We found 14614 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 14614 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

A pair of Royal Crown Derby plates, decorated in underglazed blue with fanciful birds, printed mark, date code for 1906; a Victorian plate, painted with two children by Corrie Robinson, dated 1883; another; Spode Ironstone plates; other Victorian and later plates; Royal Devon biscuit barrel; etc

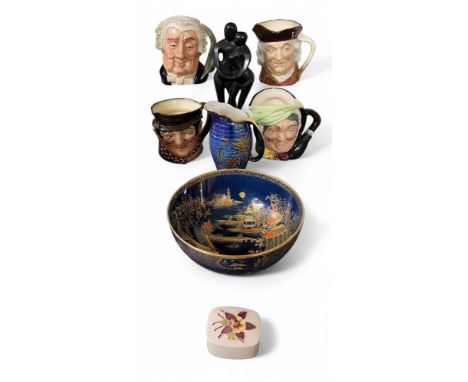

Manner of Henry Moore, carved granite sculpture 'Embrace', 32cm highl Royal Doulton character jugs, Sairey Gamp, D528; The Lawyer, D6498; Sam Johnson; Sam Weller; Moorcroft trinket box and cover; Carlton Ware Chinoiserie pattern bowl, printed and painted in colours and gilt with pagodas and figures, 23cm diam, printed mark, 2519; a Crown Devon ribbed jug, transfer printed with fish and fronds on a blue lustre ground, 19cm high, 3143

Ceramics - a Wedgwood Devon Sprays pattern part dinner service, comprising serving platters, tureens, dinner plates, dessert bowls, dessert plates, side plates, sauce boat and stand; a Royal Crown Derby paperweight, Pig, moulded stopper, second quality; Posies trinket dishes, etc; Coalport, etc, qty

A GROUP OF MISCELLANEOUS CERAMICS, comprising, two Goebel West Germany figures of a gentleman, makers mark on the base, model no. 16 026-21 also known as Bochmann, (a nibble on the hat), a Gerhard Bachmann lady with a fan, makers mark on the base, model no. 16 025-21, children's dinnerware including a vintage Royal Falcon Ironstone dinner plate, side plate and bowl, featuring a girl with ducks and dog motif, others include Old Foley James Kent, three plates from the nursery rhyme series, etc. a selection of animal figures cats, dogs, horses, etc. names include Beswick, Nao, Cooper Craft, etc. a group of studio pottery small vases, jugs, plate, large vase, etc. an R. White ginger beer bottle in stoneware, (no stopper), vintage Crown Devon vase no. 1094, Delhi water jug with pewter lid T. Booth stamped in the underside of the lid, a Holt Howard cat string holder, Simonelli Depose Italy girl figurine 436, oriental carved monkey soap stone inkwell/brush pot, etc. (qty), (Condition Report: all items appear in ok condition some have slight nibbles and wear)

Five decorative wall plates, comprising a near pair of 19th century Imari pattern porcelain chargers, diameter 31cm, an Art Deco Crown Devon charger, with tree branch decoration in a descending ring texture, a charger with green leaf pattern, diameter 30cm, height 4cm, a Royal Winton charger, with Art Deco stylised landscape scene to the centre and a moulded green border, diameter 31.5cm, and a Royal Doulton large plate, with repeating swags of colourful garden flowers, diameter 25cm (5).

Pair of Crown Devon Fieldings 'Dragon' lustre vases of ovoid form, decorated with colourful polychrome enamels, with gilt rim, on a blue ground, pattern no. 2069, approximately 23cm high. (2)CONDITION REPORT: No obvious chips to the rims when feeling with a finger. Slightly raised area below one rim. Looking through a glass we can see minor losses to the gilt on the rim, raised blacked mark to the rim also, could be a stain but not convinced its a restoration mark. Again some fairly minor losses to the enamel, mainly to the purple and gilt. Good detail to the exterior. Generally good detail to the dragons, with minor losses present. The raised stones appear to be in good condition. Very minor crackling to the glaze/enamels. Losses to the glaze on the underside with some crazing also to the underside.

A GROUP OF DECORATIVE CERAMICS, comprising six Shorter & Son shell shaped vases, in various shapes and sizes, most in a pale green, one pink and a pale yellow colour, a Crown Devon gilt leaf bowl, Sylvac item include, wall pocket in the shape of a shell, 1395, small vase, 684, lustre feather salad dish and tray, 3507, etc. also included a Wade and Beswick basket shaped posy bowl, a double Beswick candle holder, jug shaped vase 98-1, two pieces of Falcon Ware a bud vase and dog figure outside his kennel etc.(qty), (Condition Report: all items appear ok with no obvious damage, there is signs of crazing on some items)