We found 84901 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 84901 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

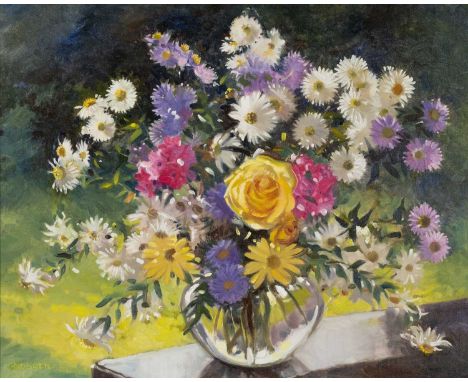

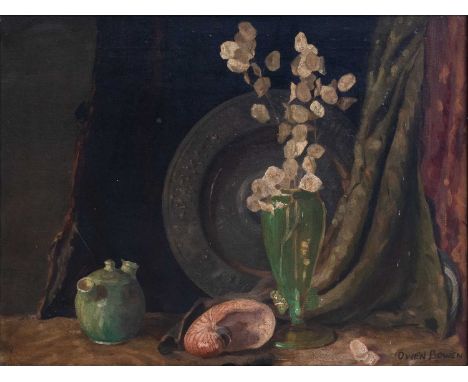

‡GERALDINE MARY O'BRIEN (Irish, 1922-2014) oil on canvas - still life flowers in a glass vase, signed, 39 x 49.5cmsProvenance: private collection Vale of GlamorganAuctioneer's Note: Geraldine O'Brien was an Irish botanical illustrator, and daughter to Cicely Maud Carus-Wilson a distinguished artist. She was cousin to both the artist Dermod O'Brien PRHA and President of the Watercolour Society Kitty Wilmer O'Brien RHA. Her studio in Limerick was always called 'The Piggery' and was where she brought the plants from her garden in to arrange for her work. She continued to exhibit on a regular basis both with the RHA and private exhibitions around Ireland. Comments: framed, ready to hang

Assorted Costume and Accessories, Pictures, Ephemera, including hats, scarves, ties, handbags (including Guess), white gown by Donerica, gent's black suit, ladies blouses, hats and fascinators, a quantity of table linen, fabric remnants etc, together with a modern still life oil on board in gilt frame, a watercolour of sheep on a rocky edge by M Anderson, and various volumes of early 20th century Graphic Magazine and London Illustrated News (qty)

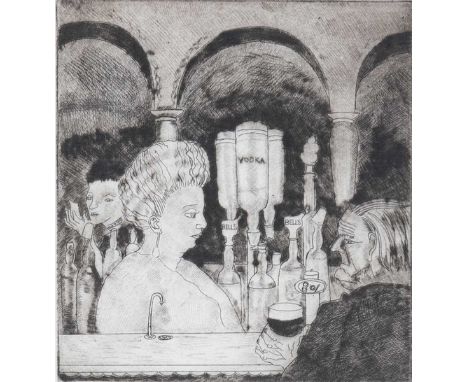

Michael McVeigh (b.1957) Scottish"Cafe Royale"Signed and numbered 15/20, etching, 36cm by 28cm overall; together with a 20th century still life of fruit and flowers on a table, indistinctly signed and inscribed, possibly by Rodger Massacry, pen; together with two 20th century figurative pencil sketches, one initialled E. V., the other indistinctly inscribed (4)

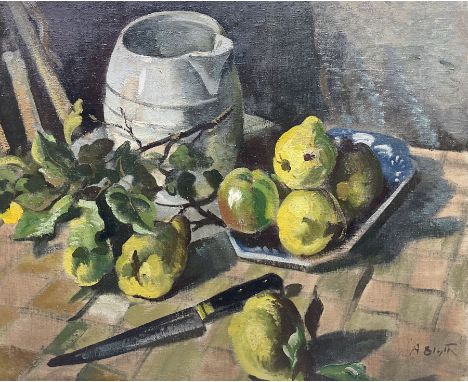

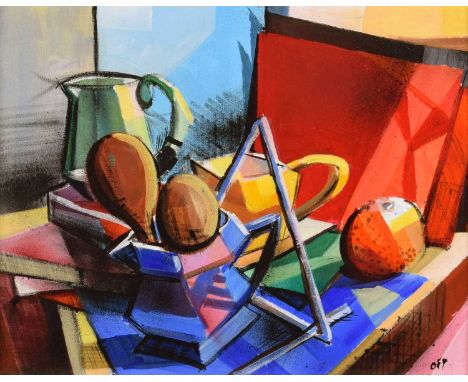

Olivia Pilling (British 1985-) "Still Life with Blue Jug" Initialled, acrylic on canvas board.23.5 x 29cm (framed 41 x 45.5cm)Artists’ Resale Right (“droit de suite”) may apply to this lot.The painting is in very good, original condition with no obvious faults to report. The painting is ornately framed but not glazed. The frame has some minor scuffs and knocks commensurate with age.

Olivia Pilling (British 1985-) Still Life Initialled, acrylic on board.34.5 x 44.5cm (framed 47 x 57cm)Artists’ Resale Right (“droit de suite”) may apply to this lot.The painting is in very good, original condition with no obvious faults to report. The painting is ornately framed but not glazed. The frame has some minor scuffs and knocks commensurate with age.

The rare and superb 'Operation Grapeshot' M.B.E., 'Monte Rogno' Virtuti Militi, 'Monte Cassino' Cross of Valor group of nine awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel T. Lipowski, 9th Heavy Artillery Regiment, Polish Army, whose remarkable life story includes a tragic episode during the Fall of Poland which saw him narrowly escape the fate of two of his comrades, who were arrested and murdered during the Katyn MassacreReturning to active service his extreme bravery attached to the 5th (Kresowa) Division in Italy saw him honoured on several occasions and even wounded during the Battle of Monte Cassino, being hit by shrapnel that had already passed through the lung of a brother Officer who stood besidePoland, Republic, Order of Virtuti Militari, breast Badge, 5th Class, silver and enamel, of wartime manufacture by Spink; Cross of Valor, with Second Award Bar; Cross of Merit, with swords, 2nd Type, silver-gilt; Army Medal; Monte Cassino Cross 1944, the reverse officially numbered '33078'; United Kingdom, The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, 2nd Type, Military Division, Member's (M.B.E.) breast Badge, silver; 1939-45 Star; Italy Star; Italy, Kingdom, Croce al Valore Militare, sold together with an archive including a named cigarette case, portrait and photograph album and the named document of issue for the award of the M.B.E., overall good very fine (9)Virtuti Militari awarded 30 June 1944, the original citation (translated) states:'During the operations 'Adriatyk', he distinguished himself by working in difficult conditions under strong and accurate enemy fire, especially at the Observation Point on Monte Regano. He cooperated perfectly with the infantry, conducting accurate and effective fire, not breaking off observation despite the fire. With his behaviour, he set an exemplary example for officers and privates at the Observation Points, as always. He fully deserves the decoration.'Cross of Valor awarded 6 August 1944, the original citation (translated) states:'At Cassino he organized an Observation Point and stayed there. On May 10-12, 1944, despite heavy enemy mortar and artillery fire, he remained at the Observation Point and continued his work. On May 12, 1944, despite heavy fire, he left the Observation Point to get better information and moved forward. He was wounded, but he did not want to stop his work.'Second Award Bar awarded 1945.M.B.E. London Gazette June 1945, the original recommendation states:'During the period 9th -21st April 1945, this officer worked with the maximum devotion as B.M., F.A. 5th Kresowa Division Artillery, which was in support of the Infantry in their operations against lines of Rivers Senio, Santerno, Sillaro, Gaina and Idice. Major Lipowski made a particularly great effort and showed special dexterity on 19th April and night 19th/20th, when Headquarters 5th Kresowa Division was faced with the task of co-ordinating the fire plans not only of the Divisions Artillery but also Artillery under command of the neighbouring RAK Force (Reinforced 2 Polish Armoured Brigade with 2 British Royal Horse Artillery and 3 Polish Field Regiment in SP). Rud Force (3rd and 4th Polish Infantry Brigades supported by 5th Polish Field Regiment and 7PHA) and AGPA.Major Lipowski's skillful [SIC] Staff work at HQ 5th Kresowa Division Artillery on 19th April and night 19th/20th resulted in the rapid working out and co-ordination of the Artillery fire plans which effectively helped the Infantry and assisted the Armour in breaking down enemy opposition, crossing the Gaina River and approaching River Quaderno.The Staff work at HQ 5th Kresowa Division Artillery had to be completed in a limited time in order to prepare the above Artillery plans and called for great effort and extreme accuracy. Major Lipowski not only directed the Staff work most efficiently but shone as an example of adroitness and devotion to duty.'Note the number of the recipient's Monte Cassino Cross is confirmed upon the roll.Tadeusz Lipowski was born on 29 March 1904, the son of two flour mill owners. His parents were forced to produce food for the German Army during the Great War, whilst the young Lipowski attended the local grammar school. Joining the Infantry Cadet School in 1926 he transferred to the Artillery Cadet School the next year and was commissioned Lieutenant in 1929.September 1939 and escaping to fight againPosted to Bendzen, Lipowski was set to work training new recruits, he was still there when the German Army invaded Poland in September 1939. His Regiment was left in an exposed position and forced to withdraw to avoid being encircled.Lipowski was interviewed post-war and the interviewer wrote a summary of his experiences, this narrative takes up the story:'The regiment was soon split up and within three days it had been officially annihilated although splinter groups had joined other regiments to continue fighting. Tade was able to join the Le Wolf East Polish soldiers on the 21st September and together they had fought their way out of danger or so they thought. Similar situations repeated themselves throughout Poland where the soldiers fought bravely on their own without the support of their planes which had been destroyed during the first day and without the aid of advanced weaponry…'Not long later the Russians invaded as well, tightening the noose around the Polish Army, communications at the time meant that many soldiers were not even aware of the Russian attack. One of these was Lipowski who awoke in a wood one morning to the sight of a Russian soldier on patrol. Unsure of whether this man was a friend or foe he remained hidden as the unsuspecting Russian passed beneath his sights, it was not until later that he discovered how close he had come to disaster.As the Polish defences were overrun, the Regiments began to splinter in small groups either seeking to withdraw to France and carry on the fight or set up resistance organisations. Lipowski, accompanied by two brother Officers, returned to the town in which he had been at school. His sister was living in the town and while they planned their next step she concealed them in her home.His brother came up with a plan to move them to a safer location by dressing the three men in his suits and putting them in the back of a wagon driven by a friendly farmer. Lipowski was forced to borrow a suit by his brother however the two Officers with him refused as the suits were expensive and they didn't want to take them. Instead, they removed their rank pips and took on the appearance of other ranks.During the journey the travellers were stopped by a Russian soldier, the farmer attempted to explain away the soldiers in his cart however this was for naught:'The Colonel could remain silent no longer and admitted to the Russian that they were in fact Officers so that the farmer would not get into trouble. Tadek said nothing but looked straight ahead. These Officers were only two of the many who were shot at Katyn by the Soviet secret police and left to rot in the mass grave, later discovered and dug up by the Germans two years later. Tadek had once again narrowly escaped death by what he called "good luck".' (Ibid)Reaching an underground resistance organisation, Lipowski was concealed by them and on 25 December 1939 dressed as a civilian he set out for southern Poland and the border. At one point he was stopped by a German soldier and asked when he was going, for one heart stopping moment it seemed that he was caught. This was not the case however, and it turned out the German was drunk and looking for someone to share a beer with - Lipowski agreed to a drink and later the soldier even waved him off on the tr…

An Escaper's campaign group of four awarded to Sergeant W. H. Price, 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, later Military Provost Staff Corps, who was wounded and went 'in the bag' at Tournai in May 1940 only to escape from Stalag VIII-BGeneral Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Palestine (3653478. Pte. W. H. Price. Bord. R.); 1939-45 Star; War Medal 1939-45; Army L.S. & G.C., Regular Army, E.II.R. (3653478 Sgt. W. H. Price. M.P.S.C.), mounted as worn, the retaining pin missing, light pitting and contact wear, very fine (4)William Herbert Price was born on 15 June 1919, the son of Isaac Price and a native of St. Luke's Avenue, Lowton, Golborne. Enlisting with the Border Regiment on 3 October 1936 he was stationed with the 1st Battalion when they in Palestine prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, returning to Britain in April 1939.Posted to France in December 1939 they were stationed on the frontline during the Phoney War and were at the front of the British advance into Belgium prior to the Ardennes Offensive in May 1940. As such they were still in Belgium when they engaged the German advance at Tournai on 20 May. They held out for that day and into 21 May however lost some ground on the second day, which is the day that Price is listed as slightly wounded and taken prisoner of war. His service papers note details of his interrogation after his capture in response to the question was, he interrogated he states:'Yes. In a wood S Tournai, May 1940 […] soup with promise of good meal & cigarettes.'It seems that Price was the subject of a gentle interrogation then despite this he was unfortunate to be taken when he was. The next day reinforcements in the shape of 1/6th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers retook the lost ground whilst the Borderers were pulled back and eventually evacuated.Price was taken initially to Marienburg and later Thorn like most British prisoners from France he was transferred to Stalag 11-B in April 1941 and from there to Stalag VIII-B at Lamsdorf. Whilst there he worked in a saw mill it was from here that he attempted his escape, noting that he and two comrades -Corporal W. B. Wren and Private Kennel- slipped out at night from the shoemakers in the camp.Unfortunately, there were retaken '…by German police man assisted by German Pole', apparently at the time Price was unfit, suggesting that they had struggled with life on the run. He also noted attempted sabotage during the attempt, they tried to damage some railway signalling equipment however this seems to have been unsuccessful.A newspaper article of the time notes that his father believed him dead in France and had held a memorial service for him. Fortunately before a planned memorial could be erected the British Red Cross informed him that his son may be alive. Price remained in the Military after the war, going on to join the Military Provost Staff Corps, responsible for staffing British Military Prisons; sold together with copied research.…

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant'After some delay...a letter was received on Tuesday from Sir George explaining that the claim of the old Peninsular veteran had been doubly recognised; with the sanction of H.R.H, the Queen has been informed through Sir Henry Ponsonby of Captain Gammell's case, and Her Majesty was so interested in it that she decided to present to the veteran her Jubilee medal, in addition to the Peninsular medal...Those who know what a staunch supporter of the Throne and Constitution he has always been, as well as a brave officer in his younger days, will heartily congratulate him on the double honours he has received, especially his kind recognition by the Queen' (Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette, Thursday 28 September 1893, refers)The historically fascinating and unique Peninsular War and Queen Victoria Jubilee pair awarded to Captain J. Gammell, late 59th, 92nd and 61st regiments of Foot, who was almost certainly the last surviving British Officer of the Peninsular War and who claimed his campaign Medal in 1889 - an astonishing 75 years after the battle in which he participated and such a remarkable circumstance that The Queen herself then commanded that he should also be awarded her Jubilee MedalMilitary General Service 1793-1814, 1 clasp, Nive (Ensign, James Gammell. 59th Foot.), this officially named in the style of the Egypt and Sudan Medal 1882-89; Jubilee 1887, silver, unnamed as issued, mounted together upon a silver bar for wear, on their original ribands and contained within a bespoke fitted leather case by Mallett, Goldsmith, Bath, the top lid tooled in gilded letters stating: Presented by Command of Her Majesty Queen Victoria to Capt. James Gammell, late 92nd, 61st and 59th Regiments, when in his 93rd year, 9 March 1889., traces of old lacquer, otherwise about extremely fine (2)James Gammell, second son of Lieutenant-General Andrew Gammell and Martha Stageldoir, was born in London on 3 January 1797. Scion of an old Scottish family, his father enjoyed a long (if undistinguished) military career and appears to have been a personal friend of H.R.H. the Duke of York; it is he who may have been responsible for the elder Gammell's appointment to the socially-prestigious 1st Foot Guards in September 1803.On 29 September 1813, young James Gammell was commissioned Ensign (without purchase) in the 59th (2nd Nottinghamshire) Regiment of Foot (London Gazette, 2 October 1813, refers). The 2nd Battalion of the 59th had already seen its fair share of active service during the Napoleonic Wars, having been in Spain in 1808 and 1809 before being re-deployed on the disastrous Walcheren Campaign. Returning home, in 1812 the unit was sent back to the Iberian Peninsula where they participated in most of the final battles of that campaign including Vittoria (June 1813); Nivelle (November 1813) and the Nive (December 1813). Gammell clearly must have joined his regiment in the summer or autumn of that year, as his single-clasp Medal attests; for his first (and indeed only) major battle he must have seen a significant amount of fighting as the 59th suffered casualties of some 159 men killed and wounded. The regiment returned home at the conclusion of hostilities, and Gammell is next noted as being promoted into the Sicilian Regiment on 27 April 1815 (London Gazette, 6 May 1815, refers).Remaining in the peacetime Army, like many young junior officers Gammell moved through several different units over the next few years. The Sicilian Regiment may have offered the chance for some interesting soldiering, but it is unlikely he ever spent time with them as on 1 June the same year he transferred (still as Lieutenant) into the 61st (South Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot. Likely with them on garrison duty in Jamaica from 1816-22 on 21 August 1823 he moved again, this time to the 64th (2nd Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot - but again still as a Lieutenant. In 1825 he was promoted to Captain in the 92nd (Gordon Highlanders) by purchase (London Gazette, 14 May 1825, refers) - but yet again he was not destined to remain long in his regiment as a mere five months later the London Gazette carries another entry (dated 22 October) stating that he had retired on 6 October that year.It is quite likely that, in reality, Gammell had no need to be a soldier as he was an independently wealthy man. In 1816, soon after his father's death, his grandfather purchased an agricultural estate for him and, though the two were later to fall out over the subject of Gammell's marriage to a Miss Sydney Holmes, the estate ensured he was to receive a steady source of income for him and his family for the rest of his life. Marrying Miss Holmes on 21 September 1825, the couple went on to have no less than ten children and in 1834 the Gammell family moved to Edinburgh before relocating to Bath in 1856-57 and taking up residence at 16 Grosvenor Place. Here Gammell was to remain until his death on 23 September 1893 at the remarkable age of 96, which makes him quite likely the last surviving British officer to have participated in the Peninsular War - a fact supported by several primary and secondary sources, the latter including a reference in the Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society (March 2009) and the book Wellington's Men Remembered: A Register of Memorials to Soldiers who Fought in the Peninsular War and at Waterloo. He was interred at Locksbrook Cemetery, Bath, and the occasion included his coffin being conveyed to the site in a closed hearse, covered in a Union Jack, and a wreath stating: 'In kindly remembrance of the last of the Peninsular officers.'However, his story does not end here, as just a few years previously he became the subject of a remarkable tale which led to the award of two medals - the first of which he had earned as a 17-year-old Ensign in the 59th Foot all those years ago. The 'Bath Chronicle' takes up the story:'Captain James Gammell, the only surviving officer of the British Army which fought in the Peninsular War, died on Saturday last at 16, Grosvenor Place, Bath, where he had resided for many years...By his death the work of charity in the neighbourhood of Larkhall loses a generous friend, the Conservative cause one of its most ardent supporters, and the Queen one of the most loyal and devoted of her subjects. His loyalty and attachment to her Majesty was one of the dominant features of Captain Gammell's character and his enthusiasm was evidenced during the celebration of the Royal Jubilee in 1887. Flags were liberally displayed at his residence, and the letters "V.R." in gas jets, with a shield bearing the Royal arms, and the motto "Tria in juncta uno - Quis separabit." ...In March, 1889, the Bath Chronicle thus described how Captain Gammell received the Peninsular medal and the Queen's Jubilee medal: -A curious and gratifying incident has just occurred, which for the credit of all concerned is worth recording. At the latter end of December Colonel Balguy happened to be at the National Provincial Bank, and a casual remark made by him led a venerable gentleman near to say that it was just 75 years ago that he donned the red coat. Surprised at the communication, Colonel Balguy rejoined "You must have been in the Peninsula." "I was at Bayonne in 1814, when the French made their sortie," replied the stranger. "Then you have a medal?" He explained that he never had one nor had he applied for one, and in reply to further questions, stated that he was an Ensign in the 59th Regiment, and retired as a Captain from the Gordon Highlanders in 1825. The conversation again turned upon the medal, and after some hesitation he accepted Colonel Balguy's o…

The 'St. Pancras bombing 1941' B.E.M. awarded to Constable H. J. Smith, Police War Reserve, 'N' Division, Metropolitan Police who, whilst off duty, saw a women trapped in her home by a parachute mineFinding a ladder he climbed the crumbling, bomb damaged building, dug her free and pulled her to safety, all while the bombs continued around him, his original recommendation was for the George Medal, later downgradedBritish Empire Medal, Civil Division, G.VI.R. (Henry John Smith), officially engraved naming on a pre-prepared background, light edge wear, very fineB.E.M. London Gazette 12 September 1941, the original citation states:'A bomb damaged a building, the remains of which were liable to collapse. War Reserve Constable Smith obtained a ladder, climbed to the top of it and then hauled himself on to a balcony which went round to the first floor. He climbed through a window and entered a room where he found a woman buried up to the neck in rubble. He began to dig with his hands although debris was falling and further bombs were dropped in the neighbourhood. Smith eventually released the victim and carried her to safety.'Henry John Smith worked as a packer in civilian life and was living at 41 Goldington Buildings, St. Pancras during the Second World War. He volunteered for the Police War Reserve and was posted to 'N' Division, Metropolitan Police. The original recommendation for his award was for the George Medal however it was downgraded to the B.E.M., the text goes into further detail on the events of 17 April 1941:'On 17th April 1941 at about 3.15 a.m. a parachute mine fell in Pancras Square, Platt Street, N.W.1., causing widespread devastation to the surrounding property including a very large block of flats and the "Star" P.H. at the corner of Platt Street and Goldington Street.War Reserve Smith, who was off duty but lived in the vicinity had returned from assisting at another incident at St. Pancras Hospital when he saw a parachute mine descending in the vicinity of Somers Town Police Station. He immediately went towards Pancras Square and while on his way the mine exploded. On arriving at the scene he rendered assistance, in the course of which he rescued a pregnant woman, and then heard cries for help coming from the first floor of the public house.This building appeared to be in imminent danger of collapse and part of it had to be pulled down next day, but War Reserve obtained a ladder (which was too short) climbed to the top of it and then hauled himself on to a balcony which went round the first floor. He climbed through a window and entered a room where he found a woman buried up to the neck in rubble and debris. He began to extricate the woman with his hands although pieces of ceilings and brickwork were falling and further bombs were still coming down in the neighbourhood.The woman was eventually released and carried to the window. War Reserve Smith then shouted to another police officer to fetch a longer ladder and when this arrived he put the woman over his shoulder and descended to the ground. She had by this time fainted.With the assistance of the woman's brother-in-law he took her to a Rest Centre and then returned to the scene of the incident and rendered what further assistance he could until 5.15 a.m. when he returned home, cleaned himself and reported for duty at 5.45 a.m. at Somers Town Police Station.Although War Reserve Smith was due to parade for duty at 5.45 a.m. the same morning he voluntarily rendered assistance at various incidents during the night. He attended a major incident at St. Pancras Hospital and then generally assisted at Pancras Square, in the course of which he rescued the two women. It is likely that had it not been for the efforts of this War Reserve the second women would have been buried by debris.The conduct of War Reserve Smith, who was off duty, was meritorious and his conduct was of a very high order.The acting Superintendent of the Division recommends War Reserve Smith for an award or mention in the London Gazette. The Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the District considers his conduct worthy of high award and recommends the award of the George Medal.'Whilst impressive this recommendation does little to underline the danger of the situation and can be better outlined by the testimony of the witnesses, firstly the victim of the bomb, Mrs. Constance E Keevil, who states:'My house partially collapsed, and as I attempted to leave my office the door collapsed on me, pinning me in the corner with the door, by this time the ceiling and walls were collapsing on me, burying me in the debris up to my shoulders. I was completely helpless, and shouted for help; this was answered by a man's voice, telling me to wait; shortly afterwards a policeman entered my office through the balcony window, he started to clear the debris off me with his hands, repeatedly telling me to keep calm. All the time he was doing this masonry was falling in patches and was dangerous to us both. He eventually cleared me of the debris, took me to the window and shouted for someone to bring a longer ladder, still doing his best to keep me calm, which I might say was a great effort on his part. The raid was still very heavy; the next I remember was being thrown over the P.C.'s shoulder and carried down the ladder when I completely collapsed.'P.C. Richardson adds his verdict:'The air raid was still in progress and of a severe character; the public house was in a very bad condition and liable to collapse further.In my opinion The War Reserve acted with great promptitude and courage, and at great personal danger considering all the circumstances of the night.'Sold together with copied research.…

The 2-clasp Naval General Service Medal awarded to Admiral Alexander Montgomerie, Royal Navy, who served at sea for almost twenty years and participated in a number of fiercly-fought actions, not least at Barque island; the subsequent capture of Guadeloupe; and at Rugen island where he successfully defended a fort against French infantry assaultsNaval General Service 1793-1840, 2 clasps, Anse La Barque 18 Decr 1809, Guadaloupe (Alexr. Montgomerie, Lieut. R.N.), good very fineProvenance:Sotheby's, March 1995.Colin Message Collection, August 1999.Jason Pilalas Collection, July 2024.Alexander Montgomerie, of an old Scottish family, was born at Dreghorn, Ayrshire, Scotland on 30 July 1790. Joining the Royal Navy at the tender age of 12 on 27 June 1802, he was initially appointed a First-Class Volunteer aboard the 16-gun sloop H.M.S. Hazard, with which he saw brief service in the English Channel before spending the next six years with both the 44-gun frigate H.M.S. Argo and the 74-gun H.M.S. Tigre, as a member of their Midshipman's berth. With Argo (under the command of Captain Benjamin Hallowell) young Montgomerie saw his first taste of action, as this vessel participated in the captures of St. Lucia and Tobago - the former earned Hallowell and his men a very favourable 'Mention', with Admiral Hood stating: 'To Captain Hallowell's Merit it is impossible for me to give additional Encomium, as it is so generally known; but I must beg Leave to say, on this expedition, his Activity could not be exceeded; and by his friendly Advice I have obtained the most effectual Aid to this Service, for which he has been a Volunteer, and, after the final Disembarkation, proceeded on with the Seamen to co-operate with the Army.' (London Gazette, 26 July 1803, refers).When Hallowell was appointed to command the Tigre, Montgomerie followed him and this ship was part of Admiral Lord Nelson's fleet in the great hunt for the combined Franco-Spanish fleet prior to the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. Tigre, unfortunately, missed the battle due to being away at Gibraltar to take on water and escort convoys, but subsequently participated in the operations off Egypt in 1807: Montgomerie must have been aboard when Tigre captured two Ottoman frigates (the Uri Bahar and Uri Nasard) and his subsequent biography states he was then employed with 'much boat service' on Lake Mareotis - scene of British landings against French, Ottoman, and Albanian troops.In September 1809, Midshipman Montgomerie passed his Lieutenant's examination and was thence sent (though still as Midshipman) to the 36-gun frigate H.M.S. Orpheus, before shortly afterwards removing to the 74-gun H.M.S. Sceptre - the ship with which he was to earn the clasps to his Medal. Sceptre, commanded by Captain Samuel James Ballard, was part of a force ordered to capture the French-held island of Guadeloupe. On 18 December 1809, a British squadron (including Sceptre) attacked two French ships (the Loire and Seine, variously described as 'frigates' or 'flutes') anchored at Anse a la Barque and protected by batteries of artillery ashore. Notwithstanding a spirited defence, in fairly short order both French vessels had been dismasted and surrendered - though they were subsequently abandoned, caught fire, and blew up. The attack was under the overall command of Captain Hugh Cameron of H.M.S. Hazard, and after destroying the Loire and Seine the British force next landed ashore to silence the batteries: this objective was also achieved but in the moment of victory Cameron was killed, one report stating that after personally hauling down the French tricolour he wrapped it around his body before being accidentally shot by a British sailor who mistook him for the enemy. It seems likely that Montgomerie played a very active part in this action, as the very next day he was appointed Acting Lieutenant of H.M.S. Freija/Freya, which was confirmed by official commission on 4 May 1810, and during the intervening time also appears to have been equally active in the ships' boats in minor actions against further French shore batteries around Guadeloupe.Returning home, after three months in command of H.M.S. Magnanime on 28 January 1811 he was appointed Lieutenant aboard the 32-gun frigate H.M.S. Aquilon, with which vessel he served until 1814, concluding his time aboard her as First Lieutenant. This period of his career also saw much active service - but rather than the tropical Caribbean, this time in the distinctly cooler North Sea and Baltic in the supression of enemy trade and coastal traffic, and the escorting of British and allied convoys. Though little further information appears immediately available, his service biography states that: 'When in the Baltic in 1812, and engaged with the boats under his orders in an attempt to bring some vessels off from the island of Rugen, he greatly distinguished himself by his conduct in capturing a temporary fort occupied by a superior number of troops, whom, on their being reinforced and endeavouring to recover their loss, he several times repulsed.' (A Naval Biographical Dictionary - Montgomerie, Alexander, W.R. O'Byrne, p.774, refers).Promoted Commander on 7 June 1814 on his return from the South America station, despite theoretical appointment to H.M.S. Racoon she was off the coast of Brazil and he never joined her. With the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars Montgomerie had to wait until 21 March 1818 for his next command - the 18-gun brig-sloop H.M.S. Confiance, which position he held for two years until moving in July 1820 to the 26-gun H.M.S. Sapphire as Acting-Captain. This was a fortuitous change as, two years later, Confiance was wrecked off Ireland with the loss of the entire crew. Returning home in September 1821, he does not appear to have received another seagoing appointment but nevertheless remained on the Active List until his official (and well-earned) retirement on 1 October 1856.By virtue of longevity, Montgomerie moved slowly up the seniority list; promoted Rear-Admiral in 1852, then Vice-Admiral in 1857, he reached the rank of Admiral on 27 April 1863. Admiral Alexander Montgomerie appears to have remained a bachelor throughout his life and died in January 1864 at Skelmorlie, Ayrshire, not far from where he was born 73 years earlier.Sold together with a small quantity of copied research.…

An extremely rare Edward VII gallantry K.P.M. awarded to Senior Constable J. C. Gates, New South Wales Police Force, the first Australian police officer to be so honoured and one of just four to receive the Edwardian issueIn his gallant pursuit of an armed burglar in North Sydney in April 1909, he exchanged fire until the latter ran out of ammunition, following which he closed with him to make an arrest: in the ensuing struggle, Gates was severely beaten about the head with the burglar's empty revolver, his wounds requiring 23 stitchesKing's Police Medal, E.VII.R., on gallantry riband (J. C. Gates, Sen. Const., N.S. Wales P.), minor edge bruises, good very fineK.P.M. London Gazette 14 January 1910.James Charles Gates was born in Christchurch, New Zealand on 28 February 1885, the son of a distiller. Opting for a new life in Australia when a teenager, he was working as a blacksmith when he enlisted in the New South Wales Police as a Constable.By the time of his K.P.M.-winning exploits in North Sydney, Gates had been advanced to Constable 1st Class but, as reported in various newspapers, he was about to receive accelerated promotion to Senior Constable.The incident in question commenced in Carabella Street, on the heights overlooking Neutral Bay, when an armed burglar broke into the house of Mr. Russell Sinclair in the early morning hours of 1 April 1909. Alerted by a lodger to the burglar's presence, Sinclair gave chase and a violent struggle ensued, in which he was twice shot in the groin. The burglar then made off down the street. Here, then, the moment at which Gates arrived on the scene. A newspaper report takes up the story:'It was after his escape into the streets that the fugitive waged another fight, this time with the constable who arrested him. When Constables McDonald and J. C. Gates, having been informed of that had occurred, proceeded to the locality, Gates saw a man near Milson's Point ferry. He watched the man, and at last he accosted him near Jeffrey Street. The man, who kept his right hand in his pocket, replied that he was on his way to visit someone in Carabella Street. The constable asked him why he kept his hand in his pocket, whereupon the man drew a revolver, fired, and then bolted. The shot missed Gates, who started off after the man, who, while he ran, turned and fired again twice, but still without effect. Constable Gates then fired, and an exchange of shots was kept up. The policeman was not hit but it was afterwards shown that one of his bullets grazed the fugitive's neck, causing a slight flesh wound. Gates, still in pursuit, reached his quarry near Livingstone Lane, and a hand-to-hand fight ensued.The man hit Gates a blow with the butt end of his revolver, and partially stunned him, but the Constable never allowed his prisoner to elude him, and was all the time endeavouring to hand cuff him. The Constable was furiously attacked, blow after blow being delivered about his head with the butt end of the revolver, and at length the man actually got free, but Gates, gallantly refusing to be beaten off, followed him and was joined by a civilian who had been alarmed by the noise of the conflict. Finding the chase hot, the fugitive dashed down some steps into an area in Fitzroy Street, and here he was finally captured, the Constable getting the hand cuffs on him.'The gallant Gates was duly awarded the K.P.M. as well as being advanced to Senior Constable. He was also presented with a Testimonial by the Mayor of North Sydney. His assailant - James Frederick Crook - was sentenced to death, a sentence later commuted to life.Gates died at Ghatswood in the northern district of Sydney in July 1955; sold with copied service record and newspaper reports.…

Sold by Order of a Direct DescendantThe outstanding Czech War Cross & Czech Bravery Medal group of ten awarded to Flight Lieutenant A. Vrana, Royal Air Force, late Czech Air Force and French Foreign Legion l'Armee de l'Air Groupe de Chasse 1/5Vrana had the admirable record of one kill and two probables during the Battle of France, having then transferred to Britain, he flew in the Hurricanes of No. 312 (Czechoslovak) Squadron during the Battle of Britain as just one of just 88 Czech Pilots1939-45 Star, clasp, Battle of Britain; Air Crew Europe Star; War Medal 1939-45; General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Cyprus (Flt. Lt. A. Vrana. R.A.F.); France, Republic, Legion of Honour, silver and enamel; Croix de Guerre, reverse dated '1939', with Palme upon riband; Czechoslovakia, Republic, Czechoslovak War Cross 1939, with three further Award Bars; Bravery Medal, with Second Award Bar; Military Merit Medal, silver; Army Commemorative Medal, 1st Type, mounted court-style as worn by Spink & Son, St James's, London, good very fine (10)Adolf Vrana - or Ada to his friends and comrades - was born at Nová Paka, Bohemia in October 1907. Having come of age, Vrana undertook his national military service and joined the Czechoslovak Air Force. First in the ground crew at Prague-Kbely and Hradec Králove fields, he was then selected for Pilot training. Vrana passed though in 1931 and was assigned to the 41st Fighter Squadron as a fighter pilot.He further gained skill in night flying, observation and also qualified on seaplanes, going to the Hranice Military Academy in 1934. Made Pilot Officer in 1936, he was with the 91st Squadron, at that time the only night fighter Squadron. Vrana thence trained as an instructor and a test pilot.Following the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, all its personnel found themselves without employment. Thus Varan and many of his colleagues made a break for it, arriving to the Consulate in Krakow some months later. The plan would be to make for Franch, which was completed via a coastal cruiser that took him to Calais.The French Foreign Legion was the option open, with the understanding that should a Second World War be declared, those in the service would then join Regular French Units. Some who had joined were fortunate to be transferred onto the most usual postings in Africa which were commonplace with the Foreign Legion, Vrana was still in France when War was declared. He was duly released to the l'Armée d'Air and went out to Chartres air field.Battle of France - first bloodHaving undergone familiarisation with the French systems and aircraft, Vrana operated the Curtiss Hawk 75 from Suippes, near Rheims with the Groupe de Chasse 1/5.The Battle of France saw Allied airmen gain significant experience in aerial combat, which would come to the fore in a few short months. Vrana wasn't to know that at the time, for they were regularly 'scrambled' to action on multiple occasions. Of his own record, Vrana was shot down on 13 May 1940 by a Me109, his life being saved by parachute after having bailed out. He shared in the destruction of a He111 on 26 May 1940 and shared in the probable destruction of a Hs126 and a He111 on 7 June 1940. As the German advance came on apace, the Group found itself moving to safety on numerous occasions.After the French collapse, Vrana and other Czechs flew their Hawks from Clermont-Ferrand to Algiers on 17 June. They made their way to Oran, at that point learning that France had fallen. Whilst at that place, together with four other gallant airman, Vrana was presented with his two French awards for his gallantry during the previous period of action. They then went to Casablanca, from where they went by boat to Gibraltar, where they joined a convoy bound for Britain, answering the call of Churchill that they would be welcomed to Britain to continue the fight.Battle of BritainProcessed into the Royal Air Force, he joined No. 312 (Czechoslovak) Squadron at its formation at Duxford on 29 August 1940. They were to be equipped with Hurricane Mark I's. They moved to Speke in September as part of the defence of Liverpool and her precious docks.Of his Ops with No. 312 Squadron, the Operational Record Books provide the following, all 'Scrambles':21 October - P3810 1135hrs.22 October - P3810 1620hrs.24 October - V6810 1310hrs.22 November - V6926 1040hrs.26 November - V6926 1155hrs.27 November - V6926 1625hrs.28 November - P3612 1250hrs.5 December - P3759 1120hrs.Further flightsBesides this, Vrana then assisted in transferring four of their aircraft on 8 December and would have been back in time for the visit of the Czech President on 17 December, who toured the Squadron and met the Pilots. At the end of his operational tour in April 1941, Vrana was posted to 3 ADF at Hawarden. Variously serving with No. 310 Squadron at Martlesham Heath in the Operations Room as a Flight Control Officer, he returned to No. 312 Squadron for a further Operational Tour in June 1942. Tour expired the following year, Vrana then went to serve at the Czechoslovak Inspectorate General and as Czechoslovak Liaison Officer at HQ Fighter Command, Bentley Priory.Returned to his homeland at the end of the conflict, he learned that his parents were lucky indeed to have survived time in a Concentration Camp. He rejoined the Czech Air Force when it was being rebuild and became Commanding Officer of the Research Institute and Testing Unit. His Czechoslovak War Cross 1939 with Three Bars followed in September 1945, being promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and Commander at Prague-Kbely field. When the communists took over in February 1948, he saw the way in which those who had served the Allied forces treated. It was clearly not a risk he wanted to take and Vrana escaped with his wife. Having been granted leave from the Air Force, he made it across to West Germany in late 1949. Vrana once again returned to the United Kingdom and rejoined the Royal Air Force. Having seen further campaign service in Cyprus (Medal & clasp), he retired Flight Lieutenant in May 1961. Granted the rank of Colonel in the Czechoslovak Air Force, he died in Wiltshire on 25 February 1997.His name is recorded on the National Battle of Britain Memorial and the London Battle of Britain Memorial, besides a memorial plaque in his home town and upon the Winged Lion Monument at Klárov, Prague.Sold together with an impressive archive of original material comprising:i) His riband bar, removed from his uniform, with gilt rosette upon 1939-45 Star denoting 'Battle of Britain'.ii) His R.A.F. Pilot's 'Wings'.iii) Czech Air Force Epaulettes.iv) Czech Pilot's dagger, marked 'Wlaszlovits, Stos', brass hilt with inlay, brass and leather scabbard, the blade of steel.v) Croix de Guerre aiguillette.vi) Data plate removed from an aircraft, marked 'Curtiss H75A-1 No. 43 1-39'.vii) Czech Pilot's Badge, by V. Pistoira, Paris, 1940, a rare award of French manufacture, numbered to the reverse 'F121'.With thanks to Simon Muggleton for accessing the ORB's.Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.SALE 25001 NOTICE:'Now offered together with his French Pilot's Badge, this officially numbered '33644', photographs available via SpinkLIVE.'

'H.M.S. Eclipse was escorting a Northern convoy on 29th March 1942 when in Arctic weather she fought an action with German destroyers of the Narvik class. In a running fight in the snow she badly damaged one of the enemy, hitting her six times with 4.7 shells. As the Eclipse was about to finish off this ship with a torpedo attack two other German destroyers appeared, and the Eclipse was hit. She hit one of the enemy, which did not pursue them, and she proceeded to Murmansk. She had been handled throughout with great skill and determination in very severe conditions, with one of her guns out of action owing to ice.'(The remarkably exciting award recommendation for Eclipse's crew following her life and death struggle in Artic Waters)An exciting Post-War C.V.O. group of nine awarded to Commander D. L. Cobb, Royal Navy, who was 'mentioned' as gunnery officer of Eclipse during a remarkable destroyer action in March 1942 which saw her cripple a German destroyer only to be engaged by two more enemy vessels and drive them offLater 'mentioned' again for good service in the Aegean including his bravery in the tragic sinking of Eclipse, Cobb went on to command Cockade when she brought relief to those affected by the 1957 Sri Lankan Floods and was heavily involved in implementing the Duke of Edinburgh's Award while a Deputy LieutenantThe Royal Victorian Order, Commander's (C.V.O.) neck Badge, silver and enamel, in its Collingwood box of issue; 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Africa Star; Italy Star; War Medal 1939-45, with M.I.D. oak leaf; Korea 1950-53 (Lt Cdr. D. L. Cobb R.N.), officially re-impressed; U.N. Korea 1950-54; Jubilee 1977, the last eight mounted court-style as worn, overall very fine (9)C.V.O. London Gazette 31 December 1977.David Laurence Cobb was born in March 1922 in Hendon, London, the son of Samuel and Mary Cobb. He joined the Royal Navy as a Naval Cadet on 1 May 1939 and was advanced Sub-Lieutenant during the Second World War. Posted to H.M.S. Eclipse he was 'mentioned' for his services during a convoy escort mission with her (London Gazette 23 June 1942). The award recommendation includes greater detail stating:'As Gunnery Control Officer, controlled a steady and accurate fire on the enemy, hitting him repeatedly, under very difficult conditions.'Still with her when she was transferred to the Aegean, Cobb received further plaudits for his cool and effective gunnery. This gunnery was put to the test during the Gaetano Donizetti action on 22 September 1943. This Italian freighter had been seized by the Germans to carry arms to Rhodes, escorted by the torpedo boat TA10. Eclipse encountered the convoy and attacked immediately, her guns were worked immaculately, sinking Gaetano Donizetti in minutes and damaging TA10 so heavily that she was scuttled days later.Cobb was again 'mentioned' for 'Operations in Dodecanese Islands culminating in the sinking of Eclipse on 24 October 1943' (London Gazette 4 April 1944 refers). The recommendation adds:'A painstaking and efficient G.C.O., always cheerfull [SIC] in adversity and setting a high example. His handling of the gun armaments was responsible for the successful outcome of two engagements in the Dodecanese against surface craft.'Still with her the next month Cobb was present for the horrific sinking of Eclipse, when she struck a mine on 24 October and broke in two, sinking within five minutes. Of the ships complement of 145 men there were only 36 survivors and tragically at the time she was also carrying 'A' Company, 4th Battalion, Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment), who lost 134 men out of 170.Cobb was extremely lucky to survive the sinking and joined the complement of Beaufort on 18 December 1943. This vessel was stationed in the Aegean as well and was present for the bombardment of Kos and later the failed attempt to halt the German invasion of Leros.Post war Cobb continued to serve being promoted to Lieutenant Commander on 16 February 1950 and later Commander in 1953. Posted to command H.M.S. Cockade in 1957, taking part in relief efforts of the Sri-Lankan Floods of 1958. That same year Cobb took part in the Navy Pageant at the Royal Tournament.Placed upon the retired list on 2 January 1961 and was appointed assistant secretary of the Duke of Edinburgh Award scheme. Appointed Deputy Director of the Duke of Edinburgh Award scheme in 1977 and the same year Deputy Lieutenant of Greater London. It was likely for his work with the Duke of Edinburgh Awards that he was awarded his C.V.O.. Cobb died at Sydney, Australia on 29 January 1999; sold together with copied research.…

The scarce Sergeant-Pilot's group of eight awarded to Sergeant F. E. Nash, Royal Air Force, later Major, Royal Artillery, who shot down German Ace Paul Felsmann in 1918 and then became a Prisoner of War in the same action, coming away with a number of interesting photographs of his captivity and later wrote a diary of his experiences during the Second World WarBritish War and Victory Medals (10206. Sgt. F. E. Nash. R.A.F.); 1939-45 Star; France and Germany Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Territorial Decoration, dated to the reverse '1945' with second award bar dated '1949'; France, Republic, Croix de Guerre, with Palme, mounted court-style for wear, overall good very fine (8)Croix de Guerre confirmed in an amendment of The Chronicles of 55 Squadron R.F.C. - R.A.F.Frank Elliot Nash was born at Kington, Herefordshire on 26 November 1897 and settled in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire later in life. Enlisting with the Royal Flying Corps on 19 October 1915 as an Armourer he underwent Pilot Training with No. 8 Squadron being awarded his Wings on 2 April 1918. Re-mustering as a Sergeant Mechanic on 2 April 1918 he joined No 55 Squadron as a pilot flying D.H.4.s on 8 July 1918.Crash LandingWith this unit he launched a bombing mission over the Oberndorf Mauser Munitions Works on 20 July 1918 with Sergeant W. E. Baker as his observer. The Squadron was attacked by Albatros fighters with one D.H.4.- piloted by Lieutenant R. A. Butler being shot down- Baker shot down the Albatros immediately after its victory. This was likely Offizierstellvertreter Paul Felsmann, of K4b who was listed as killed in action at the same area that day.Even as they Baker emptied his weapon into Felsmann's aircraft, a second Albatros attacked, stitching the aircraft with rounds, hitting the fuselage and killing Baker. Nash's radiator was holed and hot water and steam splashed over his legs however despite this he was unharmed and managed to keep flying. The Albatros continued to press the attack with Nash remaining in formation as long as possible but, with his Observer dead, he was open and couldn't defend himself.Bullets tore through his shoulder and parts of the fuel tank lodged in his back, these wounds also knocked him unconscious and the D.H.4. dropped into a dive. Nash regained consciousness at 7,000 feet and managed to pull himself out of the plunge despite his wounded arm. This was made more difficult by the body of Baker which had fallen against his emergency stick.He levelled out only a few feet above the ground but was certainly still going down, Nash picked out a small field and attempted to lose some height. Unfortunately he hit a small ridge which tore the undercarriage out from his aircraft and he was deposited from 15 feet onto the ground. Emerging uninjured it is a mark of Nash's character that his first act was to try and remove Baker's body as he didn't want to burn it with the aircraft.His victor- either Vizefeldwebel Happer or Offizierstellvertreter Pohlmann- landed next to him and took him prisoner, offering him a 'particularly nasty cigarette' in consolation. As is often the case with bomber pilots, he needed to be protected from the citizens of the town he was bombing and it was in front of an angry mob that Nash was taken to Oberndorf Hospital, being put in the basement for his own safety. This proved to be a stroke of good luck however as he was sheltered from the second raid his squadron launched the next day when 200 tons of bombs were dropped.Prisoner of WarWhilst at the hospital he was able to attend the funeral of his observer Sergeant Baker and Lieutenant Young- whose aircraft was shot down before his- at Oberndorf cemetery. Butler, Young's observer, was not found for several weeks, having jumped from the aircraft to escape the flames. Nash was photographed at the funeral, wearing his uniform with a borrowed German cap.Taken to Tubingen Hospital he was treated there for the next two months, slowly recovering from the bullet and shrapnel wounds he had taken to his back and shoulder. Repatriated on 20 December 1918 he was further discharged on 26 March 1919.Return to the Colours - FranceNash was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant on 26 May 1937 with 42nd (Foresters) Anti-Aircraft Battalion. Further advanced Lieutenant after the outbreak of war on 1 August 1940, photographs sold with the lot make it clear that he was managing searchlights during this period.Promoted Captain in 1944 he joined the British Army on the continent on 22 June, his diary of events during the war describes his first sight of France stating:'Cannot accurately described the sight of Utah Beach. Literally thousands of craft of all shapes and sizes. Big battle in progress towards Caen, columns of black and purple smoke and very heavy artillery duel going on.'He goes on to describe his role in France which appears to have been rather unusual and certainly included some intelligence work:'Busy time on job. Jack-of-all-trades Interpreter, water engineer, undertaker, questioners of "Collaborators", etc. Giver out of permits to travel. Everything tranquil except for Boche night bombers thousands of prisoners going back all day to cages. Did an interrogation for Yanks, (65 P.O.W.s) could only find two who spoke German, others were Russians in German Uniforms!!'He was present for the Liberation of Paris and marvelled at the calm of the crowds, pouring into the streets and waving allied flags even as the Battle continued in the city. He gives a hair-raising account of one sticky moment when the fighting caught up with him quite alarmingly:'Moved baggage into billet about 14-00. 16-00 hours a terrible fusillade started all over the city. (De Gaulle came from Ave du [….] to Notre Dame.) Jerries and Milice arrived firing down from rooftops. About 17-30 our hotel attacked from courtyard at rear and adjoining roofs. Hardly a window left after 5 mins. Mons le Patron, wife and family very frightened. Returned fire with all available weapons Sgt Walsh (.45 Tommy) knocked one Boche from roof top into courtyard! Situation saved by arrival of platoon of F.F.I.'GermanyAdvancing swiftly through France and Belgium via Arras and Lille he was soon into Germany. Here the diary depicts yet more tension as Nash describes the reaction of the frightened and hostile population to their presence and sleeping with a loaded revolver under his pillow.He was reassigned to the Military Government Department in Diest, Belgium, being assigned to the village of Binkom. Posted to 229 (P) Military Government Department as a Staff Officer Nash was sent into Germany to help ease the administrative problems surrounding the Allied Invasion, encountering if anything greater tension than ever before. On one occasion the town in which he was billeted was strafed by several M.E.109s, with the townspeople finding themselves not only occupied but under attack by their own Luftwaffe.Stationed in Hanover he was ordered to help maintain order in the city which had been heavily damaged in its capture. Nash's diary takes up the story:'Incredible sight in Rathaus Platry [Rathausplatz], thousands milling around all wanting something! Very large proportion being German civilians reporting that (a) they had no food on accommodation, (b) their houses or what was left of them, had been plundered by DP's (c) someone had been murdered.'A volunteer police force had been recruited from the local population to try and keep order however Nash relates that '90%' of them had been killed by the time of his arrival. He cornered the leading civilian official in the town, a Dr Knibbe and 'Ordered him implicitly (Knibbe) to …