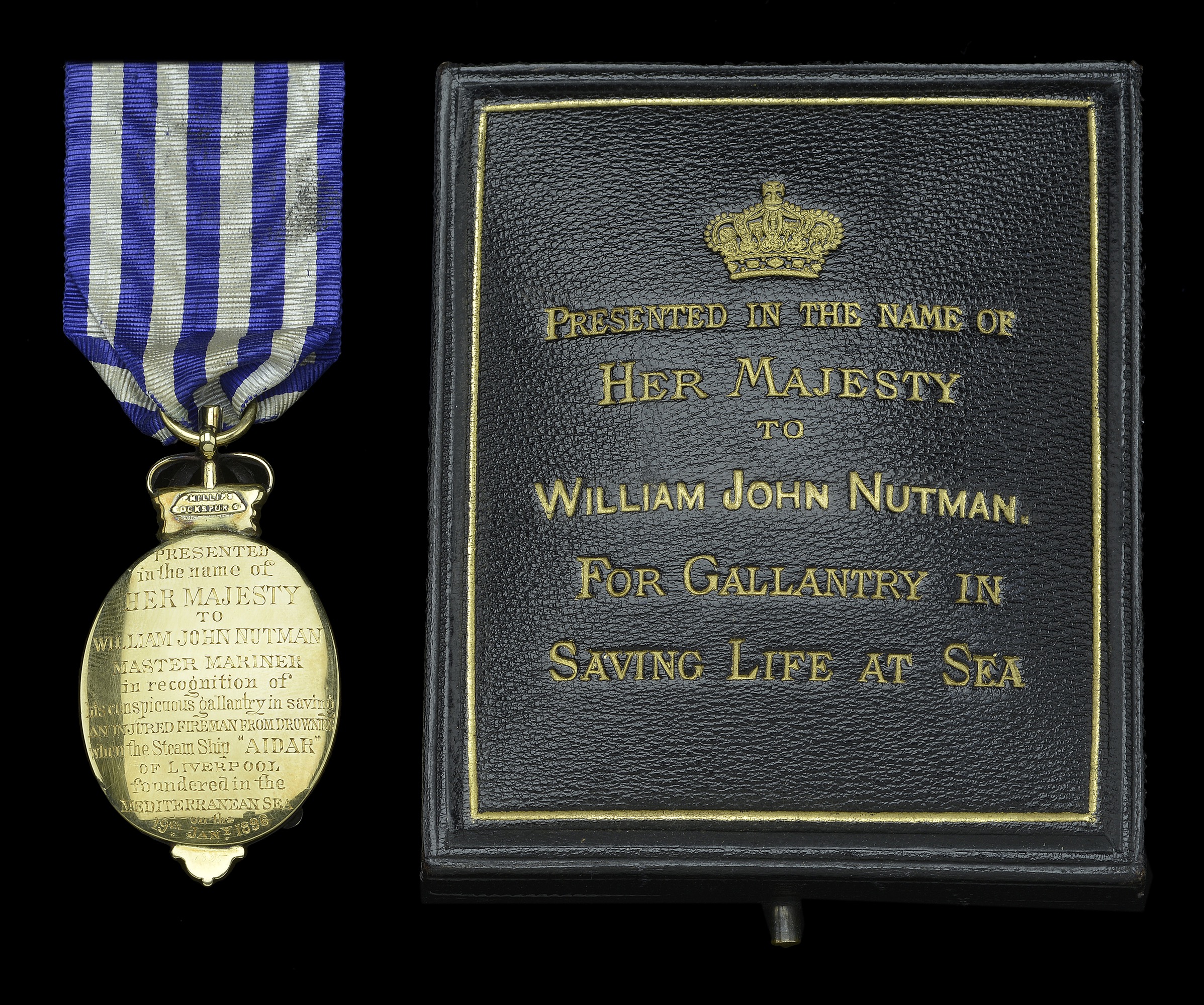

The remarkable and unique Albert Medal in Gold for Sea life-saving group of seven awarded to Mr. W. J. Nutman, Captain of the S.S. Aidar, for his great gallantry in saving the life of an injured crewman during a storm in the Mediterranean Sea on the night of 19 January 1896- with the rest of his crew saved he refused to leave the injured fireman behind, waving away the lifeboats as his ship foundered, ‘choosing to face almost certain death than to leave him behind’- an extraordinary group for an outstanding act of valour Albert Medal, 1st Class, for Gallantry in Saving Life at Sea, gold and enamel, the reverse officially engraved ‘Presented in the name of Her Majesty to William John Nutman, Master Mariner in recognition of his Conspicuous Gallantry in saving an injured fireman from drowning when the steamship “Aidar” of Liverpool foundered in the Mediterranean Sea’ on the 19th. Jany. 1896’, reverse of the crown with maker’s cartouché Phillips, Cockspur St., unnumbered, but with workshop number, in embossed leather case of issue; Royal Humane Society, small silver medal (successful) (William Nutman. 19th. Jan. 1896.) with top silver riband buckle, in case of issue; Lloyd’s Medal for Saving Life at Sea, large silver medal (Capt. W. Nutman. S.S. “Aidar” 19 January 1896) in case of issue; Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society Marine Medal, 3rd type, gold (Captain William Nutman for Gallantry and Heroism in saving life from wreck of S.S. “Aidar” 19/1/96) with top gold riband buckle, in fitted case of issue; Shipwrecked Fishermen and Mariners Royal Benevolent Society Medal, gold (Captain W. J. Nutman, S.S. Aidar, 19th. Jan: 1896.) with double dolphin suspension and top gold riband buckle, in case of issue; Mercantile Marine Service Association Medal, silver, the reverse engraved ‘To Captain William Nutman (M.M.S.A.) S.S. “Aidar” for gallant and heroic conduct in saving the life of an injured seaman after the foundering of his vessel Jan. 19. 1896.’, with top silver riband buckle, in case of issue; Merchant Service Guild Cross, 39mm, silver, silver-gilt, and enamel, the reverse engraved ‘Presented by The Merchant Service Guild to Capt. W. J. Nutman for Heroism at Sea April 1896’, with top suspension bar, in case of issue, suspension bar sprung on one side on last, otherwise extremely fine and better (7) £14,000-£18,000 --- A.M. London Gazette 14 April 1896: ‘At 2 a.m. on the 19th January 1896, while the S.S. Staffordshire, of Liverpool, was on a voyage from Marseilles to Port Said, signals of distress were observed to be proceeding from the S.S. Aidar, also of Liverpool, and the Staffordshire immediately proceeded to her assistance. As the Aidar was found to be sinking fast, three of the Staffordshire’s lifeboats were at once launched, and with great difficulty, owing to the darkness and the heavy sea, succeeded in rescuing her passengers and crew, 29 in number. At 6:10 a.m. the only persons left on the Aidar were Mr. Nutman (the Master), and an injured and helpless fireman, whom he was endeavouring to save, and whom he absolutely refused to abandon. The steamer was now rapidly settling down, and as it was no longer safe to remain near her, the Officer in charge of the rescuing boat asked Mr. Nutman for a final answer. He still persisted in remaining with the injured man, choosing rather to face almost certain death than to leave him to his fate. The men in the boat were obliged to pull away, and immediately afterwards, at 6:17 a.m., the Aidar gave one or two lurches and foundered. After she disappeared, Mr. Nutman was seen on the bottom of an upturned boat, still holding the fireman. Half an hour elapsed before the rescuing boat could approach, but eventually Mr. Nutman and the fireman were picked up and taken on board the Staffordshire, where the injured man was with difficulty restored by the ship’s surgeon.’ William John Nutman was the Captain of the 2,400-ton cargo ship the Aidar, which foundered in a northerly gale in the Mediterranean Sea. A fuller account of his great act of gallantry was published in The Strand Magazine: ‘At 2 a.m. on the 19th of January, while the steamship Staffordshire, of Liverpool, was on a voyage from Marseilles to Port Said, signals of distress were observed from the Aidar, and the Staffordshire immediately went to her assistance. The Aidar, it appeared, was on her way from Odessa to Marseilles, and the wreck occurred in the Mediterranean, near Messina. As the Aidar was found to be sinking fast, three of the Staffordshire’s life-boats were at once launched. But their crews experienced immense difficulty in the work of saving life owing to the darkness and the heavy sea. Three times was the Staffordshire manœuvred round to windward, and each time the life-boat was dispatched the rescuing crew were in serious peril of their won lives. During one visit, the boat was badly damaged by one of Aidar’s davits, which was just above the water. At 6.10 a.m. the only persons left on the wreck were Captain Nutman and an injured and helpless fireman, whom he was endeavouring to save, and whom he absolutely refused to abandon. The steamer was now rapidly settling down, and as it was no longer safe to remain near her, the officer in charge of the rescuing party from the Staffordshire asked Nutman for a final answer- would he leave his helpless charge and save himself? He would not; he persisted in remaining with the injured man, choosing almost certain death rather than leave him to his fate. Even the passengers tried hard to induce the captain to come away, but he would not. The fireman seemed powerless and paralyzed with fear, making no effort to save himself beyond clinging to the broken bridge, then down in the water, as the vessel was on her beam ends. As the Staffordshire’s life-boat returned each time, captain Nutman would say: “Pull away with those people and come back for me afterwards.” It is necessary to explain that the boat could not come quite close to the sinking ship, simply because no one knew the moment when the latter might founder and suck down with her anything that chanced to be floating in the vicinity; moreover, there was a terrific sea. At last, after having given Captain Nutman many chances of life, the men in the rescuing boats were obliged to pull away reluctantly, and immediately afterwards, at 6:17 a.m., the Aidar gave one or two heavy lurches and then foundered. Long after this the Staffordshire’s life-boat returned to the spot, it crew perhaps animated by vague hopes, and the officer commanding it was amazed to behold Captain Nutman clinging to the bottom of an upturned boat, still grasping the now unconscious fireman. Another half-hour elapsed before the boat could approach, but eventually this hero and his precious charge were picked up and taken on board the Staffordshire. In all 24 persons were saved, one only, a boy, being drowned. This was the cabin boy, who was washed over-board during the night and not seen after 12:30 a.m. Colonel Sir Vivian Majendie, the well-known explosives expert at the Home Office, interested himself very much in this case, and obtained a number of facts about it. He had a conversation with Captain Nutman himself, who came from Port Said in the same ship with him. Sir Vivian gathered that the fireman was much too injured to make any effort to save himself, and if left by Captain Nutman he must have inevitably perished. There was also a German passenger on board the Aidar who was so paralyzed with horror at the aspect of things that he could not be persuaded to jump from the ship into one of the rescuing boats; and he, too, must have been lost had not Captain Nutman, with great determination, taken...