We found 74887 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 74887 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

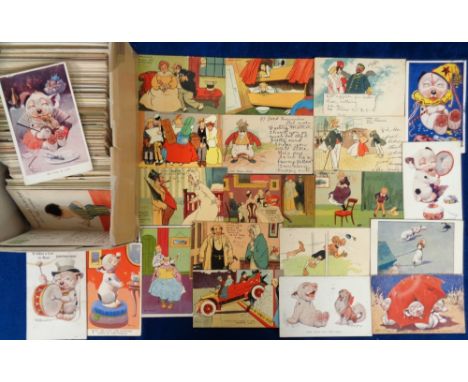

Postcards, Comic, a mainly mixed comic and children selection of over 400 cards with McGill (39), Attwell (10), Thackeray (6), Lawson Wood (4), Spurgin (7), Tom Browne (14), Studdy (Bonzo, 9), Dudley Hardy and much more. Also fairies (Outhwaite), hunting, military, witch, C.D Gibson, fire brigade, police, motoring, sport (cycling), bathing belles, Florence Hardy, Ethel Parkinson, advert for Buster Brown shoes, black humour, writing (ink), Scots, scouts (Ibbetson), appliqué (hair), write away, owls. Nice mix (mainly gd)

AN ITALIAN LACCA POVERA BOXLATE 18TH / EARLY 19TH CENTURYof sarcophagus form, decorated with a hunting scene and figures at various activities, the hinged top enclosing a vacant interior9.7cm high, 23.4cm wide, 12.5cm deepProvenanceThe Charrington Family Collection, Winchfield House, Hampshire.

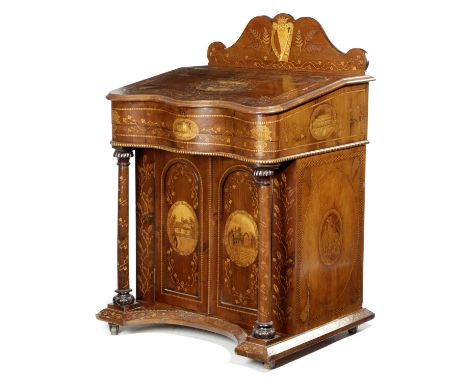

A LARGE VICTORIAN IRISH KILLARNEY YEW, ARBUTUS AND MARQUETRY DAVENPORTATTRIBUTED TO ARTHUR JONES, DUBLIN, C.1870inlaid with shamrock, hearts and oval panels depicting famous landmarks including Glena Cottage and Muckross Abbey, hunting figures and leaves, the hinged cover enclosing an interior with six drawers, above a writing slope and pen rests, in turn above pair of arched panel doors enclosing five further drawers each inlaid with an oval scene and foliage, flanked by a pair of columns inlaid with spiralling shamrock119.5cm high, 82.5cm wide, 67.5cm deepCatalogue noteThe Davenport being offered here has close similarities to a Davenport illustrated in G.Bernard Hughes, 'Development of the Davenport', Country Life, 1 July 1971, pl.5 and attributed to Arthur Jones of Dublin. Another, bearing the coats of arms of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on the doors, forms part of the collection of the Ulster Museum and is illustrated in B.Austen, 'Tunbridge Ware and Related European Decorative Woodwares', p.185, pl.88. Christie's London sold a further example as part of their Highly Important English Furniture Eastern Rugs and Carpets Auction, 29 March 1984, lot 135 and another was sold Bonhams, London 12 February 2002, lot 95.The inlaid scenes used on this Davenport are of well known tourist spots and are based on engravings of topographical works in the area.

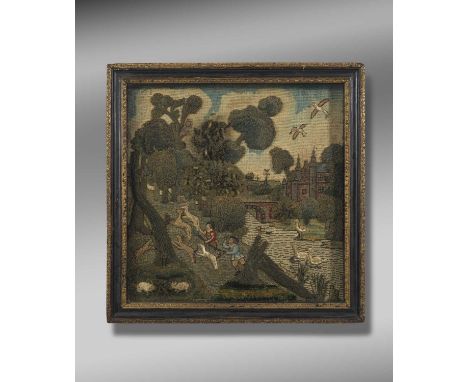

A CHARLES II STUMPWORK PICTUREC.1660-70worked in silks and metal thread in a variety of techniques depicting a hunting scene with figures and hounds chasing deer through raised-work trees before a river and with a large country house in the background, a painted silk owl perched in a tree, in a Hogarth style box frame34.5 x 34cmProvenanceThe Howard Collection of Oak and Works of Art.

An extensive collection of vintage cigarette and tea cards (Players, Wills, de Reszke, Wix & Sons etc) - sets and odds to include: WWI., Topographical views, Fighting & Civil Aircraft, Speed through the Ages, Famous Works of Art, Old Hunting Prints, Dr Who, Your Throat Protection, Racehorses and Jockeys 1938, The Bridges of Britain, Arms of Universities etc and 1 folder of silk silk Kensitas Cigarette Flags and Flowers; Ceramic Art etc [1 box with 6 folders - Q]

A Royal Worcester porcelain loving cup, printed with a hunting scene, after M Barlow, printed marks, 9.5cm high, together with five Royal Crown Derby Derby Posies dishes, commemorating the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2012, the Golden Wedding Anniversary of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and HRH Prince Phillip Duke of Edinburgh 1997, the 90th Birthday of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and the marriage of Prince Andrew with Miss Sarah Ferguson. (6)

A late 19thC Minton Hollins & Company pottery tile, relief moulded with a pair of greyhounds and hare, against a turquoise ground, within a brown geometric border, gilt framed, tile 15cm x 15cm, and a further green glaze tile, relief moulded with hunting dogs within woodland, in an oak frame, tile 20cm x 20cm. (2)

Two Royal Crown Derby porcelain teddy bears, one titled 'I Love You', together with a baby red rabbit paperweight, gold stopper, and a Royal Doulton porcelain miniature figure of Jessica, M261, boxed, and a pottery goblet, printed with a hunting scene, and internally 'Keep Hunting', 15cm high. (5)

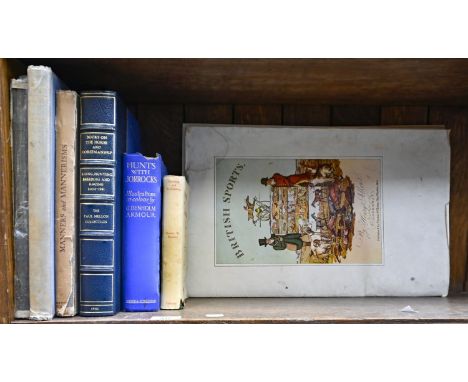

[SPORTING]. HUNTING Twenty assorted works, including Edwards, Lionel. A Sportsman's Bag, first edition, Country Life, New York, 1937, green cloth, eighteen mounted colour plate illustrations, large quarto; and Watson, J.N.P. Lionel Edwards, Master of the Sporting Scene, first edition, The Sportsman's Press, 1986, colour plate and black and white text illustrations throughout, quarto. Condition Report : Aldin Ratcatcher to Scarlet with damp marked covers. Condition reports are offered as a guide only and we highly recommend inspecting (where possible) any lot to satisfy yourself as to its condition.

Fine Binding. Bibliography: Podeschi (John B.), Books on the Horse and Horsemanship, 1400-1941, The Tate Gallery for The Yale Center for British Art, 1981, finely bound by Sangorski & Sutcliffe in blue three-quarter morocco gilt over cloth, signed, top edge gilt, marbled endpapers, 4to; two hunting works illustrated by Lionel Edwards; further fox-hunting and equine interest, (7)

An 18ct gold half hunting cased keyless lever watch, with three-quarter plate movement, marked SWISS MADE, enamel dial, gold cuvette and bow, 49mm diam, import marked London 1907, 94.3g The plastic replacement glass looseDial not cracked or chippedMechanism in working orderCuvette engraved with presentation inscription, dated 1912, case back engraved with monogramCase in good condition with little sign of wear or dents

A Chantilly porcelain cup 18th century, of barrel form, painted with two `dancing` storks flanked by flowers, the handle with applied trailing flowers,and another, painted in the Kakeimon style, with a moulded handle, both with hunting horn marks to base, 8cm & 6cm high (2)Provenance: The David and Sarah Battie Collection.Condition Reportbarrel cup, section of trailing leaver above handle missingother Chantilly cup, small chip to rimVienna, hairline crack

A COLLECTION OF COLOURED GLASS, comprising a 19th century hand painted glass pitcher depicting an English traditional fox hunting scene (large crack running around the base), a Royal Brierly 'Studio' pink iridescent vase, height 18.5cm (nibbles around rim), a blue Sklo Union Libochovice Glassworks 'Lens' vase, a group of five assorted Caithness vases (three have chips to rim, amethyst swirl has a large chip), a frosted glass Rosenthal 'Versace- Medusa' paperweight, an amethyst and white Murano glass dish, a Heron green iridescent glass apple, etc. (qty) (Condition Report: most obvious damage is mentioned in description)

This striking silver-plated stirrup cup features a detailed horse head design as its base, blending functionality with artistic craftsmanship. Stirrup cups, traditionally used in hunting culture, are ceremonial drinking vessels offered to riders while they remain mounted, often filled with port or other spirits. The term "stirrup cup" derives from the practice of presenting the drink to guests as they were about to depart for a hunt, symbolizing hospitality and good fortune. The cup boasts a smooth, reflective finish, while the intricately molded horse head showcases fine detailing in its mane and facial features. This piece is both decorative and practical, a unique addition to any collection of equestrian-themed or barware items.Issued: 20th centuryDimensions: 6"HCondition: Age related wear.

![[SPORTING]. HUNTING Twenty assorted works, including Edwards, Lionel. A Sportsman's Bag, first edition, Country Life, New Yo](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/80770453-8be5-4431-8bbe-b2a000a21315/fa42cdd3-bc05-42d9-9578-b2ac00d5a9d4/468x382.jpg)

![After Archibald Thorburn - Grouse, a pair, twice signed within the plate, n.d. [mid-20th c], coloured prints, 22 x 28cm;](https://cdn.globalauctionplatform.com/01594987-df52-4a65-b86a-b2ae00d1af13/3a38badd-f254-4ca5-aa95-b2ae00d3faf5/468x382.jpg)