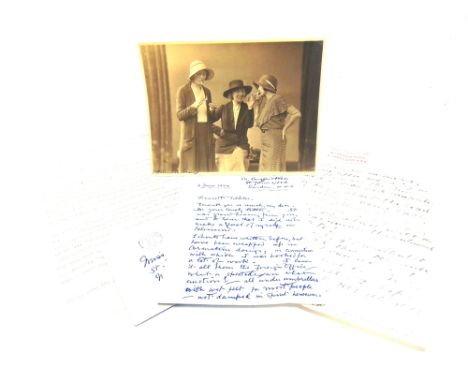

England Cap awarded to Cornelius “Neil” Franklin (24 January 1922 – 9 February 1996) Date: April 12, 1947 Location: Wembley Stadium Teams:England Vs Scotland Final score:1-1 Description:Cornelius “Neil” Franklin, an exceptional England defender, earned 27 caps between 1946 and 1950. Known for his composure, tactical awareness, and elegance, Franklin revolutionized center-half play. Capped 27 times by England, setting a record for consecutive England appearances,His international career ended prematurely after controversially leaving for Colombia’s Independiente Santa Fe in 1950, a move that impacted his legacy in English football history just months before England were set to make their World Cup debut in Brazil. Almost universally considered the greatest defender England have ever produced by those who saw him play, Neil Franklin is a football superstar whose name perhaps isn’t as well-known as it ought to be. The international cap is a blue 6 panel velvet cap embroidered with English Football Association badge to front and ‘E v S 1946-47’ to the peak, awarded to a player for a game v Scotland in 1946/47. This England cap was awarded to Neil Franklyn for his participation in the British Championship match vs Scotland https://www.englandfootballonline.com/TeamPlyrsBios/PlayersF/BioFranklinC.html Further Details Club Stoke City and England Name Cornelius "Neil" Franklin Season 1946/47 Match England vs Scoland Condition Excellent Cindition, preserved in a frame Provenance Vendor purchased a charity auction where cap was donated by Franklin

We found 31242 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 31242 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

An Adidas blue and white BRIGHTON & HOVE ALBION 1983 FA Cup Final v Manchester tracksuit and bottoms, the top with zip up front embroidered badge and seagull emblem with FA CUP FINAL WEMBLEY 1983 in red lettering [2] The first game, which took place on May 21st 1983 at Wembley Stadium, ended in a 2-2 draw with the replay taking place five days later, a game that saw Manchester United win 4-0.

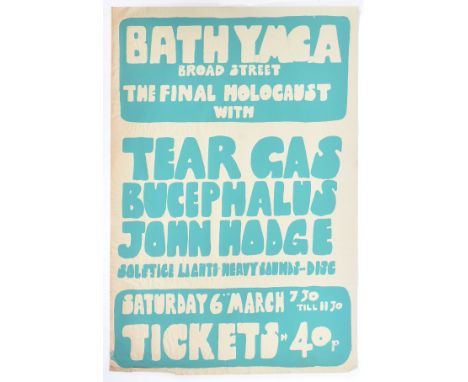

Music Poster - an original believed late 1960s or early 1970s Prog Rock concert poster from the Bath YMCA on Saturday 6th March featuring bands Tear Gas, Bucephalus and John Hodge. The gig under the banner of 'The Final Holocaust'. Locally screen-printed on white, with green text. Some folds to the lower edge and a small tear, otherwise in very good original condition for its age. Measures: 76cm x 50cm. A scarce surviving poster, possibly the only surviving example. Tear Gas were a progressive rock band formed in the late 1960s in Glasgow and initially comprised of members Eddie Campbell (keyboards), Zal Cleminson (guitar), Chris Glen (bass, vocals), Gilson Lavis (drums) and Andi Mulvey (vocals). Their first two albums were met with a lacklustre response from the critics. Despite regular touring in an effort to establish themselves, it was not until they teamed up with Alex Harvey in August 1972 to become the Sensational Alex Harvey Band that they saw any real success.

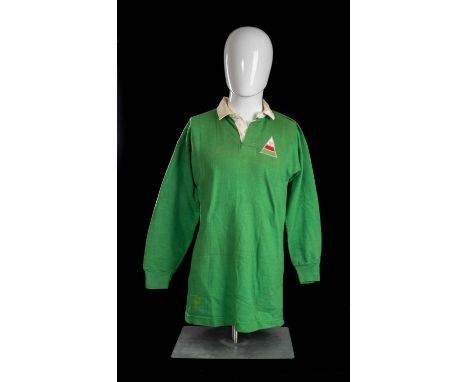

JPR WILLIAMS | YR URDD JUBILEE MATCH | 1972Match-worn by JPR Williams, the jersey in green with white collar, Urdd logo to chest with ‘50’, number 15 stitched to reverse, Umbro ‘Choice of Champions’ label. The match comprised a Barry John XV against a Carwyn James XV, played as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of Urdd Gobaith Cymru on April 26th 1972.Most spectators were expecting just another entertaining afternoon, a commemorative match, the sort of which were popular in the amateur period. The game itself was originally scheduled for Cardiff Arms Park, but moved next door when it became clear the demand was huge to see what was, in effect, a game between a Wales XV and a quasi-Lions XV. In the end, 35,000 fans saw the John XV beat the James XV, 32-28. JPR was to play against his English rival and friend Bob Hiller.However, the match will be forever remembered for altogether different reasons.Just a few days after the game, Barry John ‘The King’ announced that he would walk away from rugby at the age of only 27. The news creating shockwaves through the sporting world.Phil Bennett was the opposing number to Barry John in the Urdd match and being four years John’s junior, was very much the heir to Barry John’s throne.Bennett recalled “For the public back then, Barry’s decision was a huge sensation – but I have to admit that it was less of a shock to me. He was a huge star, there would be pictures of him and George Best in the newspapers of the day because that was the level of fame he’d had since coming back from New Zealand with the Lions in 1971. But Barry wasn’t a film star. He was young guy from a West Wales village, and it was already being talked about that he found that side of things quite difficult.He’d go for a pint and there would be six blokes queueing up to get an autograph and ask him questions. He would go to some function and no-one would give him a minute’s peace. So, there were rumours among the boys that he wasn’t happy. You have to remember this was an amateur game. Barry played for fun, for the enjoyment. Yes, he wanted to win every game he played, but it wasn’t life and death to him and it wasn’t his job.”

BOB HILLER | ENGLAND | 1969 / 1970 / 1972Jersey match worn by Robert Hiller (b.1942), traditional all-white, embroidered three colour rose on stem with toned leaves, black felt number 15 to reverse, Umbro International label to the interior (size 42ins). To accompany:Programme Wales vs. England 12th April 1969, both JPR and Hiller’s names therein.Programme Wales vs. England at Twickenham, dated 1970.Hiller and JPR became good friends on the Lions tour of New Zealand in 1971 when Hiller was appointed captain for one of the mid-week matches. JPR commented that "…Bob was one of the great characters of the tour. He really kept us above water with his remarkable humour" it was said that Hilller was always able to raise the spirits of the tour party,Hiller scored a fabulous 102 points from ten games for the Lions in New Zealand and had scored 108 points in South Africa in 1968.JPR (family notes, 2023):“I had played against Bob a number of times before ‘71: either for London Welsh against Harlequins or for Wales v England. I respected him and liked him. I liked him even more in ‘71 when we finally arrived in NZ via many airport stops and two poor games in Australia. Early on, he took me aside and said to me he thought I would be the Test team Full back and that he would mostly be in the T’s and W ‘s and that we would support each other.. He was an experienced Lion and knew about the midweek games. He was a wonderful tourist and scored around 100 points for us in the three months. After team training, Bob and Barry (John) would stay behind to practise goal kicking. I stayed as well to gather the balls and punt them back to them. The rest of the team were surprised that I could drop a goal from near the halfway line…. but not Bob! I learned a lot from him. And also from Barry, but he had such flair, was such a natural that no-one could copy him... a magical player. In later years, I would meet up with Bob Hiller after Twickenham matches. He would instruct the doorman (to the Ex players room) to expect me and we would have great catch ups.”Hiller earned 19 caps for England between 1968 and 1972 as a fullback, known for his reliable goal-kicking and strong defensive skills. He captained England seven times and represented Harlequins at club level. Hiller was particularly known for his accurate kicking, both for goal and tactical play. Although he did not play in any British Lions test matches, he was part of two British Lions tours.In the Radio Times, 26th February 1970, John Hopkins interviewed both JPR and Hiller before their Five Nations match at Twickenham, with Hiller as captain."Hiller is the sort of kicker who will put one over from the touchline when his side is one point down with a couple of minutes to go".JPR in the same article said "On his day, Bob is one of the best kickers in the world. And he has an uncanny knack of intercepting. He’s a good bloke off the field too. I once saw him with his fiancée in a pub around the corner from here and we had a drink or two together".JPR and Hiller remained life-time friends.Additional playing days images courtesy of Colorsport (Copyright)

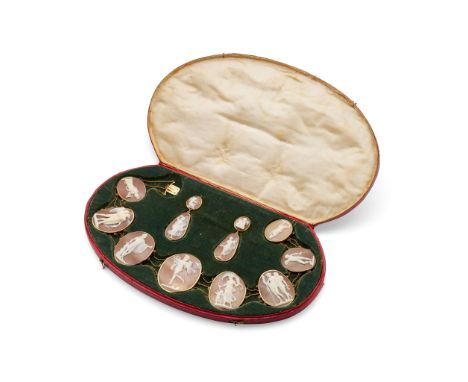

An early 19th century cameo necklace and earring suite The graduated collet-set oval shell cameos, depicting figures from Classical mythology including Venus and Cupid, Hermes holding a caduceus and twin babies, the goddess Hygieia and a discus player, linked by triple chain connectors, pendent earrings en suite depicting the muses, largest cameo 4.8 x 3.8cm, lengths: necklace shortest strand 42.7cm, earring 6.1cm, fitted case (2) The interest in cameos was burgeoning in the 17th and 18th centuries and came to its apex during the Napoleonic period (1799-1815). These decades saw yet another revival of classical antiquity largely pushed by the political transformation of France into an empire. Educated members of society displayed an outward appreciation for the classics, notably the Roman Empire, through cultural and aesthetic choices.While in proceeding centuries the study of cameos had been predominantly a male-dominated interest, the late 18th to early 19th century saw the integration of these classical themes, including in cameos, into women's dress and jewellery fashion. This necklace for instance has a heavily female theme in the nature of the mythological figures and scenes represented. Despite the Napoleonic Wars, this classical revival made its way to Britain, in part driven by the Empress Joséphine (1763-1814), widely regarded as a source of fashionable inspiration across Europe.As a portable sculpture or portrait, cameos offered an intersection of culture and tourism meaning well travelled Victorians could buy jewellery souvenirs and through personal adornment demonstrate their erudition.

Registration No: JYF 56 Chassis No: 22096 MOT: ExemptHandbuilt and among the nicest Specials we have encounteredBespoke aluminium body, Lucas P80 headlamps plus bespoke instrumentsLeather seats and aluminium machined dashboard19" wheels with new Blockley tyresEntering production in 1946, the new Alvis TA14 was a successful update of the pre-WW2 12/70 (designed by George Lanchester). With a two-inch longer wheelbase and four-inch wider track as well as some additional chassis bracing, it offered an improved ride and sharper handling. Credited with 65bhp, its 1892cc OHV four-cylinder engine was mated to a four-speed manual gearbox (with synchromesh on the top three gears) which drove the rear wheels. While the majority were supplied as Mulliner-bodied four-door saloons, the TA14 could also be had with two-door drophead coupe coachwork by Carbodies or Tickford. A number of examples have been turned into specials like the sale example with lightweight coachwork.JYF 56 chassis number 22096 Was dispatched on the 26th of May 1948 to the Alvis agents Brooklands Motor Car Company Ltd of Bond Street London, The coach Builder selected by the client was. Mulliner, JYF 56 has been known to the Alvis Owners Club since 1968, In 2010 a previous owner embarked on making a stylish special , 2014 saw the baton passed to the current owner, who successfully finished the aluminum coachwork in 2016,A Foundry was commissioned to cast the bespoke sandcast alloy bulkhead (25 kg in weight) This is the Foundation, for the cars aluminum coach work, A matching 19 " wheel Rim is supplied, with the car, that could be supported by the substantial bulkhead, to give the benefit of a spare wheel side mounted outside for longer events or touring,,ectTo ease entry of the cockpit the steering wheel is quick release, the external mounted handbrake is a racing fly off type, The set up of the supercharger (Eaton) is 5 psi driven through twin belts, from the crankshaft, With a Hd8 SU 2" carburettor running a polished 125 VE needle, featuring a CAD designed cast aluminium let manifold with blow off valve, the distributor at considerable expense was built for the cars blown motor by the Distributor Doctor Ltd, a print out graph is supplied, The late engine tuner Peter Baldwin, services were engaged for the engine setup, The engine has been fully stripped cleaned, parts replaced as necessary, compression ratio calculated, it has only ever run on penrite, oil in this ownership, access to the battery and storage behind are behind the leather seatTo compliment the engine set up, A sand filled bespoke exhaust manifold and system was commissioned,The front shock absorbers are by Andre Hartford, brakes have been re-lined, The springs have been refurbished by Jones Springs Ltd, a bespoke leather bonnet strap commissioned by vintage supplies, all chrome is triple plated by a leading UK Plater, The car benefits from a new professionally made wiring loom with a new period looking alternator, to support the electric fan and other demands of today touring activitiesNew hubs were supplied by Orson equipment Ltd at considerable expense, a discrete modern GPS speedo and trip is fitted to the machine turned dashboard, consideration to engine access is further improved by easy removal of bonnet side panels, As is the attractive supercharged carburettor cover, complete project is an excess of 3,000 hours In summary JYF 56 is registered with the Department of vehicle licensing (DVLA) Swansea as a convertible, two seater, Also the special status, is supported as legitimate and laudable by the Alvis Owners Club, and the records they hold for the car updated, paperwork& lots of invoices included a sale For more information, please contact: James McWilliam james.mcwilliam@handh.co.uk 07943 584760

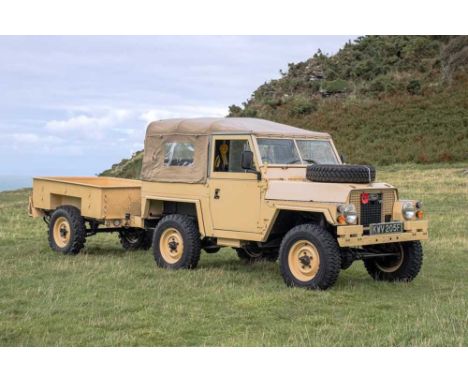

Registration No: KWV 205F Chassis No: CC64633L0 MOT: ExemptAward winning example with well-received features in Land Rover MonthlySubject to a comprehensive restoration in 2005 including several upgrades to the gearbox, chassis, suspension and brakesFitted with the popular Rover V8 engineComes with a comprehensive history fileBelieved to be 1 of just 2,989 ever made The Land Rover Half-Ton, better known as the Lightweight or Airportable, was based on the Solihull firm’s Series IIA 88-inch model. Intended for use by the British Armed Forces, the newcomer was narrowed by four inches and fitted with more readily detachable panels. Otherwise, it remained true to ‘Series’ Landie practice with a 2.25-litre petrol engine, 4WD system and leaf-sprung suspension etc. Less heavy than a standard model (but only when shorn of its doors, hood frame and removeable panels), the Lightweight was accepted by the Ministry of Defence. Produced from 1968-1984, 2,989 were reputedly made. Reputed to have seen service with the RAF, this multiple award-winning and magazine-featured Lightweight acquired its current desert camo paintwork as part of an extensive restoration. Carried out in 2005 by a previous keeper, work saw the Landie fitted with a replacement chassis, uprated disc brakes and coil-sprung suspension. The original 2.25-litre four-cylinder engine was supplanted by a 3.5-litre Rover V8 which in turn was allied to a reconditioned Series III ‘Suffix C’ gearbox. Sporting a stainless steel exhaust system, the ex-military machine is further adorned with a bonnet-mounted spare wheel and rear-positioned shovel and pickaxe. Offered for sale with a matching Sankey trailer, this wonderful Lightweight is also accompanied by a V5C Registration Document, large folder of invoices and ribbons from its numerous car show wins. For more information, please contact: James McWilliam james.mcwilliam@handh.co.uk 07943 584 760

Registration No: VHN 177 Chassis No: TS2304 MOT: ExemptAcquired by the vendor, an accomplished engineer, during the Covid-19 Lockdown and treated to an exhaustive and wholly uneconomic restoration!Potentially eligible for the Mille Miglia Storica as a 'Long Door' plus other prestigious eventsKept deliberately stock with the exception of the gearlever activated overdrive and hi-torq starter motorBumpers come with the car (but are not fitted)Refinished in its factory colours (albeit with leather upholstery)In the context of industrial Britain's post-war 'export-or-die' drive, the personal rivalry between Jaguar's William Lyons and Standard-Triumph's Sir John Black only served to increase pressure on the latter's new sportscar project. Unveiled at Earls Court in 1952, favourable public reaction saw Triumph charge Ken Richardson with the task of translating its Type 20TS show car (often referred to as TR1) into production reality. Embarking on an intensive research and development programme, he designed a bespoke chassis built around an eighty-eight inch wheelbase. Equipped with independent coil sprung front suspension, a live rear axle and all round drum brakes, it was powered by a revised version of the company's 1991cc, OHV Vanguard engine. Developing an unstressed 90bhp this torquey unit was mated to a four-speed plus overdrive gearbox. Differing from the Type 20TS in offering a boot and internal spare wheel location, the prototype TR2s proved unexpectedly fast as witnessed by the 125mph (race trim) and 105mph (road trim) maximums posted by Richardson on a closed section of Belgian Jabbeke highway in Spring 1953. Deemed ready, the first production TR2 emerged in July that year. A decidedly rare survivor as an early, ‘Long Door’, home market, matching chassis and engine numbers example, chassis TS2304 was acquired by the vendor in July 2019. An accomplished engineer, he subjected the Triumph to an exhaustive and wholly uneconomic restoration during the Covid-19 lockdown. Off the road for decades, the TR2 had reputedly had its engine and chassis refurbished in the late 1980s / early 1990s but the wingless body was in a parlous state. The four-vent bonnet, boot lid and doors were present and the seller managed to reconstruct the tub using the renewed beams underpinning the ‘A’ and ‘B’ posts as fixed datum points. Not easily deterred, he spent three days refining the bonnet release mechanism. The completed body was painted on a rotisserie and the engine stripped to check that the earlier overhaul had been done properly. The gearbox and overdrive unit were rejuvenated and the propshaft balanced. The overdrive switch was incorporated atop the gearlever. The carburettors and fuel pump were renovated and a stainless steel exhaust system fitted. The original Triumph front wishbones did not permit camber angle adjustment and so were substituted for bespoke items which did. The project also encompassed the following new / reconditioned components: brake master cylinder / copper lines, aluminium fuel tank, copper fuel lines and matched sender unit, renovated (or new) instruments and drive cables, rejuvenated wiper motor, refreshed radiator together with Revotec Electric Fan and manual override and replacement wiring loom (changing the polarity to negative). The original dynamo was refurbished, a “hi-torque” starter motor added and new seat frames trimmed in leather to the original pattern. The previously re-chromed windscreen frame received new laminated glass and wind deflectors. A new hood, tonneau cover, fire extinguisher, Michelin X radials, carpets, headlights and sound deadening material were sourced too. Refinished in its original colours and potentially eligible for a host of VSCC events plus the Mille Miglia Storica, this delightful TR2 is worthy of close inspection. A full photographic record was kept of the restoration journey as well as receipts for parts and sub-contracted work (panel welding and painting) KEY ORIGINAL SPECIFICATION FEATURES:UK registered from new (Green Log book, Heritage Certificate), and restored to original factory colours and specification eg. drum brakesEligible for VSCC events (current “buff form”) and Mille Miglia RetroCorrect internal dual bonnet catches, painted bonnet and boot catchesFabric style piping (not chrome)4 vent bonnet and correct internal catchesSupplied with the car are: correct jack, side screens (In need of reconditioning), new front and rear bumpers (not fitted), workshop manual and owners handbook. For more information, please contact: Damian Jones damian.jones@handh.co.uk 07855 493737

Registration No: SJW 842S Chassis No: XL2S1N420542A MOT: ExemptFirst prize in a competition to celebrate HM Queen Elizabeth II's Silver JubileeWarranted 5,500 miles from newRetained by its first owner for thirty-one yearsStored in a temperature controlled environmentThis remarkable Mini 1000 is warranted to have covered just 5,500 miles from new. First prize in a competition held by St Cuthbert’s Co-op and Colgate toothpaste to celebrate HM Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee, the diminutive saloon’s paintwork is reputedly a non-standard hue that was specially applied to commemorate the occasion. Won by an Edinburgh school teacher, Margaret Irvine, her lack of a driving licence saw ‘SJW 842S’ remain garaged for the first three years of its life. Driven sparingly, the four-seater had covered a mere 2,000 miles or so by the time it was bought by one of Miss Irvine’s neighbours during 2008. Another lady, the latter sold the Mini 1000 to her brother who then passed it to his son. Finally leaving the Everett family’s custody in 2021 when it relocated to Suffolk, the Silver saloon remains notably original. The contrasting Dark Blue vinyl upholstery is as well preserved as one might expect and the supplying dealer’s rear window sticker and tax disc holder are still in situ. The factory-fitted tyres were swapped for fresh rubber some years ago but have been kept for posterity. Surely unique given its backstory, this delightful Mini is offered for sale with V5C Registration Document, Competition Winner’s Telegram, numerous old MOTs and other paperwork. MOT History: 17th August 1984 - 408 miles 19th November 1987 - 1,435 miles 18th September 2008 - 2,083 miles 1st October 2009 - 3,448 miles 5th October 2010 - 3,678 miles 24th October 2011 - 4,802 miles 25th September 2012 - 4,892 miles 22nd January 2014 - 5,053 miles 21st February 2015 - 5,238 miles 22nd October 2016 - 5,373 miles 24th October 2017 - 5,386 miles For more information, please contact: Baljit Atwal baljit.atwal@handh.co.uk 07943 584762

Registration No: 1688 D Chassis No: AM107.1108 MOT: ExemptUnderstood to have been registered new in Switzerland before being resident in Italy until 2006Subject to a photo documented engine overhaul, which was completed at 60,100kms in 2007Subject to a cosmetic overhaul in 2020Offered with extensive history file including original Maserati documentationMatching numbers example with good provenancePlease Note: The photos were taken at short notice and before a planned valet had taken place. As such, the vendor does not believe they are an accurate representation of the Maserati's condition. It will be re-photographed at the venue.Introduced at the November 1963 Turin Salon, the Maserati Quattroporte was arguably the world's first 'super saloon'. A bold move on the part of the Casa del Tridente-owning Orsi family, the newcomer was part high-performance GT and part luxury limousine. Taking inspiration from the Maserati 5000GT he had penned for Prince Karim Aga Khan in 1961, Pietro Frua imbued the handsome Quattroporte with a low belt line, slim-pillared glasshouse and neatly defined yet spacious boot. Based around a unique sheet steel box-section chassis equipped with independent front suspension, a de Dion rear axle and four-wheel disc brakes, the four- / five-seater was powered by a race-bred 4136cc 'quad-cam' V8 engine allied to either five-speed ZF manual or three-speed Borg Warner automatic transmission. Credited with developing some 260bhp and 267lbft, the Maserati was reputedly capable of 0-60mph in around 8 seconds and over 140mph (depending upon the final drive ratio chosen). After the first few cars had been made, Quattroporte production was transferred from Carrozzeria Frua to Carrozzeria Vignale (though, Maggiora of Turin was responsible for fabricating the bodywork). Arriving in 1966, the updated Series II version (or Tipo 107A as it was known by the factory) sported a new quad-headlamp visage and revamped interior complete with lustrous wood cappings, electric windows and standard fit air-conditioning. While, under the skin a revised leaf-sprung Salisbury back axle resulted in a quieter, smoother ride. Stylish, fast and exclusive, the big Maser was driven by the likes of Marcello Mastroianni, Prince Rainier of Monaco and Conte Volpi di Misurata. Manufactured during October 1966, chassis AM107.1108 is an early Series II car that was specified with the desirable five-speed ZF manual gearbox. Finished in the stunning combination of Beige Mirabello Metallic matched to Marrone Connolly leather upholstery, it is thought to have been supplied new to Switzerland. Known to have been resident in Milan by February 1972 and to have relocated to Modena eight years later, the Maserati reputedly had three keepers prior to being acquired, and imported to the UK, by its previous owner during 2006. Treated to a thorough engine overhaul not long afterwards at an indicated 60,100km, the V8 was fitted with new piston rings, bearing shells and timing chains as well as having attention paid to its oil pump and cylinder head. Gaining a new Kevlar clutch and refaced flywheel at the same time (with the associated machining work being done by Crosthwaite and Gardiner), the four-seater also had its carburettors adjusted. Well maintained thereafter, the Quattroporte was invited by Maserati UK to form part of its stand at the 2011 Goodwood Revival Earls Court Motor Show re-enactment. The front suspension and steering were refurbished in 2018 and the car repainted in its original hue during 2020. Benefiting from a replacement Marelli distributor in 2023, that same year saw the four-seater cosmetically enhanced still further with sundry trim and glass pieces. Starting readily and running well during our recent photography session, it is rated by the vendor as being in ‘very good overall’ condition. Pleasingly retaining its original, and well preserved, upholstery, the Quattroporte now shows some 76,000km to its odometer. Offered for sale with V5C Registration Document, original owners’ handbook, Maserati leather wallet, numerous receipts, engine refurbishment image CD and copies of the Italian registration documents etc For more information, please contact: Luke Hipkiss luke.hipkiss@handh.co.uk 07886398226

Registration No: 121 LUE Chassis No: LML 773 MOT: Exempt Long term ownership since since May 2003Meticulously maintained with a comprehensive history fileEnjoyed on many European tours with the AM Owners ClubRegularly serviced by specialists Roses Garage, Sandwich, Kent1 of 565 examples produced, finished in black over cream leather Introduced at the October 1953 London Motor Show, the DB2/4 represented a new breed of longer-legged, more accommodating Aston Martin. Panelled in lightweight aluminium over an advanced tubular frame chassis, it featured independent front suspension via a sophisticated trailing link, while at the rear a Panhard rod assisted radius arms in keeping the coil-sprung beam axle firmly tied down. Initially powered by a 2580cc version of the famous Willie Watson / W.O. Bentley designed DOHC straight-six engine, the adoption of a larger 83mm bore size saw capacity rise to 2922cc in mid 1954. The 2.9 litre unit was credited with developing some 140bhp sufficient for a quoted 120mph top speed.Coming from long term ownership, the vendor having acquired the car in May 2003, this DB2/4 is accompanied by a comprehensive history file which includes research into previous owners (eleven in total being identified to date) together with a fascinating record of works carried out (some even with mileage covered at the time) dating back to October 1954. Supplied new by dealer Martin Walters of Dover, whose plate remains inside the glove pocket, and assigned the registration mark TKM 13, the first recorded keeper was a John William Marsh. Seemingly retained by Mr Marsh until 1970, the car then change hands a few times in the early part of the decade before being acquired by a Richard Prentice in 1975 who kept it up until 1989. Sold at auction in 1990, it is thought a sum of c.£65,000 was paid by the new owner, Felicity Mary Henriques. Various mechanical works are recorded as being carried out during the mid 1990s including by specialists Tony Curtis and Aston Services Dorset, whilst the headlining was also renewed with West Of England cloth and new Wilton carpets fitted.In 1997 the car passed to Patrick Mulligan who confirmed to the vendor some major mechanical work was completed during 2000/2001 along with a respray in black. Around £15,000 was invested but only around 200 miles covered in his ownership. In May 2003, 121 LUE was purchased by the vendor in whose ownership it has been enjoyed on numerous events, including European tours, with the AM Owners Club and maintained to a high standard. Since acquisition the car has been regularly serviced by specialists Roses Garage of Sandwich, Kent. The vendor’s research confirms the engine number VB 6J 249 and chassis number LML 713 to be original. 1 of 565 examples produced, it is attractively finished in black over cream leather. For more information, please contact: John Markey john.markey@handh.co.uk 07943 584767

Registration No: BEH 504C Chassis No: B9472725 MOT: ExemptUnderstood to be 1 of just 3,763 MK1 cars (the vast majority of which were built to LHD specification)Acquired by the vendor, an accomplished engineer, as a stalled restoration projectKnown to the Sunbeam Tiger Owners' Club for many years and pleasingly retains its original 260ci engineDiscretely uprated cooling system and 14-inch Minilite-style alloys but otherwise essentially stockCredible but unwarranted 73,000 milesAccompanying history file includes photos of the restoration / reassemblyThe Sunbeam Tiger was conceived in the West Coast of the USA and inspired by the success of the AC Cobra - the result of mating an American small block V8 engine with the British AC Ace. Rootes American Motors Inc. saw the potential for inserting the same powerplant - Ford's 4.2-litre (260 cu in) 'Windsor' unit - into the nose of the stylish but rather pedestrian Sunbeam Alpine. Carroll Shelby was duly commissioned to build the prototype and the rest is history. The basic layout of the Alpine was retained and the car featured independent suspension at the front using coil springs, and a 'live' axle at the rear supported by semi-elliptic leaf springs. The 164bhp engine endowed the newcomer with a top speed of around 120mph and a 0-60 mph acceleration time of under eight seconds. A total of some 7,085 Tigers were eventually produced. Among the mere 800 or so ‘home market’ Sunbeam Tigers, chassis B9472725 was granted the Stoke-on-Trent number plate ‘BEH 504C’ during June 1965. Showing just three former keepers to its V5C Registration Document, the 2+2-seater was acquired by the last of these in 1989. Taken off the road not long after, the Sunbeam was carefully disassembled pending restoration. Work progressed as far as having the original 260ci (4.3 litre) Ford V8 engine overhauled, the bodywork repaired and the four-speed manual gearbox refurbished. Well-stored over the next three decades, the Tiger was complete when the vendor took possession during July 2023. Receipts for work done were reassuring as was the state of replacement parts. An accomplished engineer, the seller set about reassembling the Roadster and ‘double checking’ the previous works. To this end, the fuel system was rejuvenated with a new pump and lines, the electrics and instruments tested, the braking system renovated (the front discs being uprated to Princess 4-pot callipers; a popular period mod), the engine tuned (complete with uprated Edelbrock manifold and carburettor), the ignition system renewed, the cooling system upgraded (high output water pump, increased radiator size, Revotec electric fan with manual override, larger mechanical fan and bonnet louvres) and the suspension treated to new dampers (x4) and rear spring bushes (fittings are in place for a Panhard rod and tramp bars but neither have been installed). Thoroughly stripped, the bodywork was painted Giallo Fly, sound deadening added to the floors, a fire extinguisher and new seat belts added and the replacement hood and screen professionally fitted. Strating readily and running well during our recent photography session, ‘BEH 504C’ has been known to the Sunbeam Tiger Owners’ Club for decades. Decidedly unusual as a ‘home market’ Tiger with matching chassis and engine numbers, it is offered for sale with an original workshop manual, Alpine owners’ handbook (for hood raising / lowering instructions), emergency tyre repair kit, correct jack and wheel brace plus assorted restoration photographs and invoices. For more information, please contact: Damian Jones damian.jones@handh.co.uk 07855 493737

Registration No: T827 SGJ Chassis No: WBSBK92040EX67138 MOT: March 2026Reportedly completed during the penultimate month of productionWarranted 43,000 or so miles from newOffered with original book pack, service book, purchase invoice, MOTs, 2 spare keys and Radio card.Desirable Six speed manual transmissionStored in a temperature controlled garageFaster and more refined than its homologation-bred predecessor, the second (E36) generation of BMW’s iconic M3 debuted in November 1992. Initially available in Coupe guise, Convertible and Saloon variants were added two years later. Boasting the highest specific power output of any normally aspirated engine in the world (96bhp per litre), the BMW’s 3.0 litre straight-six developed some 286bhp and 232lbft of torque. Sitting some 31mm lower than its 3-Series siblings, the E36 M3 utilised the same multi-link rear axle as the marque’s Z1 Roadster together with thicker anti-roll bars and uprated springs/dampers. Judged by ‘Car and Driver’ magazine to be the finest handling car that money could buy in 1995, the following year saw the BMW gain a more potent 3.2 litre engine (320bhp / 258lbft) and six-speed manual transmission. Marketed by BMW GB as the M3 Evolution, the E36 M3 3.2 was reputedly capable of 0-60mph in 5.6 seconds and limited to 155mph. Only 2,107 of the 71,242 E36 M3s made were RHD Evolution Convertibles. A notably late example completed during the penultimate month of production, chassis EX67138 was supplied new by BMW Cooper of Thames Ditton on 20th July 1999. Finished in the stunning combination of Techno Violet with Black leather upholstery and a Black soft-top, the M3 is warranted to have covered just 43,000 or so miles from new. Maintained by main dealers and marque specialists, the Convertible underwent its ‘running in’ service on 9th December 1999 at 2,365 miles, while its last oil and filter change was carried out at 42,301 miles. Riding on fresh Michelin Sport tyres, the BMW is further understood to have had attention paid to its brake hoses / pipes / fittings, rear shock absorbers / top mounts and both front lower arm bushes. Reportedly covering a few thousand miles during the current nine-year ownership but ‘never in wet or wintry conditions’, the M3 has been uprated with a ‘short shift’ kit (however, the original gear lever has been retained). The spare wheel looks unused, the tool kit is complete and the Convertible even retains its glovebox torch! Deemed to be as well preserved as its low mileage would suggest, this increasingly collectible E36 is offered for sale with V5C Registration Document, book pack, two keys and Tracker. For more information, please contact: Baljit Atwal baljit.atwal@handh.co.uk 07943 584762

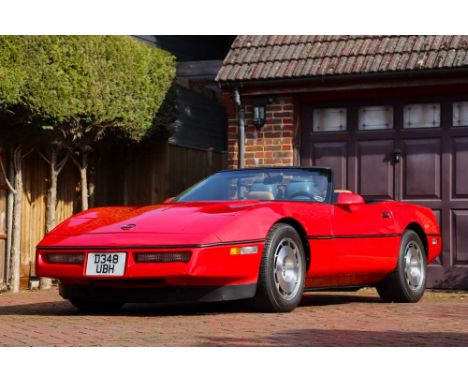

Registration No: D348 UBH Chassis No: 1G1YY6787G5905383 MOT: June 2025Number 5,383 of 7,315 C4's built to Indy 500 pace car specificationSupplied with the original owners handbook displaying 1986 Indy 500 winner Bobby Rahal's autographImported to the UK in 1992Described as an extraordinarily original car with only 49,989 miles displayed on the odometerArguably the most radical 'Vette in two decades, the fourth generation or C4 model was introduced in March 1983. Built around a C-section beam-reinforced monocoque, it was equipped with composite transverse-leaf independent suspension and rack and pinion steering. Fitted with 16 x 8.5 alloy wheels shod with P255/50VR-16 tyres as standard, the C4's handling drew considerable praise from the contemporary press. Powered by a 350ci/5.7-litre V8 engine mated to either four-speed automatic or manual gearboxes, it was reputedly capable of 0-60mph in under six seconds and over 140mph. Boasting new aluminium callipers, its four-wheel disc braking system proved more efficient than ever. Noticeably lower-slung than its predecessor, the new car actually possessed greater ground clearance (thanks to a cleverly routed exhaust) and a more spacious interior.In 1986, to celebrate the launch of the new C4 Convertible, Chevrolet supplied 56 Corvettes as pace cars and official vehicles for the Indianapolis 500. Chevrolet saw a great marketing opportunity in making replicas available to the general public. The cars actually used at the track sported Yellow paint, but all 1986 Convertibles were considered Pace Car Replicas. The open-top option added $5,000 to the price of the car, and 7,315 were produced out of the 35,109 total Corvettes sold that year. Supplied in Red, Silver, Black, Gold and Yellow, the C4 Pace Cars were fitted with a commemorative dashboard plaque and were all identical in specification, with brushed alloy wheels and tan leather interior.Our Corvette was delivered in September 1986 to Palm Harbor, Florida, and is said to have been supplied to none other than Bobby Rahal, who won the 1986 Indianapolis 500 Miles race and was the first driver to complete it in under three hours, driving a March 86C. The Corvette was later sold through Florida’s Toy Store dealership, with Mr. Rahal’s signature in the owners handbook, and was imported into Britain in 1988.Besides its provenance, this Corvette represents one of the best-preserved C4s in existence. We understand the paintwork is all factory-applied, and the interior is evidently original and complete with its Indianapolis commemorative plaque. The car has been cherished as a collector’s item from early in its life, having enjoyed single ownership from November 1992 to March 2024, while the MoT record beginning at just over 28,000 miles in 1990 suggests the present mileage of just under 50,000 is genuine. The paint and exterior exhibit only a light patina, concomitant with a well-cared for but unrestored car.The Corvette starts well and runs sweetly, and all of the gauges and switches are to said to function as they should. It is offered with the current V5, a large collection of MoT certificates and the original signed handbook. For more information, please contact: Lucas Gomersall lucas.gomersall@handh.co.uk 07484 082430

Registration No: HUE 25 Chassis No: 3842125172 MOT: ExemptIn the same family ownership since the 1950'sFitted with a crane unit during civilian life and used to haul engines from Avon river boatsOffered as an exciting project in need of complete restorationUnderstood to have been used in Desert Theatres during World War IIThe Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) truck refers to a series of military vehicles used during World War II and in the post-war period that were produced in Canada and were based on British designs. The CMP trucks played a crucial role in various military operations and logistics during that time. They were manufactured in large numbers and came in various configurations, including cargo trucks, artillery tractors, ambulance vehicles, and mobile workshops, among others. They were used for transporting troops, supplies, and equipment both in a range of theatres. Most CMP trucks were manufactured by the Canadian Chevrolet division of General Motors and Ford Motor Co, Canada. Some 410,000 CMP trucks were produced and it is understood that GM produced variants alone represented 201,000 of these. The Chevrolet version was offered with a six-cylinder GM engine and was produced in many different weights with short and long wheelbase variants and offered with 2x4 and 4x4. The C15 and C15A were rated at 15CWT with a 101-inch wheelbase and were 2-wheel drive and 4-wheel drive respectively.According to the vendor, chassis 3842125172 is understood to have been built as a Military Van during 1944 and served in the Desert Theatres during World War II, and particular reference was made to Tunisia. Staying within the military until 1949, the V5 records that it was first registered as 'HUE 25' when sold into private ownership on British shores and was by this time sporting a flat-bed body. The vendor's father is understood to have purchased 'HUE 25' and saw immediate potential in fitting a crane to its deck and using it to haul engines out of his collection of working river boats that offered tours of the River Avon from Stratford. The vendor fondly remembers that his first driving experience was being thrown into the cab at the age of 16 and learning to operate the crash-gearbox and centre throttle - being told by his father that he would 'soon learn'.Some years later, the flat-bed was laid up due to the river boat operations being ceased and remained undercover in the firm's yard until the vendor's father's passing some years ago. Said to have been run some years ago and due to be removed from its current place of rest, the vendor has advised that it would make a fantastic restoration project for any budding military vehicle enthusiast and has informed us that it comes with an old-style V5 showing 0 former keepers. For more information, please contact: Lucas Gomersall lucas.gomersall@handh.co.uk 07484 082430

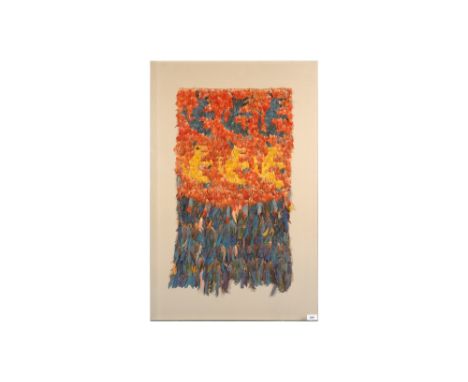

λ A PERUVIAN POLYCHROME FEATHERWORK TABARD FRAGMENT WITH ANIMAL MOTIFS Chimú or Inca Peru, South America, circa 14th - 16th centuryThe rectangular fragment most probably once part of a larger Peruvian tribal tabard garment, made of polychrome bird feathers tied into knots and then knotted directly onto an off-white coarse cotton ground, the feathers prominently in the tones of orange red, light yellow, iridescent teal blue, and brown, the upper section featuring two rows of stylised animals with claws and big fangs, the lower section monochrome, mounted on a cream-coloured cotton canvas in a Perspex casing.The panel 77cm x 43.5cm, 99.5cm x 64.3cm including the frame Provenance: Gifted from the Peruvian Ambassador to the parents of the present vendor in 1968 and in a private UK-based collection since. Exhibited and Published: Juan de Lara, Mestizaje and Craftsmanship in the Viceroyalties of America, Series 'Sumando Historias' of the Museo de America of Madrid, 4 April 2024. The fascination for exotic birds' feathers and their incorporation into artworks, whether in the form of textile panels, totems, adornments, or headdresses, are certainly not only prerogatives of South American civilisations. That said, in the specific case of Peru, featherwork certainly reached an unparalleled high level of complexity and impressive quality during the Chimú (ca. 1000 – 1470) and Inca (1430–1534) periods, as attested by the intricate string system with which the feathers were attached to the tabards. This technique was so elaborate and time-consuming that it is occasionally referred to as 'feather mosaic' (Christine Giuntini in Heidi King, Peruvian Featherworks: Art of the Precolumbian Era, MET, 2012, p. 94). Throughout the 16th century, Spanish and European conquistadors and explorers of the Americas wrote with admiration of the exotic objects they saw on their travels, among them not only clothing and textiles, but also weapons and objects often made of or embellished with rare and precious feathers of birds (Heidi King, Peruvian Featherworks: Art of the Precolumbian Era, MET, 2012, p. 9). Considered symbols of high status, they soon became prized ethnographic possessions, and later entered many important international museum collections. In terms of comparables, our tabard panel presents compositional and manufacturing similarities to another fragmentary panel attributed to Chancay or Ichma Peru, dating 13th - 15th century, in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum (acc. No. VA 660300) (ibidem, p. 33, fig. 21) and another Chimú panel with birds and wave motif, 13th - 15th century, in the Museo Amano, Lima (inv. 7512) (ibidem, p. 118). As far as the decoration goes, birds or animals mixed with running scroll or wave motif were seen on many tabards of the 13th - early 16th-century period, as well as in a variety of other mediums ncluding architecture, ceramics, metalwork. The later dating pieces tend to showcase more abstract and stylised creatures, like the present lot, making species identification difficult. λ This item may require Export or CITES licences in order to leave the UK. It is the buyer's responsibility to find out and conform to the specific export requirements of their country and ensure that lots have the relevant licences before shipping. The panel 77cm x 43.5cm, 99.5cm x 64.3cm including the frame Qty: 1

Twenty three Hard Rock / Heavy Metal / Rock / Blues LPs, mix of UK, USA, Italy, Finland, German and Dutch releases including Faithful Breath Back On My Hill, Windopane See?, Thundertrain Teenage Suicide, Dare Out Of The Silence, Halonen self titled, Dirty Tricks Hit & Run, Uriah Heep Conquest and Innocent Victim, White Sister Fashion By Passion on white vinyl and White Sister, Jerusalem Warrior, Groundhogs Crosscut Saw, Loose Watcher, Bart Rademaker, Smith Minus-Plus, A Foot In Cold Weather All Around Us Trident Studios test press / Emidisc, Solutions It's Only Just Begun, Casablanca, Jonathan Swift, etc

Late 19th century French Zoetrope wheel labelled 'Les Images Vivantes - Petites Tableaux Animes, M. D Paris', together with eleven double sided animation strips including devil in top hat, bell ringing, acrobat, see-saw, huntsman and politically incorrect examples, height 13cm, diameter 22cm

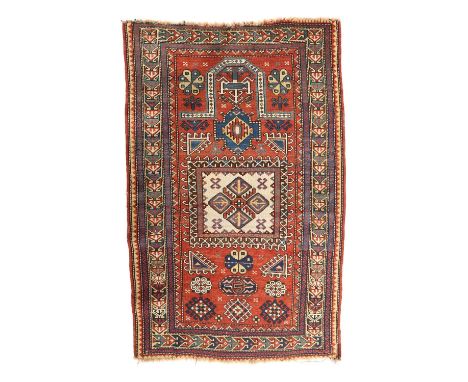

A FACHRALO PRAYER RUGSOUTH CENTRAL CAUCASUS, C.1900the madder field of rosettes and latch hook guls centred by an ivory panel beneath the Mihrab framed by pale lemon borders of polychrome ‘parasol’ devices flanked by 'saw tooth' guard stripes and barber poles169 x 111cmProvenanceThe Hans Joachim Homm Collection.OFFERED WITHOUT RESERVE

A Great War anti-U-boat operations D.S.M. group of three awarded to 2nd Hand J. H. Crumpton, Royal Naval Reserve, who was decorated for his gallant deeds in the Sea King – ex-Q-ship Remexo - in June 1917, when she successfully attacked with depth charges and sank the UC-66 off the Lizard Distinguished Service Medal G.V.R. (SD.3186 J. H. Crumpton, 2nd Hd. R.N.R. “Sea King” English Channel, 12 June 1917); British War and Victory Medals (SD.3186 J. H. Crumpton. 2nd Hd. R.N.R.) mounted court-style for display, nearly extremely fine (3) £1,200-£1,600 (3) £1,200-£1,600 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- D.S.M. London Gazette 31st July 1919: ‘For services in action with enemy submarines.’ Note: Award delayed as destruction of submarine not confirmed until May 1919. Jesse Henry Crumpton was born in Rochester, Kent on 25 June 1883, and enrolled in the Royal Naval Reserve in November 1915. He saw no seagoing service until the following year, when he served in H.M. Trawlers Moray and Lorna Doone, following which, in May 1917, he joined the Sea King (Ex-Q-ship Remexo) under Lieutenant-Commander Godfrey Herbert, D.S.O., R.N.; the latter had already gained notoriety for his uncompromising command of the Q-ship Baralong, not least in her close encounter with the U-27 in August 1915. Of Sea King’s subsequent action against the UC-66 in the Channel on 12 June 1917, Keeble Chatterton’s Amazing Adventure takes up the story: ‘Admiral Luard, the Senior Naval Officer at Falmouth, had received a report that night of a submarine's presence somewhere near the Lizard and ordered Herbert's flotilla off to sea. This sudden alteration of routine, after coming into port and stand-off, was something of a surprise. Men were below taking their well-earned rest and looking forward to a walk ashore in the morning. “I immediately sent a signal to prepare for sea,” Herbert still remembers, “but had some difficulty getting the orders to my friend Buchanan in the Sea Sweeper. After several attempts failed, I fired my revolver at his waterline, which quickly did the trick and we sailed on time.” Through the dark and still summer’s night they all four steamed out past old Pendennis Castle, Helford River’s mouth, the Manacles, and so to the Gaunt Lizard. “We spent a gorgeous middle-watch in perfect weather, and at sunrise I thought to myself how many City workers would have given £10 a minute to be yachting with us.” The dark hours passed, and the dawn of a beautiful day revealed the channel in its kinder mood with shipping going up and down on its lawful occasions. No submarine, however, in sight! Perhaps just one more of those numerous yarns which never came to anything? None the less, you could never be sure, and it was generally supposed that somewhere between the Lizard and Kynance Cove U-boats were fond of going to rest on the bottom. So long as she was down below with engines stopped these four Trawlers would only waste their hours. Besides, the sun had risen, it was time the enemy rose likewise and did something. So Herbert decided to wake him up. “At 4.30 a.m.,” he relates, “I dropped a baby depth charge on a known submarine resting ground not far from Kynance Cove, with the objective of stirring to life any somnolent Hun and incidentally, desiring some fresh fish for breakfast.” During the forenoon, all four trawlers were keeping watch south of the Lizard, listening keenly with their hydrophones. So far nothing had been seen, nothing heard. The Sea King and her sisters seemed to have been brought on a fool’s errand. But at 11.30 a.m. when 2½ miles south east of the headland, “I spotted about 400 yards away, two or three points off my port bow, the periscope, stanchion, and jumper stay of a submarine travelling westward at about 4 or 5 knots. Having seen that stay, I could judge her course much more easily than if only her periscope had been visible. I concluded that her captain had probably just been taking a bearing from the Lizard, and as I turned towards him he dived. At once I hoisted in the Sea King a signal to turn eight points, though this was not taken by all the flotilla. But we all wasted not a second letting-go 16 large depth charges and 64 smaller ones. “It was an exciting moment whilst these were exploding. There was very little time for any signals, and the manner in which the whole flotilla dropped their bombs was admirable. No one could tell exactly where the enemy existed: all I knew was that she lay very near, and it was a barrage which did the trick. Every charge detonated perfectly, all explosions were very heavy, and one sent up water three times the height of any others.” As the tide off the Lizard has, at its maximum, a velocity of 3 knots, a fresh breeze blowing against this soon kicks up a nasty sea. For most of the year there will be found off here a rough tumble of waves and unpleasant jobble: the worst conditions for hydrophone operations. This forenoon, however, the tide was running at about 2 knots to the eastward, and everything remained calm under the favourable weather. To leeward of the enemy there rose up a quantity of oil. The depth charges had beyond all questioning, burst the submarine, set off her mines and torpedoes. Not one German body came to the surface. “The Admiralty instructions,” adds Herbert facetiously, “were very carefully designed to prevent more than one large depth charge being ready at any given moment. Whilst each of us had four, the official orders were that one of these big types was to be ready on deck, but the remainder below unprimed. However, I realized that such levels of precaution were not warranted and, consequently, we all kept our big charges primed and ready “in case”. During the general melee which followed my signal ordering a turn to port, we somehow managed to have one collision, through a helmsman’s misunderstanding, but the damage was very slight. After the sea had regained its calm from the underwater disturbance, we stopped our engines and listened on our hydrophones. It was ideal for hearing any movement, but nothing came through, not a sound reached us. Had she survived, our expert listeners would certainly have detected her under way. The depth at this spot was 40 fathoms, so she could not have rested on the bottom voluntarily. Finally, after hanging about the locality during several hours, we returned to Falmouth, were I reported the affair to Admiral Luard.” Months passed, the Armistice came and went, and at the end of May 1919 - almost two years since the event - an official letter reached Herbert from the Lords of the Admiralty “that it is now known that the submarine in question, UC-66, commanded by Herbert Pustkuchen, was destroyed with the loss of all hands.” This announcement set every doubt at rest, although as a submarine officer himself he had been convinced all the while that the German perished utterly. During the year 1917, Herbert had been at last promoted to Commander, and now for his Lizard victory received a Bar to his Baralong D.S.O. Lieutenant Buchanan was awarded the D.S.C. and two of the crew the D.S.M.’ And one of them was Crumpton, who was demobilised in March 1919.

The superb Second World War B.E.M., American D.F.C. group of six awarded to Wellington and Lancaster Air Gunner Sergeant, later Squadron Leader J. Purcell, 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron, Royal Air Force, who was originally recommended for the George Medal as a result of his gallantry in saving his pilot’s life from a stricken and sinking aircraft off the Suffolk Coast, 2 September 1941, despite suffering from severe burns himself. The latter being Purcell’s introduction to operational flying, and resulting in three days adrift in a dinghy. He qualified for the “Gold Fish Club” again on only his third operational sortie - when his aircraft was forced to ditch off the Norfolk Coast, this time returning from a raid on Emden, 26 November 1941. Purcell went on to take part in the “Thousand Bomber Raids” to Cologne and Bremen, prior to flying with 156 Squadron as part of Pathfinder Force, November 1944 - April 1945. In all he flew in at least 48 operational sorties during the war British Empire Medal, (Military) G.VI.R., 1st issue (1169029 Sgt. Jack Purcell. R.A.F.) contact mark over part of unit; 1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star, 1 clasp, France and Germany; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; United States of America, Distinguished Flying Cross, unnamed as issued, mounted on card for display, generally very fine (6) (6) £2,000-£2,600 --- Provenance: Dix Noonan Webb, December 2007 (when sold without the D.F.C.) B.E.M. London Gazette 6 January 1942. The original recommendation (for a George Medal) states: ‘Sergeant Purcell was the front-gunner of an aircraft which, whilst carrying out an attack on Ostend, received a direct hit from heavy anti-aircraft fire. Although an attempt was made to bring the aircraft back to England, it eventually crashed in the sea some ten miles off Orfordness. On impact the captain was thrown down into the bomb compartment but, after being submerged in 15 feet of water, he eventually escaped, in semi-drowned condition, through the broken off tail of the aircraft. Sergeant Purcell, who was suffering from burns about the face and hands, had helped the captain to climb out of the wreckage and then supported and encouraged him for about half an hour until it was possible to reach the dinghy. In spite of the captain’s continual suggestions that Sergeant Purcell should leave him and get to the dinghy himself, the Sergeant refused to do so. There is little doubt that the captain’s life was saved as a result of the determination and bravery shown by Sergeant Purcell. He subsequently displayed courage, cheerfulness and powers of endurance during the three days which the crew spent floating in the dinghy.’ M.I.D. London Gazette 8 June 1944. United States of America, Distinguished Flying Cross London Gazette 14 June 1946. The original recommendation states: ‘Flight Lieutenant Jack Purcell has displayed exceptional zeal in operations. His first tour of duty was full of hazard and on two occasions his aircraft was forced to alight on the sea, after which this officer spent 74 hours on the first occasion and two hours on the second in his dinghy. He has also been involved on several occasions in combat with enemy aircraft, and on the 16th July 1942, at Lubeck the engagement with two ME 110’s lasted 17 minutes. Other fighters also attacked and a Ju. 88 is claimed as destroyed and a ME 110 was damaged. Flight Lieutenant Purcell has flown on many operations in support of the U.S.A.A.F. and has shown practical co-operation at all times which has proved of great mutual value.’ Jack Purcell was born in Clapham, London in May 1920 and enlisted in the Royal Air Force in July 1940. Qualifying as an Air Gunner in the following year, and having attended No. 11 Operational Training Unit, he was posted to 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron, a Wellington unit operating out of Marham, Norfolk in August 1941. And his introduction to the perils of operational flying were swift, his aircraft being compelled to ditch on his very first sortie, an attack on Ostend on 2 September 1941. 218 Squadron’s Operational Record Book gives further detail: ‘Nothing was heard from this aircraft after it left base. The entire crew were posted as missing. Later it appeared that the aircraft had come down in flames over the sea, nose first, as a result of being hit off Ostend. The pilot’s cockpit was about ten feet under water, the only part of the aircraft not on fire. Squadron Leader Gibbs, D.F.C., struggled to get out of the pilot’s escape hatch but it was jammed. After various things seeming to fly past him and very weak as a result of trying to hold his breath in between the intervals of taking in water, he found he was too weak to open the astro hatch when he located it. Eventually, after what seemed like an age, he found a break in the fuselage, where the Sergeant Front Gunner [Purcell] was just getting through. They struggled out and the Sergeant tried to blow up the Squadron Leader’s flotation jacket with his mouth, but he could not manage it. The Squadron Leader cannot remember getting into the dinghy, his only memories being an endless moment in which he had his head under water for what seemed like an eternity. For three days and nights the crew drifted. On the first morning they heard a bell buoy, but the tide swept them past it. They rationed their supplies. On the third day they could see buildings and could hear trains but they were still being washed in and out by tides. Eventually, they were washed ashore near Margate. For four of the crew, including the Front Gunner, this was their first operational flight. It was Squadron Leader Gibbs’ 36th raid.’ No doubt as a result of the burns he sustained, Purcell did not fly again until 4 November 1941, when he was once more detailed to attack Ostend. Then on the 26th of that month, in a raid against Emden, in Wellington Z.1103 A, piloted by Sergeant Helfer, he had the unhappy experience of a second ditching. 218’s Operational Record Book again takes up the story: ‘Bombed Emden, 10th/10th cloud, N.A.P. sent. Flak from Islands when returning. A fuel check was taken by the Navigator, the gauges showing 130 gallons in tanks. D./R. position from coast - 100 miles. In 15 minutes the loss of 50 gallons showed on the fuel check, now only 80 gallons in tanks. As the coast was not reached by E.T.A., the captain decided to come down to 3,500 feet. The aircraft flew at this height for some while and not seeing coastline the captain asked for a priority fix at 10.21 hours. This showed him to be 100 miles from the coast. The nacelle tanks had been pulled on some 20 minutes before the prioriy fix was received. The W./T. receiver was now U./S and no bearings could be received, but the transmitter could be used and so an S.O.S. was sent at 22.30 hours, as it appeared doubtful whether it would be possible to reach the coast. The coast was reached at 10.55 hours and searchlights pointing west along the coast were seen and a green Very light was fired from the ground. We turned west and flew along in the direction of the searchlight. The engines started spluttering and the captain decided to land on the water as near the coast as possible. The reason the captain decided not to land on the beach was because of the possibility of it being mined - and it was! Prior to landing on the sea the containers were jettisoned and the flotation bags pulled. The dinghy inflated automatically. The aircraft sank within five minutes. All of the crew successfully got into the dinghy and cut it adrift with the knife provided. Immediately one marine distress signal was let off. The crew drifted for about two hours. The crew then saw a light flashing on the w...

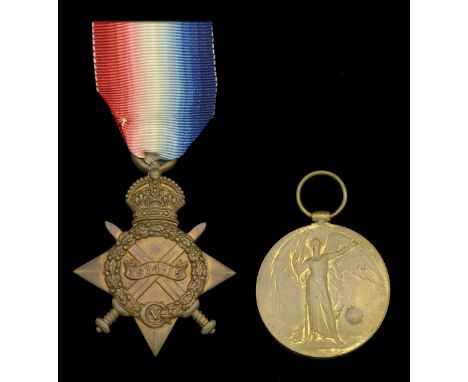

1914-15 Star (Pte. F. H. Somerset Kimberley Cdo.); Victory Medal 1914-19 (Capt. N. H. Moore.) very fine and better (2) £80-£100 --- Francis Henry Somerset was born on 5 September 1882 and having emigrated to South Africa served briefly with French’s Scouts during the latter stages of the Boer War (entitled to a Queen’s South Africa Medal with clasps for Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal, and South Africa 1901). He saw further service during the Great War, initially with the Kimberley Commando in German South West Africa in 1915, before proceeding to England as part of the 1st South African Brigade. He served with them in Egypt, and then, having been commissioned Second Lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment, South African Infantry, saw further service on the Western Front. Somerset distinguished himself during the epic action at Delville Wood on 18 July 1916, and was praised in a letter written by Captain Richard Medlicott, commanding ‘B’ Company, 3rd Regiment: ‘The bombardment was intense all day, and our fellows and a platoon of the 4th Regiment dug themselves in. Suffering from want of food and water, and with the wounded impossible to get away, D Company retired without passing up any word, so did those on their left. My Orders were to hold on. I was on point of salient and furthest force pushed out. A and C Companies on my right not being dug in were scattered - 1 platoon of D Company under Second Lieutenant Somerset did well on my left. I used 4th Regiment in reserve trench as reinforcements. Ammunition scarce. Mud caused ammunition to be useless as rifles jammed with mud. No cleaning material - all consumed. Two guns, one Lewis and one Maxim knocked out. Our own field guns killed and wounded many of us. Difficulty owing to this to extend to my left. D Company retired when the attack came at probably 5pm or later; however, beat Germans off. Many killed seven yards from my trenches. Remnants of A and C Companies overpowered... I learnt this after heat of attack abated, with machine-guns enfilading us from my right. By passing up five rounds at a time from each man I kept machine-guns and one Lewis gun going sparingly and killed many Germans. I divided my front i.e. alternate men facing alternate fronts. Sent bombing party and patrol under officer to try and clear my right and get away to retire to Waterlot Farm or our old regimental headquarters.’ Somerset was subsequently killed during the Battle of Delville Wood, his date of death officially recorded as 20 July 1916, the day the Brogade was relieved. He is buried in Delville Wood Communal Cemetery, France. Sold with copied research. Norman Hope Moore was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment, before transferring to the 3rd Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, on 1 December 1908. Appointed Instructor of Musketry on 1 January 1909, he was mobilised on the outbreak of the Great War, and served with the 2nd Battalion during the Great War on the Western Front from September 1914, commanding ‘A” Company for a short period. Wounded at the Battle of the Aisne, he was invalided home at the end of October 1914, during the first Battle of Ypres, and subsequently rejoined the 3rd Battalion, serving with them at home for the remainder of the War. He subsequently compiled the Battalion History, Records of the 3rd Battalion, the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment, Formerly 6th West York Militia, 1760-1910’. He died on 8 March 1938. Sold with copied research.

A Second War ‘North Africa operations’ C.B.E. group of nine awarded to Brigadier L. F. Heard, Royal Engineers, who was Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the French Croix de Guerre for his services in North West Europe, and subsequently served as Aide-de-Camp to H.M. the Queen, 1954-57 The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, C.B.E., (Military) Commander’s 2nd type neck badge, silver-gilt and enamel, with neck riband, in DS & S case of issue; India General Service 1908-35, 1 clasp, North West Frontier 1930-31 (Lieut. L. F. Heard. R.E.); 1939-45 Star; Africa Star, 1 clasp, 1st Army; France and Germany Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; Coronation 1953, unnamed as issued; France, Third Republic, Croix de Guerre, bronze, reverse dated 1939, with bronze palm on riband, mounted court-style for display, light contact marks, good very fine and better (9) £600-£800 --- C.B.E. London Gazette 1 January 1943 M.I.D. London Gazette 22 March 1945: ‘In recognition of gallant and distinguished services in North West Europe.’ The original Recommendation for the French Croix de Guerre states: ‘This officer has been General Staff Officer First Class at 21 Army Group Headquarters since its formation. He is an extremely capable Staff Officer with a unique knowledge of staff duties and of the organisation of the Army. His services have been extremely valuable during the planning and execution of the operations for the liberation of France, and he has never failed to give off his best in spite of the pressure of work which has been acute during the period under a view.’ Leonard Ferguson Heard was born on 30 October 1903 and was educated at Shrewsbury School and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He was commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers on 29 August 1923, and saw active service on the North West Frontier of India as a Staff Captain, R.E., attached Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners. Advanced Major on 29 August 1940, he saw further service during the Second World War, both in North Africa, for which services he was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and subsequently in command of 23rd Assault Group, Royal Engineers, in North West Europe, for which services he was Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the French Croix de Guerre with palm. Promoted Colonel in 1947, and Brigadier in 1949, Heard was appointed Aide-de-Camp to H.M. Queen Elizabeth II on 30 December 1953, relinquishing the appointment on his retirement on 21 April 1957. He was lucky to survive a train crash in 1959 when his car was struck by the Belfast to Londonderry express train at 65 miles per hour, whilst he was driving across an unmanned level crossing; the force of impact somersaulted the diesel engine off the track and derailed several carriages, but remarkably both he and all the passengers on the train survived virtually unscathed. He was subsequently sued by the Ulster Transport Authority. Advanced Honorary Major-General on the Retired List, he was appointed High Sheriff of County Londonderry for the year 1964, and also served as a Justice of the Peace. He died on 8 April 1976. Sold with a photographic image of the recipient, and copied research.

Five: Signalman J. E. Saunders, Royal Signals, who died of wounds on Malta on 27 June 1940 General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Palestine (2325411 Sgln. J. E. Saunders. R. Sigs.); 1939-45 Star; Africa Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, very fine (5) £120-£160 --- John Ernest Saunders attested into the Royal Signals and served in pre-War Palestine. He saw further service during the Second War with Malta Infantry Brigade Signals and died of wounds on the island on 27 June 1940, most likely received during an earlier air raid. He is buried in Pieta Military Cemetery, Malta. Sold with copied medal roll extracts, copied casualty list and copied entry from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission register.

New Zealand 1845-66, reverse dated 1861 to 1866 (2034. Danl. Mc.Namara, 2nd. Bn. 14th. Regt.) lacquered, contact marks, nearly very fine £300-£400 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Daniel McNamara was born in Dartford, Kent, in 1830, and attested for the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot on 8 March 1843, aged 14. Initially serving in the United Kingdom, he was later deployed to Australia, arriving in the Australian colonies in 1852, and it is recorded that, as a member of the 40th Regiment band, he played at the Grand Military Harmonic Society concert in Geelong, Victoria on 5 June 1860, playing the trombone. McNamara served with the 40th Regiment of Foot in New Zealand from 24 July 1860; the Band of the 40th were conveyed to shore in surf boats and, with some difficulty, played themselves ashore in the boats! He went on to serve for a period of 6 years and 83 days in New Zealand; during this time, the regiment participated in the major Taranaki battles of 1860-61, held garrison in Auckland on various occasions, collaborated with other regiments in constructing the Great South Road towards the Waikato in 1861-2, and engaged in several significant Waikato battles of 1863-64. He transferred to the 2nd Battalion, 14th Regiment of Foot, on 1 June 1866 whilst still in New Zealand, and was subsequently awarded a Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. He was discharged in Australia on 28 June 1870, after 23 years and 113 days’ man’s service, and died in Melbourne, Australia, on 7 November 1900, aged 70. Note: McNamara should have been issued an undated New Zealand Medal named to the 40th Regiment of Foot, owing to the fact that he was an inter-Regimental transfer whilst in New Zealand, and would thus be shown as non-effective on the roll of the first Regiment with which he served in New Zealand. Instead, he is shown on the medal rolls of the 2/14th Regiment of Foot, and interestingly the medal he was issued bears the dates that the 2/14th saw active service in New Zealand (1861-66), and not the dates that McNamara presumably saw active service in New Zealand (1860-66).

Four: Company Sergeant Major L. Cotterell, Herefordshire Regiment 1914-15 Star (2121 Pte. L. Cotterell. Hereford. R.); British War and Victory Medals (2121 Pte. L. Cotterell. Hereford. R.); Efficiency Medal, G.V.R., Territorial (4103561 W. O. Cl. II. L. Cottrell. [sic] Hereford. R.) contact marks, some verdigris stains, very fine British War Medal 1914-20 (1-8186 Pte. T. Hegarty. R. Ir. Rif.) edge bruise, nearly very fine (5) £180-£220 --- Leonard Cotterell attested into the Herefordshire Regiment and served at Gallipoli with the 1st Battalion, landing at Suvla Bay on 9 August 1915. He saw further service with the Welsh Regiment in Egypt before rejoining his old regiment and was discharged on 7 April 1919. Reenlisting into the Herefordshire Regiment (Territorial Army) on 22 July 1921, he was advanced Company Sergeant Major and awarded the Territorial Efficiency Medal. Sold with copied research. Thomas Hegarty, from Dublin, attested into the Royal Irish Fusiliers and served during the Great War on the Western Front with the 1st Battalion from 6 November 1914. Advanced Sergeant, he was killed in action on 9 May 1915 and is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial, Belgium. Sold with copied research.

A Second War ‘Minesweeping’ D.S.C. group of seven awarded to Skipper A. A. Hindes, Royal Naval Reserve Distinguished Service Cross, G.VI.R., reverse officially dated ‘1941’, hallmarks for London 1940; 1914-15 Star (DA. 899 A. Hindes, D.H. R.N.R.); British War and Victory Medals (899DA A. Hindes. D.H. R.N.R.); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; War Medal 1939-45, together with Mine Clearance Service white metal arm badge, this with two lugs but lacking back plate, and R.N.P.S. lapel badge, good very fine (9) £1,000-£1,400 --- D.S.C. London Gazette 1 July 1941, Birthday Honours List: ‘Temporary Skipper Alfred Augustus Hindes, 311 T.S., R.N.R.’ Alfred Augustus Hindes was born at Lowestoft on 6 March 1894, and prior to the outbreak of the war was working on fishing trawlers out of Lowestoft as a Deck Hand. Having joined the Royal Naval Reserve he was immediately called up on 10 August 1914 for minesweeping services as a Deck Hand. He served aboard various trawlers and drifters and by the end of the war was based at Ganges, a Minesweeper Trawler base, from where he was demobilised on 26 January 1919. In February 1919 Hindes joined the newly formed Mine Clearance Service for which he subsequently was awarded the arm badge. The outbreak of the Second World War saw him called up and appointed Temporary Skipper on 9 January 1940, and promoted to Skipper by August 1940 when he joined H.M. Trawler Sunlight, operating out of Queensborough Pier, near Sheerness, known as H.M.S. Wildfire II which in July 1941 became H.M.S. Tudno. This came under Nore Command which covered the North Sea from Flamborough Head to North Foreland and across to the enemy held coastline. Sunlight twice had her bows blown up by acoustic mines in the early days before a method was devised to explode the mine further ahead of the ship. He left Sunlight shortly after February 1943 after the vessel had been attacked by E boats and aircraft, limping into Aberdeen where she was paid off. He was then Skipper of the trawler Charles Dorian, based at H.M.S. Miranda, Great Yarmouth, sweeping the channels and escorting convoys up the East Coast as part of the 13th Minesweeping Group. She was paid off in Glasgow in June 1945, when Hindes was also demobilised. He died on 30 July 1966, at Kelling, near Holt, Norfolk, and is buried in Lowestoft Cemetery. Sold with copied research.

Three: Warrant Officer Class II G. Gilmour, Rifle Brigade Queen’s South Africa 1899-1902, 3 clasps, Cape Colony, Tugela Heights, Relief of Ladysmith (6239. Pte. G. Gilmour. Rif. Brig.) engraved naming; British War Medal 1914-20 (6239 A.W.O. Cl. 2 G. Gilmour. Rif. Brig.); Army L.S. & G.C., G.V.R., 1st issue (6239 C. Sjt: G. Gilmour. Rif: Bde:) mounted court-style for display, minor edge bruise to first, generally very fine and better (3) £200-£240 --- George Gilmour was born on 6 January 1879 and attested for the Rifle Brigade on 6 October 1898. He served with the 1st Battalion in South Africa during the Boer War. An Orderly Room Clerk for much of his service, he was advanced Acting Warrant Officer Class II and and saw further service during the Great War with the 6th Battalion on Draft Conducting Duties (entitled to a British War Medal only). Awarded his Long Service and Good Conduct Medal on 1 July 1917, the following year he was appointed Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant of the 2nd Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Volunteer Battalion. He was discharged on 24 July 1921, and saw further service during the Second World War at the Recruiting Office in Southampton. He died in Parkstone on 1 August 1963. Sold with a photographic image of the recipient, medal roll extracts, and copied research.

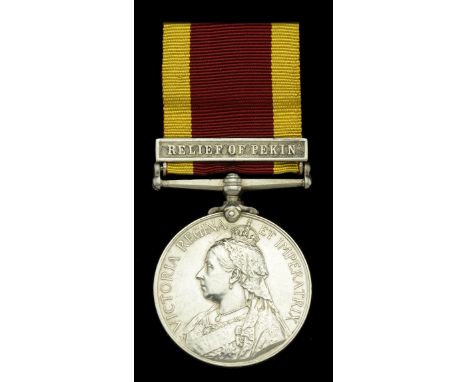

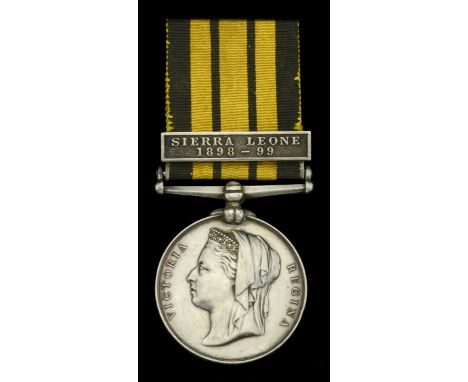

China 1900, 1 clasp, Relief of Pekin (F. Rixon, A.B., H.M.S. Endymion.) minor edge bruise, good very fine £260-£300 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Dix Noonan Webb, December 2007. Fredrick Rixon was born at Boldre, Hampshire, on 28 February 1880, and joined the Royal Navy as a Boy Second Class on 8 May 1895. He was posted to the cruiser H.M.S. Endymion in June 1899, and saw active service during the Boxer Rebellion, serving as part of the Seymour Expedition that took part in the Relief of Pekin. Advanced Able Seaman on 1 October 1900, he saw further service in a variety of ships and shore based establishments, and was promoted Leading Seaman on 1 March 1906. Rixon’s naval career was frequently punctuated by periods in the cells, and his Royal Naval career came to an end on 7 December 1908, his service papers recording ‘Run, H.M.S. Essex, Portsmouth, 7.12.08’. He was subsequently employed in the Merchant Navy.