

Boswell (James) The Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell, London, William Heinemann, 1951-1960, 4to, blue cloth and vellum spine with pasted morocco title labels; each copy hand-numbered or noted out of series (6)Purchased Sotheran’s, 1999Bindings generally in good condition with removable protective wrappers, back cover of volume 'On the Grand Tour ...' with horizontal scuff and some light wear. Some title labels a little cloudy. Vellum spine of 'Boswell for the Defence' lighter than remaining volumes, a little spotting to endpapers, some pages uncut, Scattered foxing but pages generally crisp and bright, fold out maps good with some scattered foxing. Includes original loose leaf description from Sotheran's, not collated

Dunhill 'Unique' Art Deco silver and enamel lighter, W&G, London 1927, the blue enamel body painted with bird amongst reeds, stamped 'PAT. No. 143752, 4.5cm.Condition report:We confirm the height as 45mm. (Size A). REPAIRED - enamel chip, approx 8x5mm, which has been painted over/ ground out. The silver cap covering the wick mechanism has been slightly compressed and bent downwards.

Robert 'Mouseman' Thompson of Kilburn, a nest of three Arts & Crafts oak coffee tables, carved signature mice, width 60cm, depth 37cm, height 47cm. Condition report:Largest table; top a little worn and slightly darker than the other two, joints are good, only very slight movement, some minor water marks to legs and railsMiddle table; top has some ring marks and wear, slightly lighter than the other two, joints are good, some water marks to the legs and rails Small table; the top is slightly worn, joints are good, minor water marks to the legs and railsAdditional images have been uploaded to the lot page on our website for you to view.

A Regency brass strung mahogany card table with D shaped folding top and ormolu oak leaf and bead mounts, on ring turned stem with downswept legs, fitted brass caps and castors,92cm wide, 46cm deep, 76cm high Good restored condition, an even mid brown tone slightly lighter to the top, minor signs of old wear throughout.PLEASE NOTE:- Prospective buyers are strongly advised to examine personally any goods in which they are interested BEFORE the auction takes place. Whilst every care is taken in the accuracy of condition reports, Gorringes provide no other guarantee to the buyer other than in relation to forgeries. Many items are of an age or nature which precludes their being in perfect condition and some descriptions in the catalogue or given by way of condition report make reference to damage and/or restoration. We provide this information for guidance only and will not be held responsible for oversights concerning defects or restoration, nor does a reference to a particular defect imply the absence of any others. Prospective purchasers must accept these reports as genuine efforts by Gorringes or must take other steps to verify condition of lots. If you are unable to open the image file attached to this report, please let us know as soon as possible and we will re-send your images on a separate e-mail.

An early Victorian teak secretaire campaign chest with central drop front writing drawer flanked by two deep drawers over three further long drawers, on turned feet, 99cm wide, 45cm deep, 106cm high Overall of a light gingery brown tone, fair state of polish, numerous fine old scuffs and scratches throughout commensurate with age, the central drawer with probably the original leather skiver and light burr wood veneered drawer fronts, locks stamped Patent London but no key present, first long drawer down is of slightly lighter tone and has scratching to the front, no carrying handles to the sides and there do not appear to have ever been any, the right hand side heavily sunbleached, feet may be later additions.PLEASE NOTE:- Prospective buyers are strongly advised to examine personally any goods in which they are interested BEFORE the auction takes place. Whilst every care is taken in the accuracy of condition reports, Gorringes provide no other guarantee to the buyer other than in relation to forgeries. Many items are of an age or nature which precludes their being in perfect condition and some descriptions in the catalogue or given by way of condition report make reference to damage and/or restoration. We provide this information for guidance only and will not be held responsible for oversights concerning defects or restoration, nor does a reference to a particular defect imply the absence of any others. Prospective purchasers must accept these reports as genuine efforts by Gorringes or must take other steps to verify condition of lots. If you are unable to open the image file attached to this report, please let us know as soon as possible and we will re-send your images on a separate e-mail.

A Chippendale revival mahogany dining table and eight chairs, the chairs with elaborate scrolling splats, drop in seats and cabriole legs, the matching table with rounded ends and two leaves, extends to 238cm x 120cm, 73cm high, carvers 65cm wide, 102cm high Overall in good honest untouched condition, the suite is all of a very dark brown tone except for the top of the table which has a lighter gingery brown colour, some light surface scuffs and scratches to the top of the table, minor rubbing to the raised extremities of the chairs but overall good condition.PLEASE NOTE:- Prospective buyers are strongly advised to examine personally any goods in which they are interested BEFORE the auction takes place. Whilst every care is taken in the accuracy of condition reports, Gorringes provide no other guarantee to the buyer other than in relation to forgeries. Many items are of an age or nature which precludes their being in perfect condition and some descriptions in the catalogue or given by way of condition report make reference to damage and/or restoration. We provide this information for guidance only and will not be held responsible for oversights concerning defects or restoration, nor does a reference to a particular defect imply the absence of any others. Prospective purchasers must accept these reports as genuine efforts by Gorringes or must take other steps to verify condition of lots. If you are unable to open the image file attached to this report, please let us know as soon as possible and we will re-send your images on a separate e-mail.

A Liberty & Co. Arts & Crafts oak dwarf bookcase with raised pierced frieze and four leaded doors flanked by upper recesses on stile feet, 185cm wide, 25cm deep, 120cm high Honest untouched condition, a fairly dark brownish stain throughout which is slightly lighter from sun and wear to the front edges of the open shelves, the doors enclose eight adjustable shelves, copper handles and escutcheons look original and come with working keys.PLEASE NOTE:- Prospective buyers are strongly advised to examine personally any goods in which they are interested BEFORE the auction takes place. Whilst every care is taken in the accuracy of condition reports, Gorringes provide no other guarantee to the buyer other than in relation to forgeries. Many items are of an age or nature which precludes their being in perfect condition and some descriptions in the catalogue or given by way of condition report make reference to damage and/or restoration. We provide this information for guidance only and will not be held responsible for oversights concerning defects or restoration, nor does a reference to a particular defect imply the absence of any others. Prospective purchasers must accept these reports as genuine efforts by Gorringes or must take other steps to verify condition of lots. If you are unable to open the image file attached to this report, please let us know as soon as possible and we will re-send your images on a separate e-mail.

An early 19th century Dutch marquetry inlaid walnut display cabinet with two glazed doors enclosing shelves over two short and two long drawers, on scroll feet, 150cm wide, 40cm deep, 217cm high Looks to be in fair to good condition, an even gingerish tone which is slightly lighter across the drawers where they have bleached a little, original locks fitted with several working keys.PLEASE NOTE:- Prospective buyers are strongly advised to examine personally any goods in which they are interested BEFORE the auction takes place. Whilst every care is taken in the accuracy of condition reports, Gorringes provide no other guarantee to the buyer other than in relation to forgeries. Many items are of an age or nature which precludes their being in perfect condition and some descriptions in the catalogue or given by way of condition report make reference to damage and/or restoration. We provide this information for guidance only and will not be held responsible for oversights concerning defects or restoration, nor does a reference to a particular defect imply the absence of any others. Prospective purchasers must accept these reports as genuine efforts by Gorringes or must take other steps to verify condition of lots. If you are unable to open the image file attached to this report, please let us know as soon as possible and we will re-send your images on a separate e-mail.