Created of various shells including Abelonem with geode and feathers, height 7 inches (17.8 cm), width 11 3/4 inches (29.9 cm); Together with three metalic leaf form brooches.Please note this lot is offered AS IS.Please note this lot is offered AS IS.Any condition statement is given as a courtesy to a client, is an opinion and should not be treated as a statement of fact and our Organization shall have no responsibility for any error or omission. Please contact the specialist department to request further information or additional images that may be available.Request a condition report

We found 27399 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 27399 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

21st centuryOf triangular form, arranged with rows of white shells with white feather borders.Length 24 inches (60.9 cm).No condition report? Click below to request one. *Any condition statement is given as a courtesy to a client, is an opinion and should not be treated as a statement of fact and Doyle New York shall have no responsibility for any error or omission. Please contact the specialist department to request further information or additional images that may be available.Request a condition report

The first in black and white beadwork with birds, the second in green, red, blue, yellow and white, the last in red and black. Heights of hats 17, 18 and 20 inches. with two metal stands. Together with a Yoruba beadwork lizard-form sash decorated with masks and a dog in red on a white ground within blue borders, the feet stitched with cowrie shells. Length 40 inches, width 9 inches.No condition report? Click below to request one. *Any condition statement is given as a courtesy to a client, is an opinion and should not be treated as a statement of fact and Doyle New York shall have no responsibility for any error or omission. Please contact the specialist department to request further information or additional images that may be available.Request a condition report

Northern France, Champagne, Troyes, circa 1520 A.D. Rectangular window panel set in modern lead cames with loop to each upper corner; design of sea-beasts in profile with their curved tails bound with thick collars, conch shells between. 500 grams, 39.3 x 12.5 cm (15 1/2 x 4 7/8 in.). [No Reserve] with De Baecque Vente Aux Encheres, 5 March 2022, no.40.

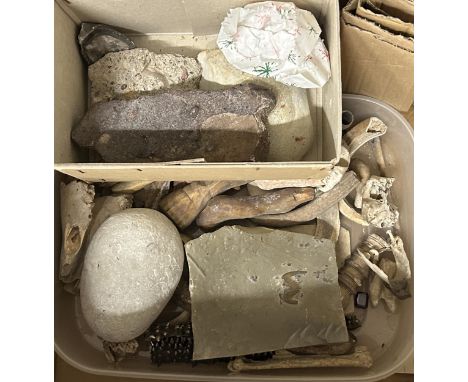

Cretaceous Period, 145-65 million years B.P. A pair of Charonosaurus sp. hadrosaur eggs on a matrix retaining evidence of the original leathery surface. 7.6 kg total, 26 x 14 cm (10 1/4 x 5 1/2 in.). From a Lincolnshire, UK, collection, 1990s. Property of a Cambridgeshire gentleman.Dinosaur eggs are known from about 200 sites around the world, the majority in Asia and mostly in terrestrial (non-marine) rocks of the Cretaceous Period. It may be that thick calcite eggshells evolved during the Cretaceous (145 to 65 million years ago). Most dinosaur eggs have one of two forms of eggshell that are distinct from the shells of related modern animal groups, such as turtles or birds; however, some eggs closely resemble the type of shells seen in present day ostrich eggs.

2nd-3rd century A.D. Comprising a plain hoop with hook-and-eye fastener, discoid shield decorated with filigree border of three bands of twisted wire and seven granules; to the centre, a bezel of spirally twisted wire; a broad hoop from previous pendant attachment. Cf. Ruseva-Slokoska, L., Roman Jewellery: A Collection of the National Archaeological Museum, Sofia, 1991, item 32, for type. 3.31 grams, 18.24 mm (3/4 in.). [No Reserve] Acquired on the UK art market in the early 2000s. From the David John Dennis collection of ancient jewellery. Property of a Californian, USA, collector.David Dennis started collecting items when he was a 10 year old boy during the Blitz in London gathering parts of nose cones from shells and other pieces of shrapnel that had fallen from the skies. After the war he turned his attentions to cigarette cards, postage stamps, bank notes, coins and eventually ancient artefacts, predominately Roman jewellery. Now living in Cumbria with his daughter he decided it was time to part with his collections.

2nd-4th century A.D. With 'swan-neck' junction; facetted, round-section tapering shank; shallow bowl shaped like a flask in profile. Cf. Riha, E., & Stern, W.B., Die Römischen Löffel aus Augst und Kaiseraugst, Forschungen, in Augst 5, 1982, for discussion; cf. Jackson, C.J., The Spoon and its History, in Archaeologia, vol.53. 19.7 grams, 17.5 cm (6 7/8 in.). Property of a Bedfordshire, UK, private collector. Accompanied by an illustrated collector's identification tag.The spoon's shaft tapers to a point; it was used for extracting seafood or snails from their shells. Spoons executed in precious metals were highly valued items in this period in history, so much so that historians and classicists see them recorded in inventories compiled for noble households. Cochlearia like this one have even been discovered in treasure hoards. The absence of Christian symbolism or of a Christian inscription on this spoon might suggest that it dates from a pre-Christian era, or that its owner/commissioner was pagan.

A shell cameo bracelet, Italy, set with five oval shells carved with muses, mounted in 14ct gold, length 17cm, British import hallmarks, date letter for 1976, gross weight 33 grams Two of the cameos are cracked.PLEASE NOTE:- Prospective buyers are strongly advised to examine personally any goods in which they are interested BEFORE the auction takes place. Whilst every care is taken in the accuracy of condition reports, Gorringes provide no other guarantee to the buyer other than in relation to forgeries. Many items are of an age or nature which precludes their being in perfect condition and some descriptions in the catalogue or given by way of condition report make reference to damage and/or restoration. We provide this information for guidance only and will not be held responsible for oversights concerning defects or restoration, nor does a reference to a particular defect imply the absence of any others. Prospective purchasers must accept these reports as genuine efforts by Gorringes or must take other steps to verify condition of lots. If you are unable to open the image file attached to this report, please let us know as soon as possible and we will re-send your images on a separate e-mail.

A GROUP OF VARIOUS PORTMEIRION ITEMS to include a pair Gray's Pottery 'Portmeirion Ware' 'Tiger Lily' patterned rice (hairline crack to the lid) and sugar storage jars, height 17cm, a 'Gold Check' coffee pot, height 32cm (chip to the rim and handle, slight nibble to the lid, scratch to the pattern near the base), a 'Malachite' patterned dish with a gilt rim, diameter 10cm (slight wear to the gilt rim), a yellow 'Vinegar decanter' with a stylised dolphin pattern and gilded rim (no stopper, small chip to the rim), and an unmarked storage jar with printed sea shells and sea animals, height 12.5cm x diameter 11cm (hairline crack, signs of discolouration, chip to the underside of the rim), (6) (Condition Report: itemised conditions above, varying degrees of crazing across the items)

A CENTRAL AFRICAN KUBA MASK, CONGO, 20TH CENTURY of carved wood with apertures for the eyes, the outer surface partially covered with sheet copper at the front, a fringe of hair at the top, decorated over its surface with designs of white and turquoise beads enriched with small shells, the base with pairs of rattles, and additional flaps at the front and back decorated with further designs of shells and beads, 32.0 cm high

TWO VICTORIAN SILVER CHATELAINES, BOTH LONDON, 1873 one with shaped oval cartouche to clip pierced and engraved with shells and foliage around an engraved coat of arms and initials RJ, hung with four belcher chains ending in Albert clasps, S. Mordan & Co., 24.5cm long, the other with a shaped openwork cartouche to clip foliate engraved, hung with five short belcher chains ending in decorative swivel Albert clasps, Thomas Johnson, 13cm long; 156g

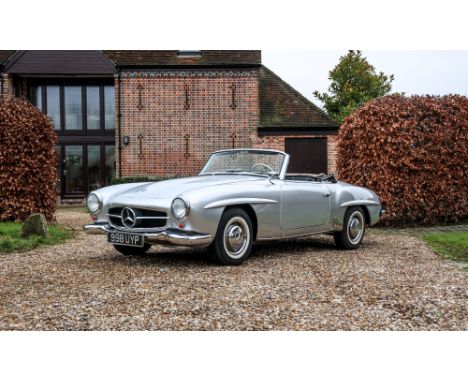

• Extensive restoration over a number of years • Complete with original hardtop and storage frame • Comprehensive history file including new MoT test certificate Originally spotted by the vendor during a drive through the German countryside, this 190 SL was in classic ‘barn-find’ condition and had been in this state for a number of years, the result of a deceased spouse. After an equitable arrangement was arrived at, it was then imported into the UK in 1973, as per the original H.M. Customs & Excise document shown in the history folder. Including, of course, a number of other official import documents, including notification of vehicle arrival (NOVA). The official date of manufacture was later confirmed by Mercedes-Benz as the 21st March 1960, a formal document received after an extensive period of restoration with initial UK registration taking place in April 2016. MoT test certificates are also filed for 2015 and 2017 with a brand new one for the year 2025/2026 as well as vehicle tax from 2017 onwards, despite the zero historic vehicle cost. Almost all parts that were damaged or corroded have been sourced by official German and English SL specialists, notably rebuilt Solex carburettor kits, all suspension components amongst many more from SLS in Hamburg and Motorvation, a complete new subframe from AFL in London, Niemöller in Mannheim and bumpers, carbs, brakes and steering as well as numerous other parts and labour from Hilton & Moss in Essex. Much of the later restoration took place by Motorvation, a classic car restoration specialist based in Hertfordshire and established back in the 1980s. Over the past 40 years, Motorvation has been involved in classic car servicing, restoration, classic race/rally preparation and caring from a basic oil change right up to fast-road suspension set-up for a Goodwood Group 5 Lancia Stratos. Much work was undertaken including a rebuilt dynamo, a hood frame that was prepared for the preparation and fitting of all material panels to include the removal and re-fitting of the front windscreen and wooden dashboard sections. Quite apart from the complete engine bench-strip and rebuild in 2012, significant restoration of the coachwork has also taken place with new front floors, exhaust sections and other parts to fit. Needless to say, all bright-work has been re-chromed and refitted with magnificent reflective surfaces all round. Steering was built back up as indeed were the electrics throughout. In fact, from the suspension to the heater matrix and pretty much everything in-between has been stripped down, re-built and re-installed costing many thousands of pounds. If fact, going through the heavy Leaver-Arch file of invoices, the costs are significantly more than the reserve set by the vendor. Indeed, the process as a whole took, reportedly, nigh on 15 years. The rebuild was thorough and included stripping the engine down, polishing the crankshaft, resurfacing the valves and seats, re-boring the block and grinding the thrust faces to suit the shells. The radiator has been re-cored by the right people, Feltham Radiators Ltd. There were numerous issues to overcome but all were addressed methodically and correctly until the engine was fully installed and ready to run. This was all taken care of by Motorvation and Bob Harman Performance Ltd of Hertfordshire. Motorvation rebuilt the Solex carburettors although, at time of writing, they are still problematic and so Silchester Garage in Hampshire, well respected SL specialists are going through the car in preparation for the sale which will include the carburettors, headlights, some trim and various other elements that need tidying up. The interior appears to be in excellent condition with good but original front leather seating and completely re-upholstered fresh carpet, trim and all associated additional detailing. New Vredestein Sprint Classic tyres are fitted to each corner with matching chrome and painted hubcaps as well as an original (but worn) spare in the boot, even the correct jack is present. All instruments and lighting have been re-wired correctly and linkages re-aligned right down to the glove compartment lid and associated chrome strip. It has clearly been well restored over the years with body panels correctly by Smooth Classic Restorations and mechanically overhauled by a series of professional and dedicated specialists right down to the soft and hardtop. This represents an extremely fine example, well documented and arguably in one of the most desirable and marketable colour schemes. Furthermore, it benefits from a matching hardtop, something that is not always present with these W121's and certainly not easy to find. Supplied in splendid condition with a comprehensive history alongside and certainly an example that could carry off any amount of winner’s silverware. Consigned by Edward Bridger-Stille Interested parties should note that, once this car has been sold, it will be collected by Mercedes-Benz specialist, Silchester Garage, and have the works finished on the hardtop/rear-screen and fitted prior to delivery. All this to take place at the vendor's expense. EXTENSIVE RESTORATION OVER A NUMBER OF YEARSCOMPLETE WITH ORIGINAL HARDTOP AND STORAGE FRAMECOMPREHENSIVE HISTORY FILE INCLUDING NEW MOT TEST CERTIFICATE

A Pair of 1960s Italian Lucite Nautical Table Lamps, with sea life inclusions, including crabs, star fish, shells and seaweed, unmarked,16.5cm high excluding fitments, with later shadesMatched Pair of 1960s Italian Lucite Nautical Table Lamps, with sea life inclusions, including crabs and shells, unmarked,22.5cm high excluding fitments, with later shades (4)1. Black ground lamp has minor surface wear, tiny nicks to base, glue visable on the join to the bulb holder. 2. Blue ground lamp has a nick to the front, some surface wear. 3. Clear ground lamp has a crack through the base, nick to front edge, dirty, some surface wear. 3. Clear ground lamp has an air bubble in the top shell, dirty and dusty, some surface wear.

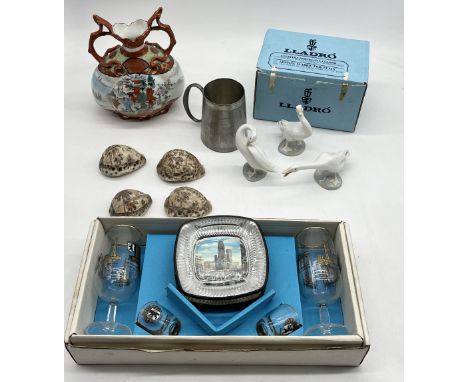

African hardwood figure, standing, H.45cm; 2 busts, H.19.5cm the tallest; model of a Hippopotamus, W.21cm; rhinoceros, elephant, 3 crocodiles, Japanese bronze vase, H.21.5cm; set of 6 bamboo coaster, each decorated with a moth, in a holder with handle; glove stretchers, brass leaf dish, door porter, and 2 shells. (22)

This lot includes two distinctive handcrafted bracelets. The first bracelet features multiple strands of vibrant orange seed beads with a natural wood clasp, creating an earthy, bohemian style. The second bracelet showcases a wide cuff design, intricately woven with small cowrie shells, interspersed with colorful yellow and orange beads, lending it a lively, coastal aesthetic.Issued: 21st centuryDimensions: 8.5"LCondition: Age related wear.

A Vitra Eames-style white lounge chair and ottoman, the shells crafted in light wood veneer and the covers in white leather with polished aluminium frames, no label, the chair measures approx 86w x 75 x 84 h cms. The ottoman measures 65 x 53 x 43 cms. Provenance: Property of a Kensington lady -

Set of Six Elbow or 'Tub' Chairs Attributed to Robin Day for Hille Designed and released 1967, these of the period, the shells with applied coloured leather or leatherette upholstery and raised on chromed tubular supports, no visible exterior marks.60.5cm wide, 53cm deep, 77cm highWear commensurate with age and use, the base of the burgundy chair slightly loose, would benefit from cosmetic attention but stable and ready to use, additional images available.

Coquilles, an R. Lalique opalescent and polished glass bowl, the exterior moulded in relief with four stylised shells, wheel etched mark to underside21cm diameterA couple of minor nicks to rim (barely visible), otherwise in good overall condition, very light scratching commensurate with age and use.

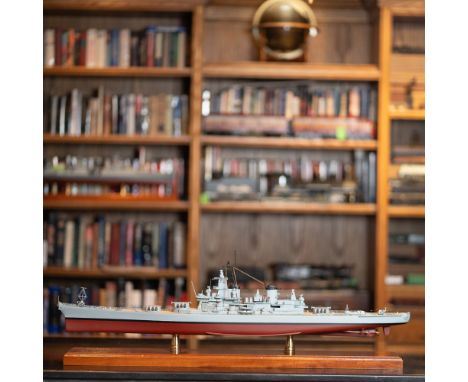

This is a finely crafted scale model of the USS Missouri (BB-63), the iconic Iowa-class battleship that played a pivotal role during Operation Desert Storm (1990-1991). This detailed replica captures the essence of one of the most storied naval vessels in U.S. history, known as the "Mighty Mo." The model showcases intricate craftsmanship, featuring a helicopter landing pad, powerful gun turrets, radar arrays, and deck detailing. Mounted on a polished wooden base with brass supports, this piece is a stunning homage to the naval might of the USS Missouri during its final combat deployment. The USS Missouri was part of Task Force 155, providing critical firepower in the Gulf War. During Desert Storm, it launched Tomahawk cruise missiles and delivered devastating naval gunfire support, cementing its legacy as one of the greatest battleships in U.S. naval history. Key details include: Highly detailed representation of the USS Missouri during its Desert Storm configuration. Features helicopters, deck weapons, and radar systems in precise detail. Painted in authentic naval greys with operational deck markings. Mounted on a polished wooden base for an elegant display. Historical Significance: The USS Missouri, commissioned in 1944, is best known for serving in World War II, the Korean War, and its final mission during Operation Desert Storm. It was on the Missouri's deck that Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender to end World War II. In Desert Storm, it proved the enduring value of battleships, launching 28 Tomahawk missiles and firing over 700 16-inch shells, supporting coalition forces during one of the largest military campaigns of the 20th century. This model is a tribute to the ship's legacy, celebrating its role in Desert Storm and its place in naval history. This item has a base included. Issued: 20th centuryDimensions: 41"L x 6"W x 13.25"HCondition: Age related wear.

An exceptional Kongo "Nkisi Nkondi" figure" Few African sculptures are as iconic as human figures covered in hardware. Such figures,variably called “nail fetish”, “power figure”, or “nkisi nkondi”, were long considered byEuropean observers as quintessential expressions of witchcraft and superstition. They are, in fact,sophisticated medical and legal remedies of the Kongo peoples, a cluster of ethnic groups thatlive at the mouth of the Congo River in Central Africa. The Kongo made such figures to housespiritual beings that could be activated in order to intervene in human affairs. They were adjuredto heal illnesses, settle disputes, take oaths, punish wrongdoers, and protect the community.In its original setting, this sculpture functioned as the vessel for a spirit. It is called nkisi, a termthat designates both the ancestor or nature spirit that inhabited it, and the container itself. Nkisican also be translated as “sacred remedy”. A nkisi-receptacle can take a variety of forms, like abasket, a shell, or a glass bottle. A container in the shape of a human figure with pieces of iron iscalled a nkisi nkondi, “a hunter spirit-vessel”. Such a power figure used to hunt thieves,bewitchers, and people who had broken taboos or who did not keep their word. Each nail, screw,and blade driven into the wood corresponds with a specific request for action addressed to thenkisi-spirit, whose supernatural powers were invoked and stirred up. The figure now constitutes anotarial record, so to speak, documenting in iron all the pleas, agreements, oaths, curses anddemands for vengeance that it was presented with and of which it took care.Works like this resulted from the collective vision of several people rather than a single artist,and changed dramatically in appearance over time. A sculptor carved an empty figure in wood,which a ritual expert subsequently loaded with sacred medicines. These magical substances werelocated in the square box on the belly and in the charge on top of the head, both sealed in placewith resin. Spirit-embedding medicines were necessary to attract and fix a nkisi in the vessel, andoften included earth from a grave site. Once “contained”, spirit-admonishing medicines wereused to entreat the spirit in a controlled manner so that it could act for the benefit of an individualor a community. Over the course of decades, priests, healers, and users added substances to thefigure, to trigger its powers, to seal agreements, or to remind the nkisi what to do and where togo. Today, the figure is covered with shreds of cloth tied to nails or bundled into small packages,and with pierced shells, fruits, seedpods and tops of gourds attached to metal rings or hangingfrom pieces of rope. The attachments also include different kinds of glass beads, as well as smallcarved wood pieces, one of which may show a stylized face. The additions are so dense that thefigure’s left arm, with the hand resting in the hip, is no longer visible.All the body poses and attachments of a nkisi nkondi have specific meanings. The raised rightarm, which once held a knife, is at once defensive and offensive. The four fingers of the right hand, forming a circle, with the long thumb pointing upwards, refer to the earth and heaven, thussymbolizing the unbreakable bond created by the spirit when activated. The combination of onehand upraised and the other in the hip is common among persons of authority. It signifies theability to review a situation and act accordingly. The figure’s open mouth indicates, among otherthings, the need to feed the spirit in order to encourage it to perform a particular action, as wellas its eloquence in administering justice. The mirror that covers the abdominal box and the glasseyes, made from imported materials, were meant to enhance the nkisi’s clairvoyance, necessaryto perceive the human and the spirit worlds. Many attributes of a power figure make sensebecause of sound associations and word puns in the Kongo language. For instance, one of theshells attached on the front, which appears also on other nkisi nkondi, has a spiral form. Such aform is called nzinga, a word that evokes luzinga, “long life”. The various seedpods attached tothe figure have not yet been identified and we do not know their indigenous names. Yet we canassume that these names, too, reveal some desired outcome.This nineteenth-century nkisi nkondi, with its exceptionally dense and well-preservedattachments, belonged to the Belgian botanist and folklorist Jean Chalon (1846-1921). Hementioned it in a publication from 1920. The power figure has not been altered since it leftAfrica. The countless additions testify to its long-lasting success as a protective guardian andpunitive hunter."Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers45 cmProvenanceBelgian botanist and folklorist Jean Chalon (1846-1921).LiteraturePublished in CHALON, Jean. 1920." Fétiches, idoles et amulettes". S. Servais: Jean Chalon. Volume 1, p. 12(no image)LiteratureLEHUARD, Raoul. 1980. Fétiches à clous du Bas-Zaïre. Arnouville: Arts d’Afrique noire.MACGAFFEY, Wyatt. 1993. “The Eyes of Understanding: Kongo Minkisi”, pp. 18-103 inAstonishment and Power, W. MacGaffey and M. Harris. Washington and London: SmithsonianInstitution Press.THOMPSON, Robert Farris. 2002. “La gestuelle kôngo”, pp. 23-129 in Le geste kôngo, ed. C.Falgayrettes-Leveau. Paris: Éditions Dapper.

Schwanen-Speiseservice. Meissen. 1984. Breite: 29,5-34,5 cm, ø 16-24,5 cm, Höhe: 14 cm. 8,5 Kg. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Sauciere mit hochgestelltem Delphin-Henkel. 18 Teile: 2 Speiseplatten, 1 Henkelschale, 1 Sauciere, 1 runde Schale, 1 Schüssel, 6 Essteller, 6 Dessertteller. Pressmarken, Malermarken, Schwertermarken, eine Speiseplatte 1924-1934, eine Schwertermarke mit Punkt. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 12.925,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:18 Uhr (CET)Swanen dining service. Meissen. 1984. Width: 29.5-34.5 cm, ø 16-24.5 cm, height: 14 cm. 8.5 kg. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, painted with Native American flowers, painted in color and gold. Sauce boat with raised dolphin handle. 18 pieces: 2 dinner plates, 1 bowl with handle, 1 sauce boat, 1 round bowl, 1 bowl, 6 dinner plates, 6 dessert plates. Press marks, painter's marks, sword marks, one dinner plate 1924-1934, one sword mark with dot. Meissen manufactory price: 12.925,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:18 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

6er Satz Schwanenservice-Suppentassen. Meissen. 1980er Jahre. Modell-Nr. 5081. Höhe: 9,5 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Halbkugeliger Korpus mit seitlichen Delphinhenkeln, Deckel mit plastischem Schneckenknauf. Malermarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 5994,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:18 Uhr (CET)Set of 6 swan service soup cups. Meissen. 1980s. Model no. 5081. Height: 9.5 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Hemispherical body with dolphin handles on the sides, lid with scroll-shaped finial. Painter's marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 5994,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:18 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

Schwanen-Mokkaservice. Meissen. 1974-1980, 1989. ø 11-16,5 cm, Höhe: 5-18,5 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Kannen und Tassen mit Delphinhenkel, Deckel mit plastischem Schneckenknauf. 21 Teile: Mokkakanne, Milchkännchen, Zuckerdose, 6 Mokkatassen, 6 Untertassen, 6 Dessertteller. Pressmarken, Malermarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 9496,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:19 Uhr (CET)Swan mocha service. Meissen. 1974-1980, 1989. ø 11-16.5 cm, height: 5-18.5 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Jugs and cups with dolphin handles, lids with sculpted scroll pommel. 21 pieces: Mocha pot, milk jug, sugar bowl, 6 mocha cups, 6 saucers, 6 dessert plates. Press marks, painter's marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 9496,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:19 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

Schwanen-Kaffeeservice. Meissen. 1986-1996. ø 15-20 cm, Höhe: 5-25 cm. 5,2 Kg. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Kannen und Tassen mit Delphinhenkel, Deckel mit plastischem Schneckenknauf. 21 Teile: Kaffeekanne, Milchkännchen, Zuckerdose, 6 Tassen, 6 Untertassen, 6 Dessertteller. Pressmarken, Malermarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 11.647,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:19 Uhr (CET)Schwanen coffee service. Meissen. 1986-1996. ø 15-20 cm, height: 5-25 cm. 5.2 kg. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Jugs and cups with dolphin handles, lids with sculpted scroll pommel. 21 pieces: Coffee pot, milk jug, sugar bowl, 6 cups, 6 saucers, 6 dessert plates. Press marks, painter's marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 11.647,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | presumably 13:19 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

Schwanen-Kaffeeservice. Meissen. 1986-1991. ø 14-20 cm, Höhe: 5-25 cm. 5,2 Kg. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Kannen und Tassen mit Delphinhenkel, Deckel mit plastischem Schneckenknauf. 21 Teile: Kaffeekanne, Milchkännchen, Zuckerdose, 6 Tassen, 6 Untertassen, 6 Dessertteller. Pressmarken, Malermarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 11.647,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:20 Uhr (CET)Schwanen coffee service. Meissen. 1986-1991. ø 14-20 cm, height: 5-25 cm. 5.2 kg. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Jugs and cups with dolphin handles, lids with sculpted scroll pommel. 21 pieces: Coffee pot, milk jug, sugar bowl, 6 cups, 6 saucers, 6 dessert plates. Press marks, painter's marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 11.647,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | presumably 13:20 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

6er Satz Schwanenservice-Gedecke. Meissen. 1995-1997. ø 14-20 cm, Höhe: 9 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Tassen mit Delphinhenkel. 18 Teile: 6 Tassen, 6 Untertassen, 6 Dessertteller. Pressmarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 7368,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:20 Uhr (CET)Set of 6 swan service place settings. Meissen. 1995-1997. ø 14-20 cm, height: 9 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Cups with dolphin handles. 18 pieces: 6 cups, 6 saucers, 6 dessert plates. Press marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 7368,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:20 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

Paar Schwanenservice-Gedecke. Meissen. 1986, 1997. ø 15-20 cm, Höhe: 5 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, korallenrot und gold staffiert. Tassen mit Asthenkel von 1963 (selten, nicht mehr im Sortiment). Malermarken, Pressmarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 2156,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:23 Uhr (CET)Pair of swan service covers. Meissen. 1986, 1997. ø 15-20 cm, height: 5 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colorful painting with Indian flowers, coral red and gold painted. Cups with branch handles from 1963 (rare, no longer in the assortment). Painter's marks, press marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 2156,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:23 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

Schwanenservice-Teekanne. Meissen. 1995. Modell-Nr. 5726. Höhe: 15 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Kanne mit Delphinhenkel, Deckel mit plastischem Schneckenknauf. Malermarke, Pressmarke, Schwertermarke. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 1790,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:23 Uhr (CET)Swan service teapot. Meissen. 1995. model no. 5726. Height: 15 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Jug with dolphin handle, lid with sculpted scroll finial. Painter's mark, impressed mark, sword mark. Meissen manufactory price: 1790,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:23 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

3er Satz Schwanenservice-Platzteller. Meissen. 1988, 1995. Modell-Nr. 5478. ø 31,5 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, gold staffiert. Malermarken, Pressmarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 2847,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:24 Uhr (CET) Set of 3 swan service plates. Meissen. 1988, 1995. model no. 5478. ø 31,5 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, painted gold. Painter's marks, impressed marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 2847,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:24 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

Schwanenservice-Kuchenplatte, Henkelschale. Meissen. 1986, 1997. Modell-Nr. 5506, 5276. ø 29,5 cm, Breite: 33,5 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, gold staffiert. Malermarken, Pressmarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 2289,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:24 Uhr (CET)Swan service cake plate, handle bowl. Meissen. 1986, 1997. model no. 5506, 5276. ø 29.5 cm, width: 33.5 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, painted gold. Painter's marks, impressed marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 2289,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:24 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

2 Schwanenservice-Tassen, Untertassen. Meissen. 1986. Modell-Nr. 5584, 5585. ø 14-15 cm, Höhe: 5-9 cm. Modell von Johann Joachim Kaendler und Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. Die gesamte Oberfläche reliefiert, auf gewellten Muschelrippen Schwäne und Reiher, im Wasser Schilfstauden, Muscheln und Weinblätter. Dekor-Nr. 397152, farbige Bemalung mit indianischen Blumen, farbig und gold staffiert. Tassen mit Delphinhenkel. Pressmarken, Schwertermarken. Meissen-Manufaktur-Preis: 1498,- Euro * Partnerauktion Bergmann. Provenienz : Hessischer Privatnachlass. Aufrufzeit 28. | Feb. 2025 | voraussichtlich 13:26 Uhr (CET)2 swan service cups, saucers. Meissen. 1986. model no. 5584, 5585. ø 14-15 cm, height: 5-9 cm. Model by Johann Joachim Kaendler and Johann Friedrich Eberlein 1737-1741. The entire surface in relief, swans and herons on wavy shell ribs, reeds, shells and vine leaves in the water. Decor no. 397152, colored painting with Indian flowers, colored and gold painted. Cups with dolphin handles. Press marks, sword marks. Meissen manufactory price: 1498,- Euro * Partner auction Bergmann. Provenance : Hessian private estate. Call time 28 | Feb. 2025 | probably 13:26 (CET)*This is an automatically generated translation from German by deepl.com and only to be seen as an aid - not a legally binding declaration of lot properties. Please note that we can only guarantee for the correctness of description and condition as provided by the German description.

A dyed green chalcedony ring, with an oval dyed green chalcedony cabochon, claw set to a scalloped mount, into shoulders with incised scallop shells, upon a flat section shank, stamped 750, tested as approximately 18ct gold, 9.28g Ring size R½Buying this gemstone ring at auction could save up to 0.42 tonnes of CO2e compared to buying new. Condition ReportA little dirty. Would benefit from being cleaned. Minor marks and scratches to surfaces.

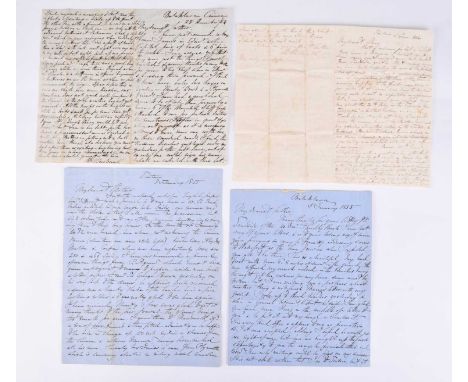

CRIMEAN WAR. Provost-Marshal William Donald MacDonald, 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot Four autograph letters signed to his mother, father, and sister, Mary, June 1854 - February 1855, written from Balaklava and Scutari, totalling 13 sides, some letters with multiple date entries. Sold with full typed transcripts for each letter. The letters offer firsthand accounts of military movements, daily life, and the realities of war during the early period of the Crimean campaign. Some excerpts include:Scutari and Varna, June 1854Macdonald's letter to his sister Mary begins with gratitude for correspondence from home and transitions into detailed accounts of military operations. He describes the combined British, French, and Turkish forces assembling near Varna, expressing optimism for their campaign: "What various rumours we hear daily respecting the war and the probabilities of peace... the combined army will present so respectable an appearance that I can almost fancy your reading some day about 20th July, in the Times, by Elec. Telegraph, important victory etc etc.” Remarking on daily activities, "I have now plenty to do, out riding about from 8am to 6pm only coming home to get another horse & passed by having to prosecute some natives before the Pasha or soldiers before their Col(onel): I am going to prosecute 5 natives today for being concerned in firing into our Artillery camp, one of them will certainly come to great (bastinadoed)" (foot whipped). He captures the volatile local atmosphere: "Everyone here is armed with guns, pistols & knives. I never go out without some sort of weapon & the inhabitants think nothing of human life." He praises the Turkish troops: “I saw some of these latter drilling yesterday & they made a very respectable appearance.”Macdonald details his personal circumstances, including his establishment of horses and staff: “On the whole though unlucky I am contented with my establishment which consists of self & 3 horses, an Interpreter & 2 servants.” Reflecting on his surroundings, he describes Varna: "Varna is a tolerable place for a town in Turkey, but still it is as bad as the meanest village in England."Scutari, February 1855 Addressed to his mother, this letter captures the grim realities of wartime mortality and hospital conditions. Macdonald contrasts traditional funerals with the harrowing scenes at Scutari: “50-60 dead bodies [are] huddled in one large hole daily, one service read over the whole & that is all.” He highlights the staggering death toll: “In the month of January 1482 were buried here alone, not reckoning the Crimea, Varna... Malta & Corfu where we have respectively 1000, 400, 250 & 460 sick.”The logistical challenges of managing the sick and wounded dominate his narrative: “The officers really available for work here are 6 in number which gives them plenty to do.” Despite the bleak conditions, he conveys a glimmer of optimism as he notes improvements: “An officer just come in from the Crimea has told me matters are greatly improved within the last few days so it is really to be hoped they will continue improving.”Balaklava, Crimea, December 1854 This letter, addressed to his father, showcases the campaign's challenging logistics and labour-intensive efforts. Macdonald describes the vast scale of labour: “300 Highlanders & 200 Marines 400 French troops are daily employed carrying 10-inch shells from this to the heights – 2 men to each shell & 500 Turks carry gabions, fascines, planking for guns to rest on & to build houses.”He recounts the strain between the British and French forces: “The French are very much annoyed with us at our shortcomings in the line of the Commissariat.” He also notes the anticipation of significant military action: "We are all expecting something great to come off about the New Year so many heavy guns & large shot & shell having gone up of late.” Macdonald offers personal insights, such as his remarks on Russian deserters under his command: “Out of 14 only one could sign his name, but all are contented with their lot.” Lastly, he reflects on his career prospects, hoping for recognition: “I am looking forward to when this is ended being made a Bt Major shd [should] I have performed my work satisfactorily.” Footnote: Lieutenant-Colonel William Donald Macdonald (b.1827, Scotland - d.1862, India) Footnote:Wiliam Donald Macdonald, born 15th September 1827. Married Emma Lindsay, 30th Augst 1860. His brother, Major Henry Macdonald, Bengal Infantry, was murdered at Fort Michni, 1873. Tablet it St. John's Church, Peshawar - "Sacred to the memory of Lt Colonel William Donald Macdonald of Sandside, Deputy Lieutenant and Justice of the peace of the county of Caithness, Scotland, who died of cholera while commanding the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders at Camp Jalozai on the 29th October 1862 aged 35 years. Macdonald served in the Crimea as Provost-Marshal, promoted to Brevet-Major on 25th December 1856. Deputy Assistant Adjutant General to the forces in China from 23rd March to 19th November 1857. Subsequently with the 93rd in the Indian Mutiny. Macdonald had the Crimean Medal with clasps for Alma, Balaklava, Inkermann and Sebastopol, Turkish Medal, 5th Class of the Medjidie and the Indian Medal with clasp for the capture of Lucknow.

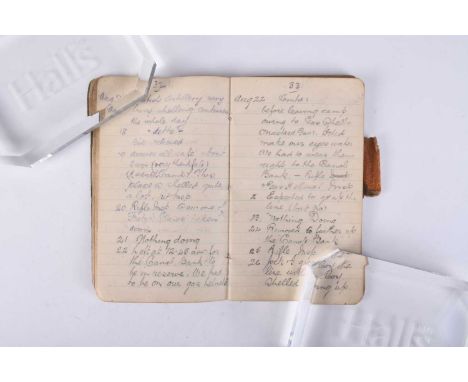

The First World War pocket diary of Private James McDonald, No.307558, 14th and 1/8th Royal Warwickshire Regiment. France and Italy, December 1916 to 12th July 1918. A compact diary measuring 3 x 5 inches, with 76 filled pages of daily entries documenting Private McDonald’s service during WW1. The diary includes detailed accounts of his training, movements, experiences in the trenches, and encounters on the Western and Italian fronts. Sold together with a full typed transcription. Notable Entries:24th December 1916: "Left Chiseldon for France on the 24th Dec 1916 - Marched to Chiseldon Stn accomp(anied) by Brass & Flute bands. They played Gren(adier) Guards, Tipp(errary), The Girl I Left Behind Me and as the train went off they played 'The Swanee River' & Auld Lang Syne. Arrived in S(ou)th Hampton at 11.320am. Left ditto at 8.15pm with the transport ship H.M.S Victoria."1st February 1917: "Issued with 3 bombs. 50 rounds amm(unition). Ready to proceed up the line taking over the French position. Left at 4pm arrived at 8pm Peronne District. Support trenches. Western Front Gas Guard."4th February 1917: "Painful duty of burying the dead. Very bad night of shells, snipers, a hot time. Out from 1am coming back we lost our way, had to wait in a dugout until morning, unsafe to go out."18th March 1917: "Arrived at Halle 2am. Patrol duty the whole night. No sleep very tired. The Germans evacuate. Marched on to Maimont then Peronne (City). The last Germans must have left this city time ago. No sign of any Boches. Was one shot coming through the city. What a city of destruction, burning b(ui)ld(ing)s a sad sight. (On sentry). Bridges blown up. Was brought across the canal on ponte (RE). The wells poisoned with arsenic (lovely day)."16th August 1917: "Left between 4am-5am marched to Canal Bank had breakfast there. What a quantity of batteries we saw on our road up. Left Canal Bank 7.15am. Excitement commences. Passed through a heavy barrage of fire shells dropping quite close to us. Had to change our route shell drops right by our side. Got a shower bath it landing in a hole full of water. Met a lot of British & German soldiers coming down the line. Got into a trench where we were sniped at a great deal, two chaps gets wounded in this trench."22nd August 1917: "Left at 12.45am for the Canal Bank to be in reserve. We had to (put) on our gas helmets before leaving camp owing to gas shells (Mustard Gas). It did make our eyes water."1st November 1917 - 15th December 1917: A sequence of entries detailing McDonald's admission to hospital, confinement to bed, and recovery before returning to duty.6th January 1918: "Arrived at San Remo. Stopped there for a short time ... Italian ladies & gentlemen gave us cigs, matches & (?) there, arrived at Aquatic. All along the way the Italians gave us a grand reception."27th April 1918: "Out on a forward position from 5am to 8pm. One of our Company's made a stunt. 1 prisoner taken. What a night of rain. Slpt through the bombard(ment). Never heard it." Condition:Binding is secure but the covers are dog eared with a fold to the front top right and a damp stain to the lower left, alongside losses to spine - please see photos

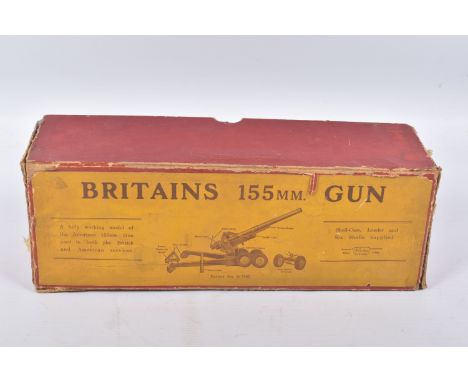

A BOXED BRITAINS 155mm GUN, No.2064, appears complete, playworn condition with some paint loss and wear, missing shells and shell case loader, but complete with instructions, catalogue leaflets, order form/price list and complaint slip, box complete with packing pieces but has damage, marking and wear

A rare, and possibly unique combination of medals, including the rare King’s Police Medal for Gallantry, issued to Herbert Adams for service in the Royal Navy, H.M. Coastguard, and the Wear River Police. To include: the China War Medal of 1900, issued for service during Boxer Rebellion, named to ‘H.Adams LG.Sea H.M.S. Peacock’, with impressed naming.Together with an Edward VII issued Naval Long Service & Good Conduct Medal, named to ‘147035 Herbert Adams. Boatn. H.M.Coastguard’ (impressed naming), and a cased King’s Police Medal with the distinctive ribbon denoting that it was issued for gallantry, named to ‘Herbert Adams. Const. River Wear Police’ (engraved naming).Also included is a period photograph of Herbert, wearing the uniform of the River Police, with his collar number of 22 clearly visible, and all three of his medals.Plus, his early 20th century nickel Bosun’s whistle and chain, which has a manufacturers mark that appears to be Chinese in origin, a pin on ribbon bar, three period service documents, and a newspaper clipping announcing the death of Herbert, and some details surrounding the award of his King’s Police Medal.Notes: Herbert Adams was born in 1873, in Stoke Fleming, Devon.He first volunteered for service upon HMS Impregnable on November 5th 1888.His certificate of service states that he was a baker at the time of his attestation, and resided at Crowthers Hill in Dartmouth.Herbert served on numerous vessels during his naval career, and served on HMS Peacock from October 1897 through to June 1901, which covered the Boxer Rebellion period. Herbert was awarded his Long Service & Good Conduct Medal in November 1904, by which time has was serving on H.M. Coastguard ship ‘Dido’ the shore establishment HMS President, and the Haven Hole coastguard station at Canvey Island.Following on from his 21 year career in the Navy, Herbert then served a further 20 years with the ‘River Wear Watch’ (Police), during which his gallant conduct was rewarded with the award of his KPM.The London Gazette entry for the award is dated January 1st 1920, but the incident occurred in 1918 during WW1.Herbert, along with four other colleagues from the Wear River Police boarded the steamer vessel Hornsey, which was ablaze on the River Wear.The Hornsey was carrying around 700 shells, likely bound for the war effort, and the five police officers managed to extinguish the fire, despite the imminent danger from a catastrophic explosion.The King’s Police Medal is one of only 350 issued for Gallantry during the reign of George V. Condition: good. Some normal age related toning to the medals, and a little polishing to the high points of the design. A few very dents to the bosun’s whistle, plus some kinks to the chain. The leather case for the KPM is in very good and clean condition, with a working catch and hinge. The documents remain in good order, with just normal age and service wear.